Many people think of archaeology as brushing dirt off bones or what Indiana Jones does.

Matt Howland—graduate student and archaeologist at the University of California San Diego—lives the dream of many ten year olds. Digging. Exploring. Discovering.

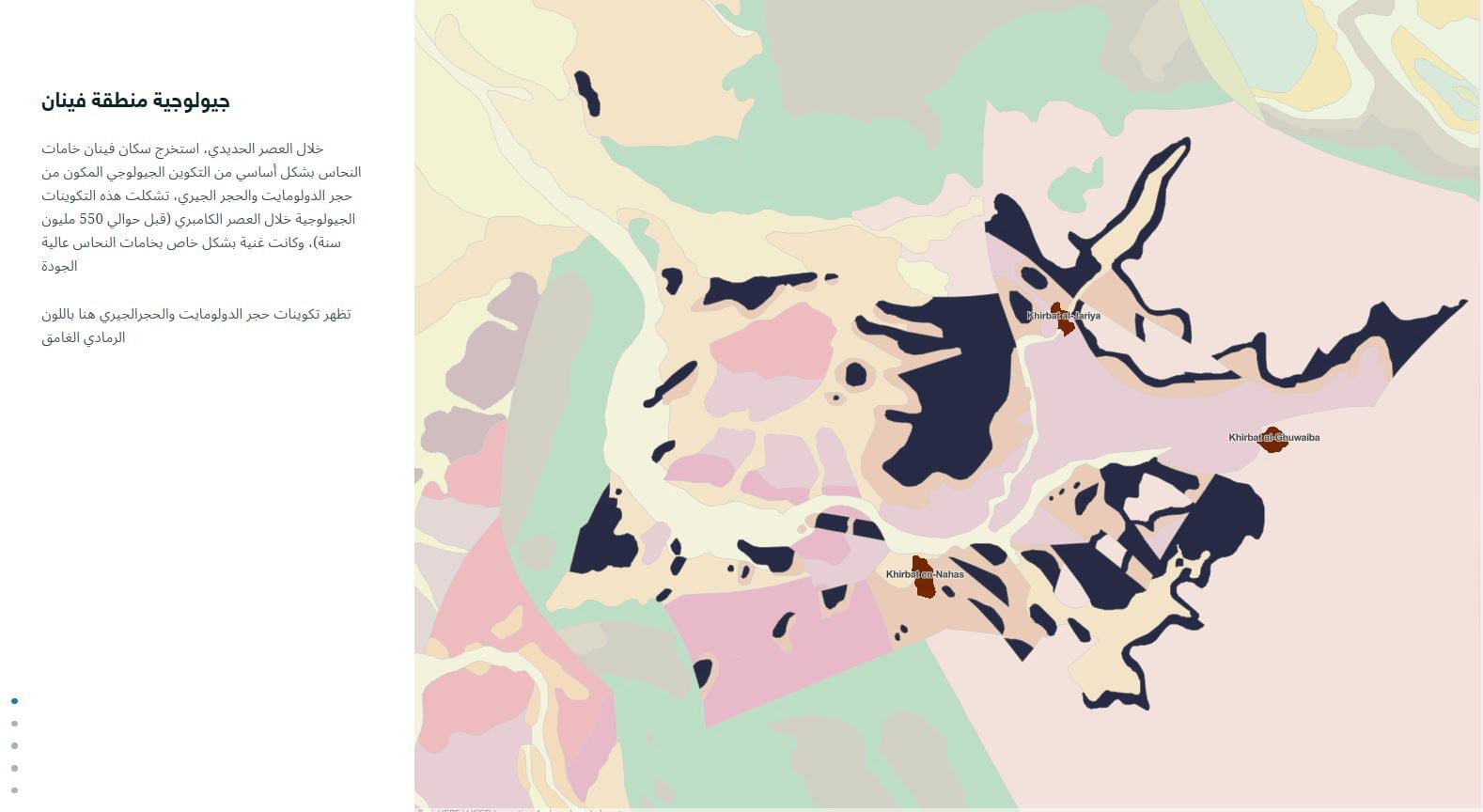

Matt is an archaeologist whose current work focuses on southern Jordan’s Faynan region during the early Iron Age period (ca. 1200-900 BCE), primarily at the copper producing site Khirbat al-Jariya. His interests include the role of trade and long-distance exchange in the development of social complexity and the economic lives of ordinary people in the past.

In order to investigate these issues, Matthew applies spatial analysis in GIS and 3D modelling with photogrammetry—definitely more sophisticated than the ten-year-old vision. But Matt has the perfect mentor for the sophisticated work, Tom Levy.

Tom is Distinguished Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Center for Cyber-Archaeology and Sustainability or CCAS in the Qualcomm Institute. He holds the Norma Kershaw Chair in the Archaeology of Ancient Israel and Neighboring Lands at UC San Diego, and is a member of the Jewish Studies Program. Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Levy is a Levantine field archaeologist with interests in the role of technology, especially early mining and metallurgy, on social evolution from the beginnings of sedentism and the domestication of plants and animals in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period (ca. 7500 BCE) to the rise of the first historic Levantine state-level societies in the Iron Age (ca. 1200 – 500 BCE).

We sat down with Tom and Matt to better understand storytelling in archaeological research and interpretation and the role of digital platforms, like StoryMaps, in sharing those stories widely.

We recently featured your story map—The Kingdom of Copper—on our website and social media channels, with an overwhelmingly positive response. Can you share a quick overview of the story map and your research?

Matt: Absolutely.

The Kingdom of Copper story map lays out—in plain language and with visuals—the economic and political boom in southern Jordan’s Faynan region during the Iron Age, which ran from around 1200 to 600 BCE. During that time, the society in Faynan became a major producer of copper and exported the valuable resource around the eastern Mediterranean. The story and our research focus primarily on how the region developed from a sparsely populated desert into a major industrial center over a relatively quick period of time.

The story also offers insight into the process of archaeological investigation.

Many people think of archaeology as brushing dirt off bones or what Indiana Jones does. We want to provide insight into how we learn about the stories of ancient societies—by showing some of the datasets we acquire and how we acquire them.

Your story mixes history and archaeology with interactive maps, video, and other multimedia. That combination and your clear narrative tell an engaging story that novice readers can understand. Can you talk a little bit about storytelling in your work?

Tom: Archaeology is really fundamentally a storytelling field.

Archaeologists gather evidence from many different sources, using many different methods, and then use that information to better understand how people lived in the past. In the 21st century, many of those sources of evidence are digital, such as GIS data, digital photographs, video, and 3D models.

While we use these datasets for analysis, they’re also great resources for showing the public what ancient societies left behind and what kinds of activities the average person did in the past. For example, the process of copper smelting in the Iron Age generated tens of thousands of tons of copper slag, which has a characteristic black appearance and is piled in mounds at copper-producing sites in Faynan. In our story, we show people the remnants of slag that we, as archaeologists, use to understand the scale of ancient copper production, and help readers to understand its significance for that purpose.

So, in a way, we’re helping readers to see things from our perspective and both understand the past and also how we’re able to interpret the past in greater detail. We’re also sharing the story map with the archaeological community. It was immediately well received as an engaging and entertaining way of disseminating our research in Faynan.

Can you speak to the role of geospatial information in archaeology and stories about the past?

Matt: Just as archaeology is a storytelling field, it’s even more so a fundamentally spatial field.

In archaeology, everything we know comes not from finding individual artifacts, but from understanding artifacts in context. An individual piece of slag by itself is meaningless, but a pile of slag at a site indicates that copper smelting occurred at that site. Understanding spatial relationships in archaeology is critical for the work we do.

On the Edom Lowlands Regional Archaeology Project or ELRAP, directed by Professor Levy, we spend a lot of time carefully recording locations of artifacts. In total, these datasets, recorded and analyzed in GIS, allow material remains to become puzzle pieces for understanding and telling stories about the past.

Matt, we understand that you’ve been involved in promoting GIS at UC San Diego. Can you tell us a little about that?

Matt: Well, GIS has been a significant part of my archaeological research since I studied GIS and archaeology as an undergraduate at Penn State University. There, I learned the importance of interpreting space for understanding the past. And passing on those GIS skills and their application to archaeology and anthropology became really important to me.

The Levantine and Cyber-Archaeology Lab at UC San Diego places emphasis on GIS and technology, so it was a natural fit for my graduate work. Fortunately, I was given the opportunity to develop and teach my own course in the Anthropology Department—Introduction to GIS for Archaeologists and Anthropologists.

So far, I’ve received all positive feedback from students on our very STEM-oriented campus. They’re excited about applying GIS to their own research in the social sciences.

How and why did you transition into story maps for sharing research?

Matt: I first learned about Esri’s storytelling tools during a Make the Most of Modern GIS workshop held by Esri and hosted by the UC San Diego GIS Library. I immediately recognized the potential for storytelling and for introducing a wider audience to the many types of digital and spatial datasets that help us understand ancient societies.

The interactivity was appealing – giving readers the freedom to explore the content and then draw their own meaning from the archaeological data. This is an important part of engagement with cultural heritage.

The power that an internet-based storytelling method has for engaging people across the world was also a big draw. Our ELRAP team is primarily composed of Americans and Jordanians, but we haven’t previously had the opportunity to share our work in the UC San Diego labs with the locals of Faynan and the citizens of Jordan more broadly.

We translated our story map into Arabic in order to engage with the local communities whose cultural heritage we are researching. We want to keep a dialogue open with Arabic-speaking communities—a platform for two-way discussions about the culture and interpretation of the culture.

What’s next for you in story maps? More research studies? Classroom teaching? Different approaches to the actual research process or data collection?

Tom: In the field, we collect data that is, for the most part, already spatial data and well-suited for inclusion in a story map. Moving forward, I see story maps as a valuable tool for publicizing our research and telling the stories of the ancient societies. A story map for each of our field projects would be a great way to make our research accessible.

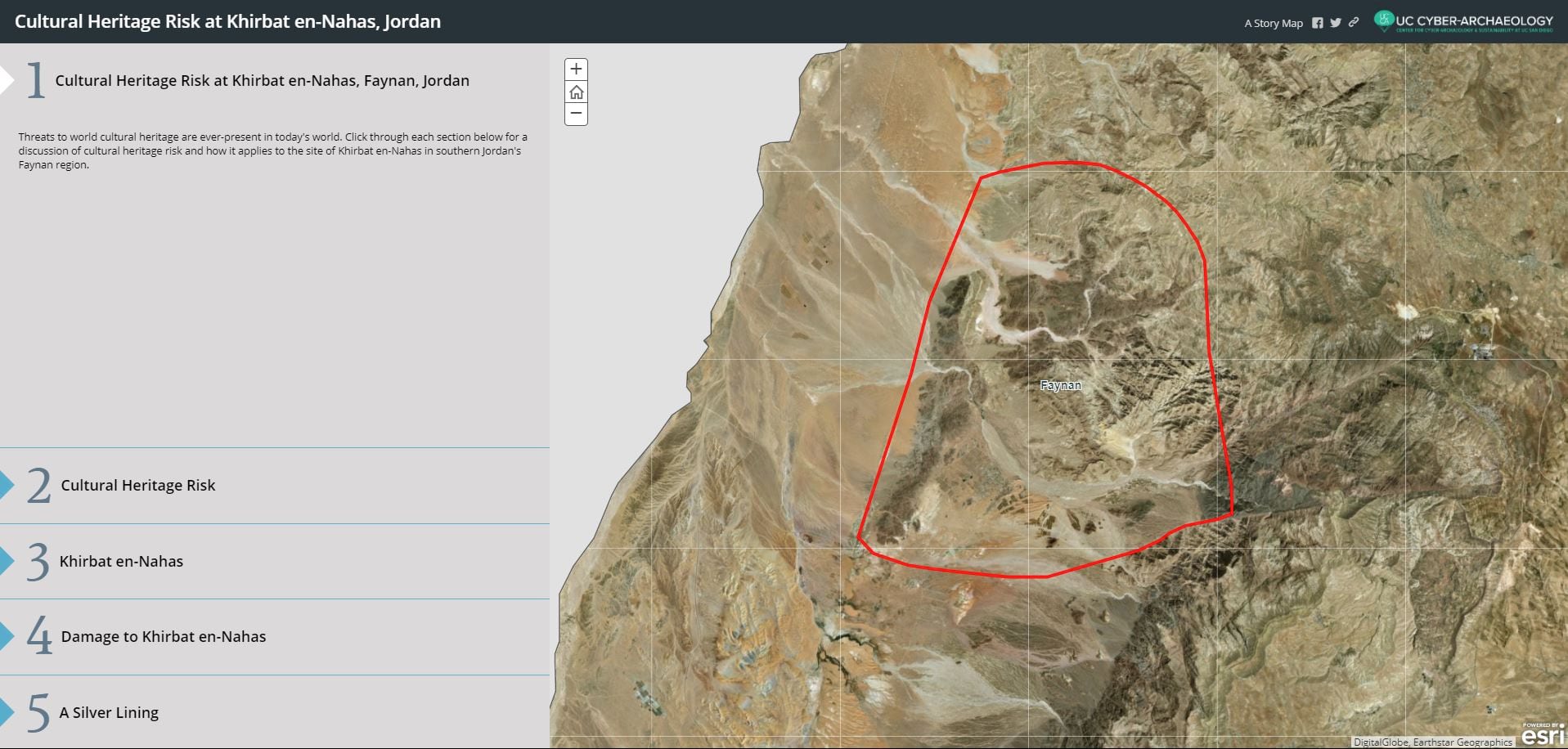

We also will use story maps to tell specific, relevant, and timely stories as needed—including the ever-present need to spread the word about cultural heritage risk. Worldwide cultural heritage is always under threat from a wide range of dangers, including climate change, urban and industrial development, warfare, and intentional destruction. We’ve already generated one story to raise awareness about these risks: Cultural Heritage Risk at Khirbat en-Nahas, Jordan.

What storytelling advice do you have for other scientists or academics?

Matt: Academic archaeologists often record their findings in academic journals, edited volumes, and other academic publications that don’t have much of a chance to filter out to the general public. As archaeologists, we have a responsibility to open our process and our results to the public.

The way that stakeholders understand their cultural heritage sets a baseline for how archaeologists can and should interpret the past. Fortunately, a lot of the digital datasets that we collect these days easily lend themselves to sharing widely with interested groups on digital platforms like ArcGIS StoryMaps. While not everyone has internet access, it’s certainly a start to be able to bring interested people in and engage them in the process of learning how we understand the past.

Article Discussion: