About the author: Mark Gallant is a geographer and GIS professional from Ottawa, Canada. Before joining Esri Canada as a Senior Consultant, he spent 12 years at the National Capital Commission where he leveraged ArcGIS Online technology to help tell the story of Canada’s Capital. Outside of work hours he creates story maps covering topics not normally found within the traditional scope of geography for his non-profit website EntertainMaps.com.

_______________

One of the best ways to learn the ins and outs of good story mapping is to tackle a topic that you find interesting on a personal level. Whether you’re a student building your knowledge base or a seasoned GIS professional who might be new to story maps, creating something that you genuinely hold an interest in will motivate you to get things right.

If you’re struggling to find a topic that inspires you, look at something you enjoy as a hobby or as a spectator and focus on its ties to location. This might be the away schedule of your favorite sports team, the studios of where your favorite music albums were recorded, or a vacation destination that means something special to you. Try to pick something that works well as a narrative or that can act as a spatial inventory of events.

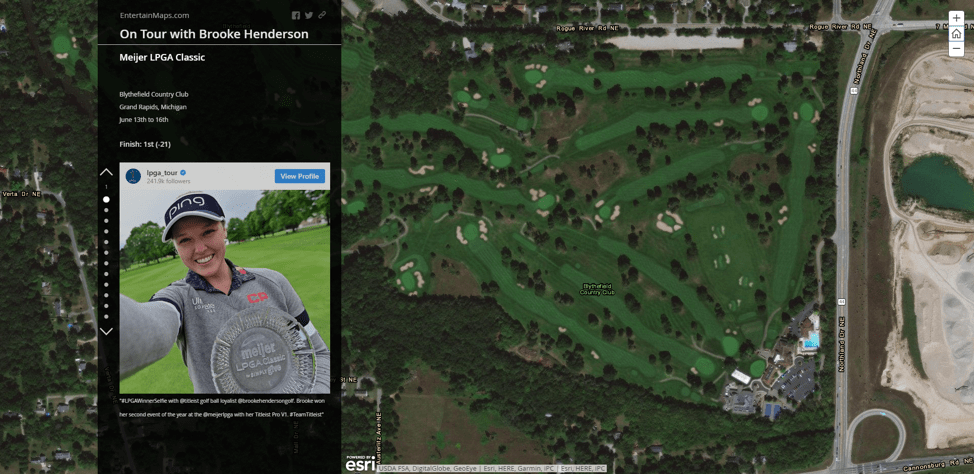

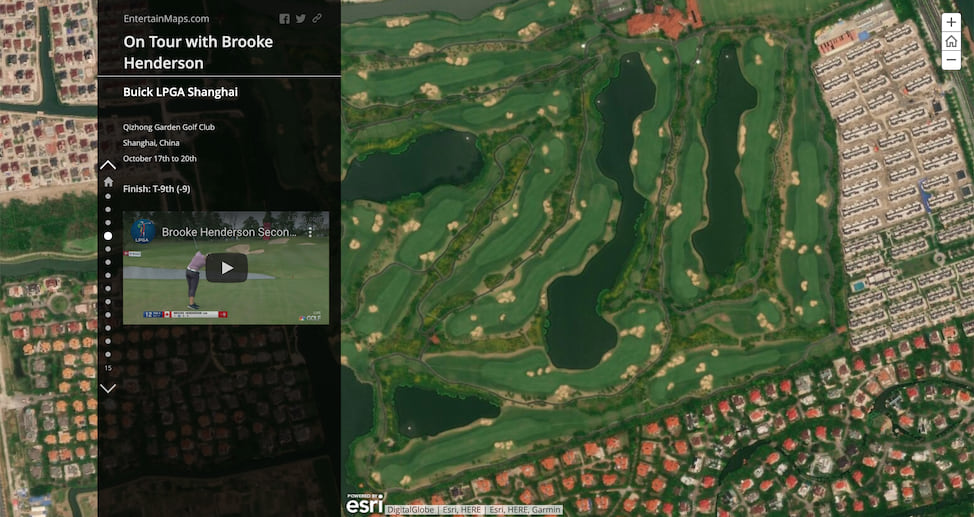

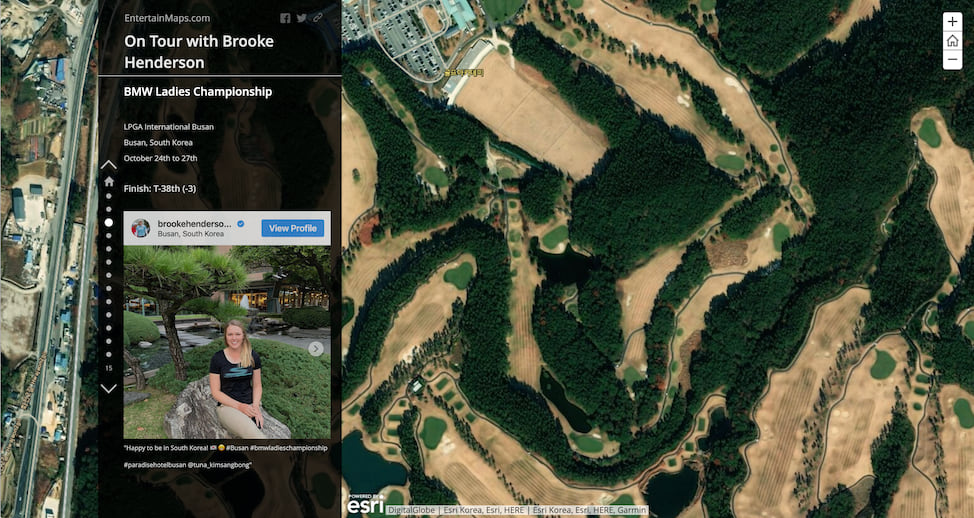

On Tour with Brooke Henderson

Here’s an example: I followed the 2019 LPGA Tour season of Brooke Henderson, who began the season two wins away from becoming the winningest Canadian professional golfer of all-time. I wanted to (hopefully) capture these next two wins in a Story Map Journal that documented each tournament Brooke played in with an aerial map of the course, her score, and any highlights or snapshots of her rounds that might be publicly available via the official LPGA Tour YouTube page or Instagram feed.

Brooke ended up securing those two wins this season and is now the winningest Canadian professional golfer of all-time.

The process of having to regularly update my Map Journal after each tournament with a new map, new text and a new social media embed kept my story editing skills sharp and allowed me to develop a small workflow of pulling in the required information quickly and efficiently (especially if I wanted to tweet about a win on the same day!). These skills and workflow can be applied in future story maps I create. Plus, I felt like I was presenting something new and unique to both the golf audience—who likely aren’t familiar with story maps—and to the GIS audience, who may or may not be familiar with professional golf.

Applying new ideas

If a new idea for a story map strikes me, the first thing I need to do is think out how the idea will translate into something tangible on a map. Depending on the topic, this might be a quick process, or it could take days of mulling over what exactly it is I want to present to a reader. Here are a few questions that I ask myself when I’m thinking through a potential story map topic:

- Is location relevant to the story?

- Are there a variety of locations to be featured?

- Can text and media content be easily found?

- Would this be a worthwhile share on social media?

Is this something that other people might be interested in learning about?

If the answer to each of questions is yes, then I know I have something that is likely to work well as a story map topic. It’s also worth noting that a good story map does not need to be overly long; try to deliver a few key points or events to your readers. For example, if I have an idea for a Story Map Tour of locations where a movie was filmed, I will aim to present 10 to 12 locations on the map, not 30 or 40 locations.

Things to consider

If you’re a working professional and do not want to mix your personal stories into your organizational ArcGIS Online account, you could consider creating a free, public account that enables users to compose story maps for non-commercial purposes. Also, try to make use of publicly available content from official social media feeds and image content that has been labelled for non-commercial reuse. Always present public figures without personal bias and stick to the facts. If you refer to information from free-content websites like Wikipedia, be sure to include relevant hyperlinks about where it came from and when you accessed it on your story map’s item details page.

People have said to me on occasion: “I really want to make a story map. I have a few ideas… but I don’t know. I’m not sure if it will work, so I never actually make one.” Don’t be afraid to take the plunge! I often start out making what I think will be a good story map but if I find it’s not working out the way I had envisioned it, I’ll abandon the topic. People’s tastes in things like hobbies, sports, music or pop culture are widely varied, so there’s a good chance your story map idea is a unique one and other people will want to see it.

The more story maps you create, the stronger story mapper you will become.

Article Discussion: