When I became the recorder for Racine County, Wisconsin, in 2011, I envisioned sharing records and parcel data with the public using focused web apps. I wanted a lean, efficient government enabled by modern mobile and web technology.

I knew this would be a challenge—more than a decade had passed since the county’s first GIS implementation. In the intervening years, advances in web GIS had outpaced the county’s ability to keep up with changes in technology. Our GIS consisted of a legacy map viewer with multidirectional arrows that users had to click to navigate. It had too many layer options, expressed stale data, and was slow. What was a first-of-its-kind public-facing mapping system in 2006 had become a relic.

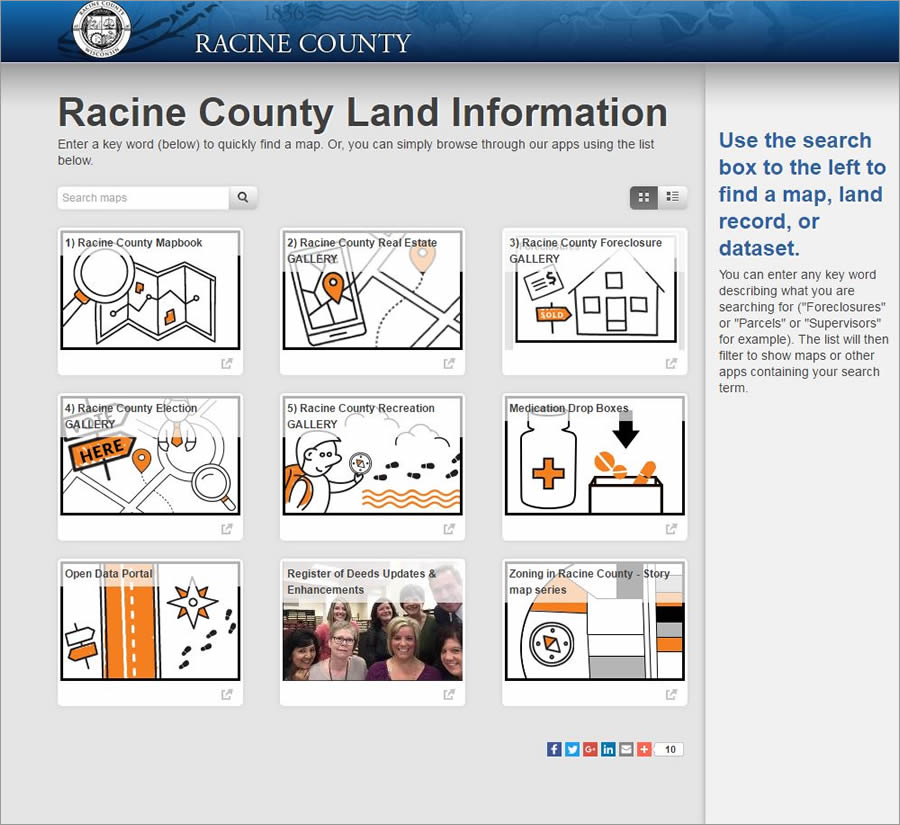

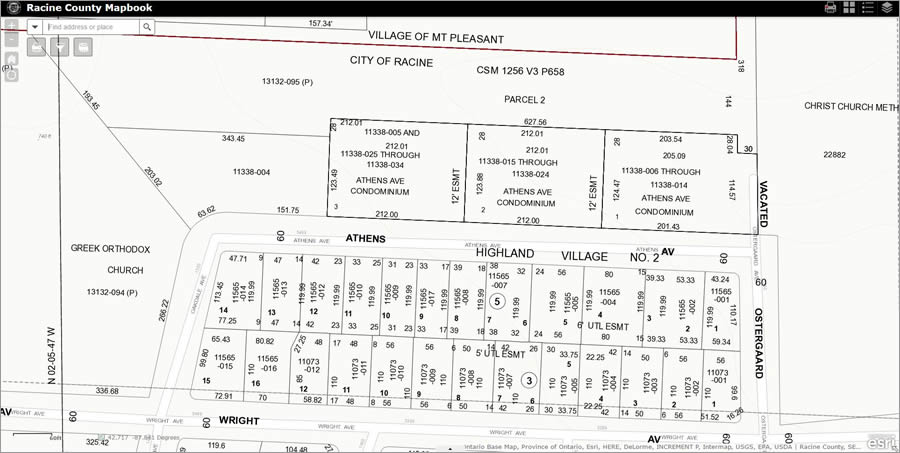

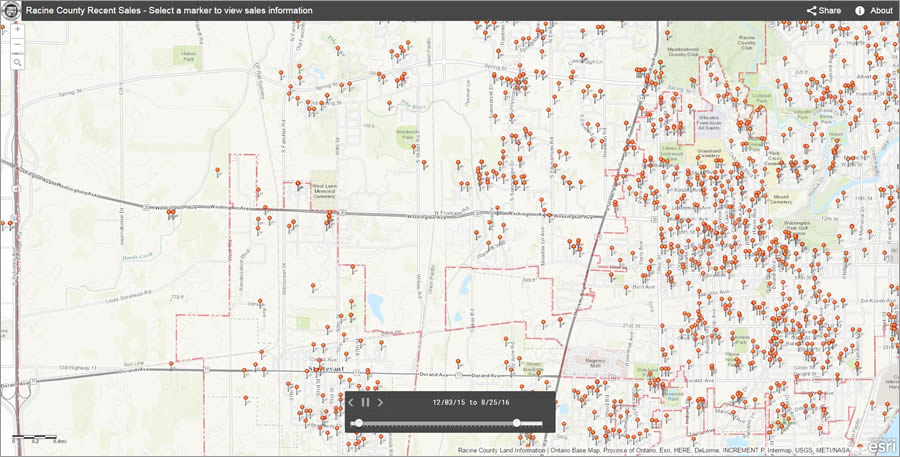

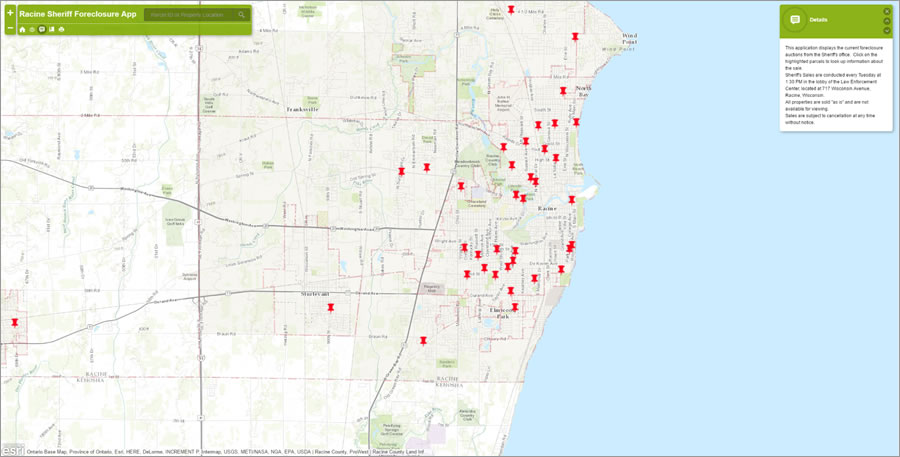

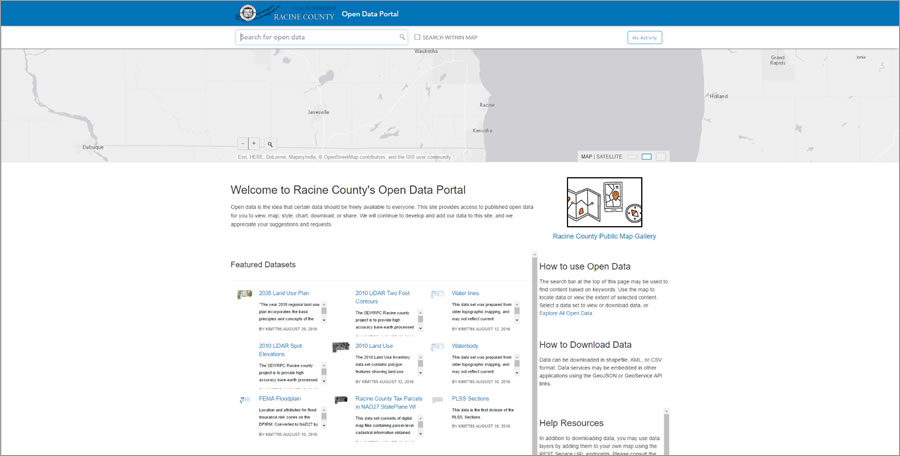

Today, the county Register of Deeds apps and an open data portal appear in a portfolio on the GIS & Mapssection of the Racine County home page. Created with web GIS templates available in Esri ArcGIS Online the apps in the gallery give our community immediate access to land, property, and tax information that residents previously could only obtain by visiting or calling the Register of Deeds office. Web GIS now lets us serve essential land information to residents in the form of apps such as Racine County Mapbook, which displays parcel ID numbers, names of landowners, and current assessment values; Racine County Recent Sales, which maps the location of property sales; and the Racine Sheriff Foreclosure App, which lists dates of sales for foreclosed properties. The portfolio page also includes a multipurpose portal that hosts a growing collection of more than 20 land-related datasets that people can download or map within the same interface.

How did we get to the point where Racine County residents can now easily map open data and find many land records documents online? From 2011 and 2015, we scanned old records, updated our aging tax system software, and connected real estate data in the county to lay the foundation that would make my vision a reality. We have achieved this goal by using the ArcGIS Online Web GIS resources available through Racine County’s license agreement with Esri.

Weeks after the Register of Deeds office launched the project in 2015, the county board noticed our progress in connecting major systems and subsequently green-lighted integration for the whole enterprise.

Integrate and Deploy

Our public-facing mapping system also needed to be usable on mobile devices. If you wanted to view the maps on an iPhone or Android device back in 2011, forget about it. More than half of all citizens and workers today access maps on phones and tablets—mobile capability was becoming an expected public service for the county. Without standardization and a vehicle to nimbly share county land records data, none of the office’s digital assets would be in any shape for presentation in mobile browsers, much less desktop browsers.

To modernize the county’s information data management and serving practices, my office collaborated with Esri partner Pro-West & Associates, which helped us define two broad objectives for the overhaul:

- Integrate the processes of multiple departments.

- Deploy solutions quickly that work on any mobile client.

To my surprise, I learned that the Local Government Information Model (LGIM), Esri’s standard for homogenizing all local government data holdings, would help us meet the first of those objectives. LGIM essentially converted all office data into the same language so that all systems could “talk” to each other. This meant that data in the tax system could be hyperlinked to the specific item on the map and vice versa; items on the maps can be clicked, which takes the user back to the tax system and creates a continuous fact-finding experience.

To deploy solutions quickly, the county used Esri’s web app templates configured for common government tasks. Esri provides easily modifiable land record templates to serve tax parcel information and show the location of all foreclosed properties within any county. Migrating to LGIM was the first step in getting the data uniform and connecting departments, enabling us to produce public apps quickly.

A significant part of that process involves migrating parcel data to the parcel fabric—Esri’s parcel editing standard and a subset of the LGIM standard that contains necessary data layers. With so many departments—including police and fire—relying on the office’s parcel maps for accurate addressing, the fabric would establish a clean address database for our county as well as bring semiautomated editing to parcel work.

Pro-West helped assess our data and create an action plan that included a fundamental data cleanup. This involved using rules to move data to LGIM and prepare it for migration into the parcel fabric.

Presenting the Apps

One of the first web apps to populate the gallery was Racine Sheriff Foreclosure App. For years, the Racine County Sheriff’s Department had compiled a list of foreclosed properties and posted it in public places like the library and Town Hall. To readily present that information to a wider audience, we collaborated with the department to create a map that displayed information from the county foreclosure database. Users can click on properties and get the parcel ID and other information, such as time and date of sale.

Soon after that app went online, we launched Racine County Recent Sales. The list of weekly home sales in a county like ours usually appears in a newspaper. The app includes a time slider for users to animate the chronology of recent sale properties and see a wealth of weekly updated property sales data. Each pin links directly to the tax system and expresses the data in it. Clicking the pin opens a pop-up window that shows assessed value, tax amount, and other registry information—a huge improvement over the newspaper’s static list.

The latest addition to the gallery is our new Open Data Portal. Although not specifically land records related (it includes everything from imagery to soils data), the portal will eventually be expanded and folded into our county enterprise GIS.

Follow the Model

While the gallery includes many apps, the Racine Sheriff Foreclosure and Racine County Recent Sales apps exemplify what is so appealing about LGIM. First, the model simplifies the work of homogenization by getting everything standardized and connected. That’s essentially part one. The second part is apps that give all that hard-fought extraction, transformation, and loading (ETL) work—the scanning, the data scrubbing, the converting—an avenue of expression that’s accessible anywhere. I also can’t overemphasize how appealing it is that these apps work on all devices, given the obvious mobile nature of land records management.

Admittedly, the first step of digitizing/ETL is the biggest in terms of effort but bears the most fruit down the line. That rigorous back-end work is what ultimately removed more than 20 steps from the legacy process of getting land records and property tax data to users on the front end. Now Racine County is poised to create more apps this way for many of its offices using its Register of Deeds office as a guide.