Have you ever thought about the many unique ways people experience the world? According to the WHO (World Health Organization), at some point in life, roughly 16% of people will experience significant challenges or disabilities that impede navigating the world or accessing online content. These challenges can include everything from short-term physical injuries to long-term paralysis, to cognitive and intellectual challenges, to motor or vision impairment—especially as humans age.

As storytellers, Esri’s ArcGIS StoryMaps team strives to provide examples for how you can create your best stories using GIS data and maps. We’ve previously shared general information on accessible content, why it’s necessary, and how to get started creating it. Now we’re sharing examples of how to structure alternative text for complex media that we’ve used to create stories that provide not just an accessible experience, but a more equitable and inclusive one, too.

Accessibility as a standard

When we think of accessibility, many of us think first of the ramps accompanying stairways or the sidewalk curb cuts that are standard in most public spaces. In terms of the Internet, accessibility means to provide a product or service that can be used by everyone, and ideally with a similar level of ease. Much like stairway ramps, creating well-designed, accessible content can benefit everyone.

The ArcGIS StoryMaps builder includes integrated accessibility tools that allow you to create stories that meet WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) standards. It also includes a contrast checker to ensure your text is visible against the background of a story, which makes creating an attractive and accessible custom theme for your story much easier.

Alternative text as a standard

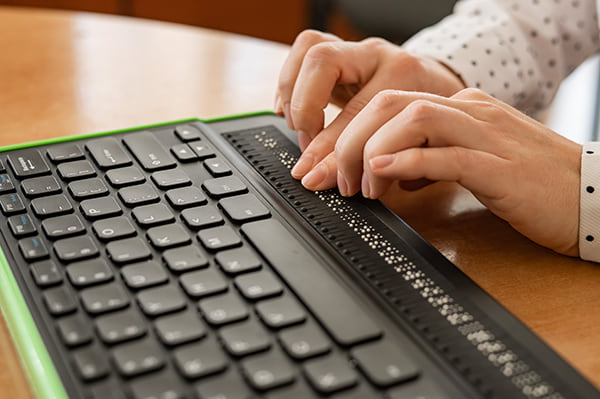

Alternative text, also called alt text, which is a standard feature for many websites is useful in case the media, including maps, is not displayed because of bandwidth limitations, slow internet speeds, and broken links. Screen readers and other assistive technologies also know to look for alt text to describe the media.

Within the ArcGIS StoryMaps builder, you can add alt text to all media by entering the options panel (the gear icon) for the media, see this video for a brief demonstration of how to add alt text in a story. (Pro tip—we recommend writing and editing alt text in a text file first, and then pasting it into the StoryMaps builder.)

The goal for alt text is to describe the media, map, or graphic as succinctly as possible. One rule of thumb is to try to keep alt text to 125 characters or fewer (and often skip the ending punctuation, too). While that usually works for simple photos, a 125-character limit may not provide a fully equitable experience when it comes to maps or complex graphics. When brevity conflicts with providing your audience with a more equitable experience, to help you decide how to best share your content and balance your audience’s needs, you may want to consider the options below.

Creating equitable experiences

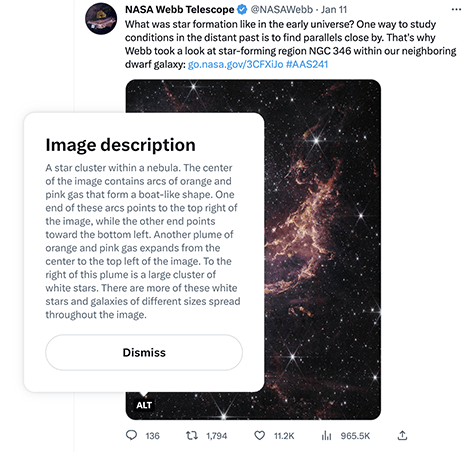

The first possibility is simply to break that 125-character barrier. One example of fantastic alt text is from NASA’s Webb Telescope photos that made headlines over the summer of 2022. The positive reaction these descriptions received confirmed what some of us have suspected for a while: that many audience members appreciate an equitable experience, even if it’s a little wordier.

Another option is to explain your media more within the story’s running text. However, it might not be possible to efficiently provide ample information in the copy to say what you created the graphic or map to communicate. Sometimes adding extra text would even be the antithesis of why you created the map or graphic in the first place—to illustrate, simplify, or efficiently explain a concept.

For complex maps and graphics one more possible solution is to narrate those parts of your story with audio files to explain your maps and ensure that your story is understood by your entire audience.

Finally, some organizations encourage providing a spreadsheet of data along with a map when it’s practical for the map context, such as locations of medical facility addresses. However, a spreadsheet is not always an ideal solution, especially when you’re working with large data sets.

An animated example

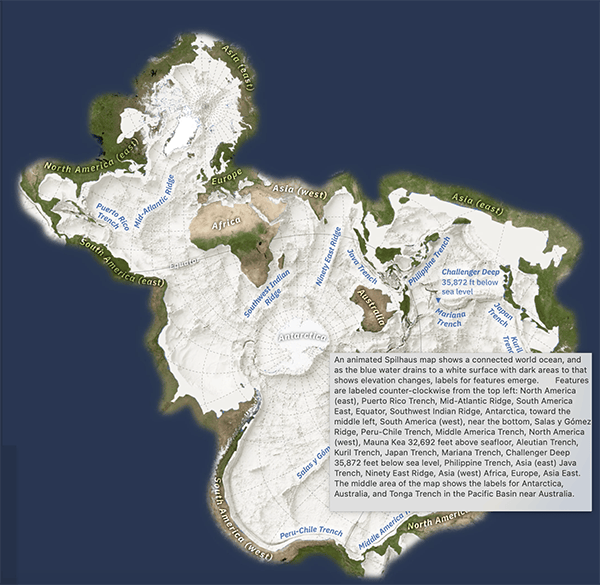

In Why we map the ocean floor, StoryMaps team cartographer Cooper Thomas created several animated maps—which, if I may interject, are some of the most visually striking maps I’ve ever seen. They’re also as complex as they are beautiful. The maps are a Spilhaus projection, which shows the ocean as one continuous body of water, with the land areas occupying the edges of the map, and was the perfect projection for the story content.

The Spilhaus projection is atypical for even the biggest fans of maps. It comes across as abstract when compared with more familiar projections such as a Mercator or Winkel Tripel projection. After the story’s introduction, the first Spilhaus map acts as a base for several maps that follow. When adding new layers of human-made infrastructure, the details made the animations even more complex. So, as content developers on Esri’s StoryMaps team, we had to pause and ask, “How do we create an equitable experience for those who are unable to actually see these maps?”

The solution we used for this story was to establish patterns in the structure of the alt text so the audience knows what to expect and can more easily process the description. The steps in the process are:

- Plan the alt text by building upon the map legend information, such as values or color, and the order that they are shown in the legend to help structure the descriptions

- Start the description by stating an overview sentence of the map’s purpose

- Establish the pattern for describing the maps, such as a grid system or a clockwise pattern; include other major points of reference to create context and reduce length of descriptions

- Share a description of the content noting if patterns exist, but not necessarily stating a conclusion

The first map in the series is used as a base, without the other layers. It includes major physical features that are used as points of reference for other layers. For the alt text, we started by explaining that the map was a world map and that it was a non-standard map projection. We continued by describing the shape and appearance of the projection, and then used a grid system to describe the map’s features, going counterclockwise from the top. We also noted in the alt text that the following layers were based on the initial description, and we would not include the full description of the base map after that.

After establishing this pattern in the first map, (the second map is shown below) we decided that we would be okay with only describing the patterns and pertinent information about the other information contained in the following layers. This allowed for a much shorter alt text description in the ensuing layers in the series that included both natural features and human-made features.

By establishing a predictable pattern, much like with broader storytelling strategies, you can help create a context and setting to help your audience understand and process the information more efficiently. We have used similar alt text strategies for other stories such as Justice deferred and Farm Animal Planet, among others. It’s also worth mentioning that all stories in ArcGIS StoryMaps produced by the editorial team include alt text.

Our ask from you

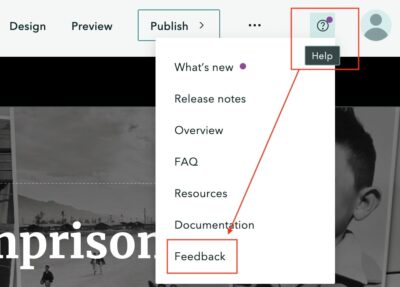

The team members who devised these strategies for alt text want to hear from you. What do you think? For feature suggestions for the StoryMaps builder we are listening, you can add your feedback to the form which is also available within the StoryMaps builder under the help menu.

We encourage all content creators and storytellers to share your thoughts on whether the strategies we used for complex graphics and maps are helpful for our community members who use assistive devices and to share your solutions or accessible story creation suggestions in the Esri Community ArcGIS StoryMaps. We also encourage you to share these stories and this blog with your community members as well.

Commenting is not enabled for this article.