As Negative Health Effects from Climate Change Grow, Sophisticated Technology Will Guide Preparation

The earth’s climate is changing, and this will have a tremendous impact on human health. But the relationship between climate change and health is complex.

Ongoing climate change observations and associated prediction models show clear evidence that significant portions of the American population are experiencing various health-related repercussions. Yet the relationship between climate change and human health has not been widely recognized as a major public policy issue, which means that very little practical attention has been paid to the massive public health costs associated with existing and future climate change.

Gaining a better understanding of the interconnections between climate change and human health requires substantial investment in scientific monitoring, risk mitigation, and devising resiliency strategies. One sophisticated technology that can be employed to carry out these daunting tasks is GIS. With its remarkable capacity to distill complicated issues into straightforward, visual representations, GIS will be crucial to guiding interdisciplinary approaches to prepare for the public health impacts of climate change and formulate resilient public health plans.

How Climate Change Affects Health

General scientific consensus clusters most of the effects from climate change into four major categories:

- Increasing intensity, duration, and frequency of extreme weather events

- Rising temperatures both with and without elevated precipitation

- Increasing levels of carbon dioxide

- Rising sea levels accompanied by an escalation in coastal flooding and erosion

For each of these major climate change categories, a number of specific health effects are already being observed across large tracts of the United States. More disturbingly, many of these climate-health impacts are occurring faster than forecast over the last 20 years and clearly fall outside ranges of historical variability.

Regarding rising temperatures, many American cities and states are experiencing escalating air pollution, which is resulting in increased rates of asthma and cardiovascular disease. When temperatures rise and precipitation doesn’t, this leads to intensified desiccation, prolonged extreme drought conditions, and higher levels of particulate matter that is equal to or less than 10 and 2.5 micrometers in diameter (called PM10 and PM2.5, respectively), meaning it can get into the lungs. All these conditions are leading contributors to respiratory illnesses, including emphysema and, potentially, lung cancer.

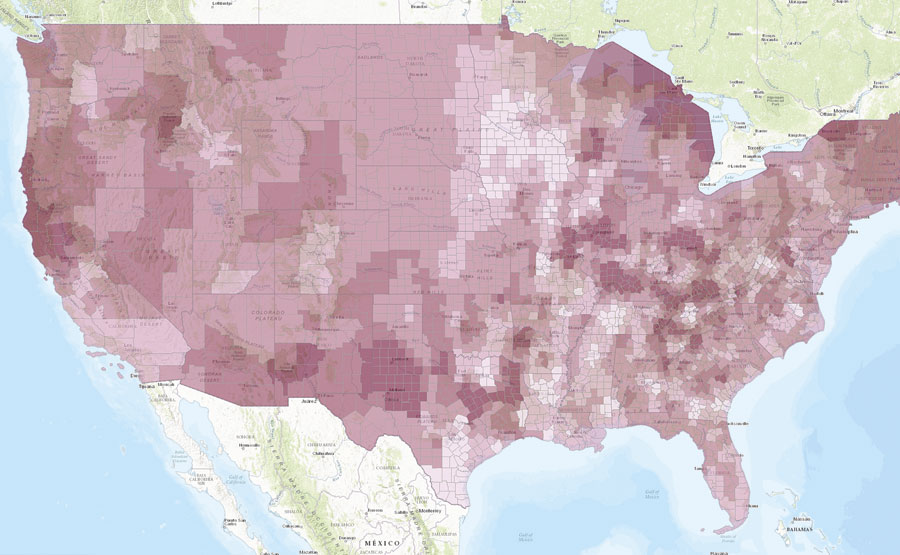

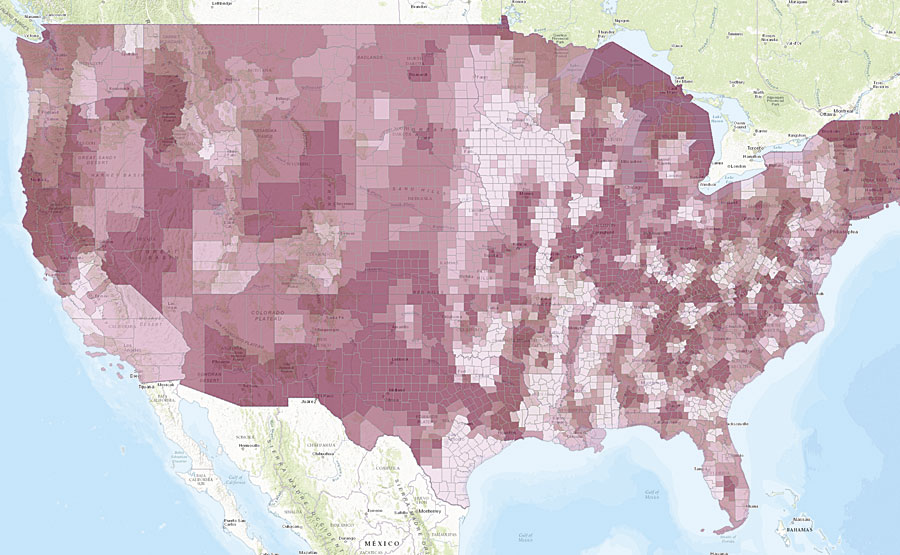

The Navigator Transformation app, developed by Upstream Research, Inc., shows current (left) and future (right) rates of adult asthma for every county in the United States. Various climate change-related phenomena, such as increases in PM2.5 and PM10, will contribute to future spikes in asthma.

Meteorologically, rare weather events—often called 500- and 1,000-year storms—are surpassing their event cycles on an annual basis. These changes in extreme weather patterns, combined with increasing annual temperatures and rising sea levels, are causing shifts in vector ecology as well, which affects how diseases are transmitted to human populations. With more instances accruing of malaria, dengue fever, encephalitis, hantavirus, Rift Valley fever, Lyme disease, chikungunya virus, West Nile virus, and now Zika, we have not yet figured out how to manage these diffusing diseases.

Rising sea levels plus an increase in significant flooding events are already impairing surface and subsurface water quality. Waterborne illnesses—including cholera, cryptosporidiosis, campylobacter, leptospirosis, and various ailments caused by toxic algae blooms—are on the rise in many regions of the United States.

Changes in water quality also exacerbate the availability of fresh water in places with depleted or difficult-to-access reserves, such as Los Angeles, Houston, Salt Lake City, and Miami. California’s Central Valley is currently suffering from its worst drought in more than 1,000 years. Given that this area yields about two-thirds of the United States’ fruits and vegetables, the lack of fresh water in the region is having complex effects on food supplies.

Globally, these problems have reached epidemic levels and are only increasing among urban populations. Breakdowns in essential services, such as education and trash collection, go hand-in-hand with environmental degradation and can lead to civil conflict, population migration, and significant mental health challenges.

Although Americans tend to observe these occurrences from afar, there is evidence that these impacts are affecting the United States as well. Populations of extremely low socioeconomic status are already at risk for serious health problems, and climate change is increasing the likelihood that they will get sick.

A public health crisis of epic proportions is looming, and we are largely unprepared.

Using GIS for Public Health Resiliency Planning

The challenge now is to develop innovative, cost-effective tools that allow public and clinical health officials to combine complex climate change modeling with epidemiologic, econometric, and demographic analyses in a way that supports sound policies and sensible decision-making.

GIS is currently being used to combine meteorological, climatological, demographic, and ecological information into various models used for risk assessment, forecasting, and resiliency planning. Instead of wading through exhaustive reports and studies, stakeholders can see—on a map—how increasing temperatures and decreasing precipitation, for example, exacerbate wildland fires and give way to increasing risk from illnesses such as coronary artery disease.

GIS makes spatial correlations clear so that health care organizations can perceive the direct negative impacts of climate change on local and regional areas. With the Zika virus, for example, real-time GIS is being used to model changes in vector ecology for this emerging infectious disease. Maps show how, as temperature, precipitation, and human ecology adjust to a changing climate differently at specific latitudes and longitudes, mosquitoes extend their habitats, making mosquito-borne viruses like Zika more prevalent throughout the world.

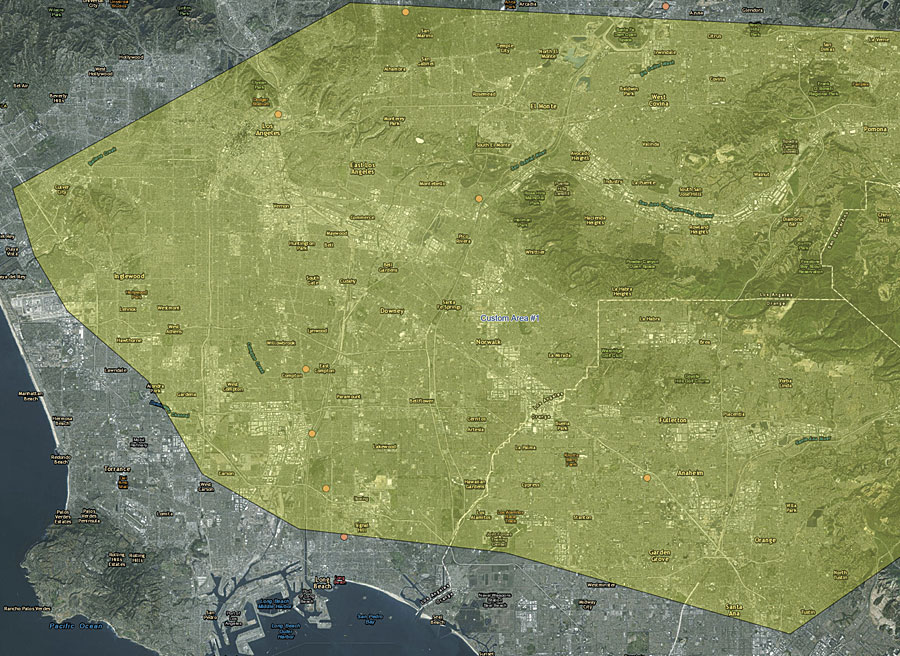

Using GIS can also clearly demonstrate the public health costs associated with climate change. A map of Los Angeles that combines demographic, epidemiologic, and econometric data can gauge the prevalence of various diseases in the area—including chronic lung disease, which is estimated to cost $349 million to treat annually in and around Los Angeles. Climate change models of the Los Angeles basin over the next 10 years show that temperatures will likely increase while precipitation decreases, causing elevated levels of PM2.5 in the area. This will exacerbate certain respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, including chronic lung disease. While it is difficult to isolate climate change’s precise impact on respiratory diseases (though scientists are trying), it is estimated that the number of asthma cases in the Los Angeles basin will increase by approximately 164,000 between 2016 and 2025, which will place a significant additional burden on health care systems.

Geographers at the Helm of Progress

At a time when federal, state, and private funding for health care in the United States is decreasing, such detailed information on climate-related health changes is sorely needed. And it is geographers who have the ability to quantitatively and qualitatively measure these effects over time.

With GIS, it is possible to understand the impacts of climate on human health, forecast specific ramifications, and develop algorithms that leverage the earth’s finite resources to come up with feasible resiliency plans.

In the next 10 years, the impacts of climate change on human health will become increasingly pronounced and acute. Preparing proactively now—using GIS as a guide—will result in substantial cost savings, drastic reductions in disease, and decreased human suffering.

It is crucial that geographers get started now.

About the Author

Alex Philp, PhD, is the founder and chief science officer of Upstream Research, Inc., an emerging Esri partner that focuses on using advanced analytics to prevent disease in human populations.