As corporate decision-makers seek safer and more efficient business operations, they’re turning to digital twins to test assumptions—without real-world consequences. In this WhereNext Think Tank, Esri head of Professional Services Brian Cross interviews global chief technologist Mansour Raad about the implications of a new kind of what-if planning.

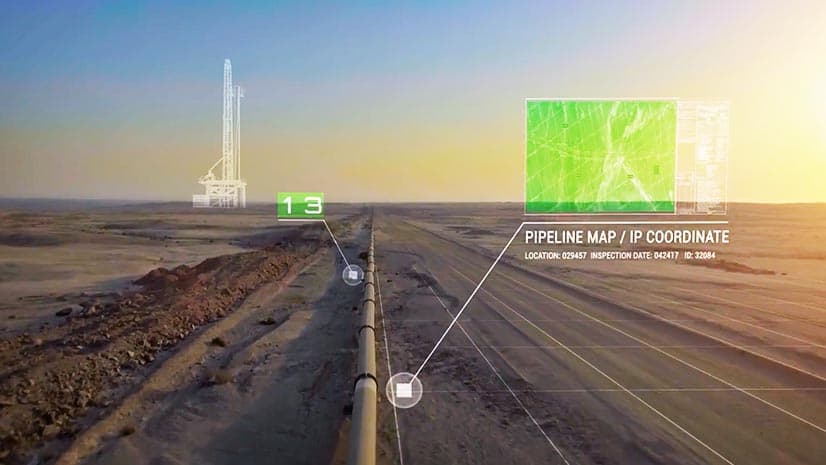

Brian Cross: We’ve heard a lot about digital twins lately, and the general premise is that a digital twin monitors the conditions of a system like a smart machine, a pipeline, a building, or a utility network. You’re exploring a new use for digital twins—can you explain what you’re working on?

Mansour Raad: As you know, there are a lot of interpretations of the digital twin concept. Here I’ll focus on digital replicas of a physical entity that rely on IoT technology, big data, and artificial intelligence to test expensive hypotheses in inexpensive ways.

We are consulting with companies on how to use that kind of digital twin to optimize certain aspects of their business. I’ll give you an example that involves moving data from place to place, but the same principles apply to managing cars or assets or people.

We’re working with a telecom company to optimize how data moves across its network. The company doesn’t own the fiber cables—it leases them, and one vendor might charge 1 cent to transfer data along a stretch of cable, while another charges 2 cents. Those decisions happen many times as data navigates the network. So the telco wants to know, “How can we move data as quickly as possible, at the lowest possible cost?”

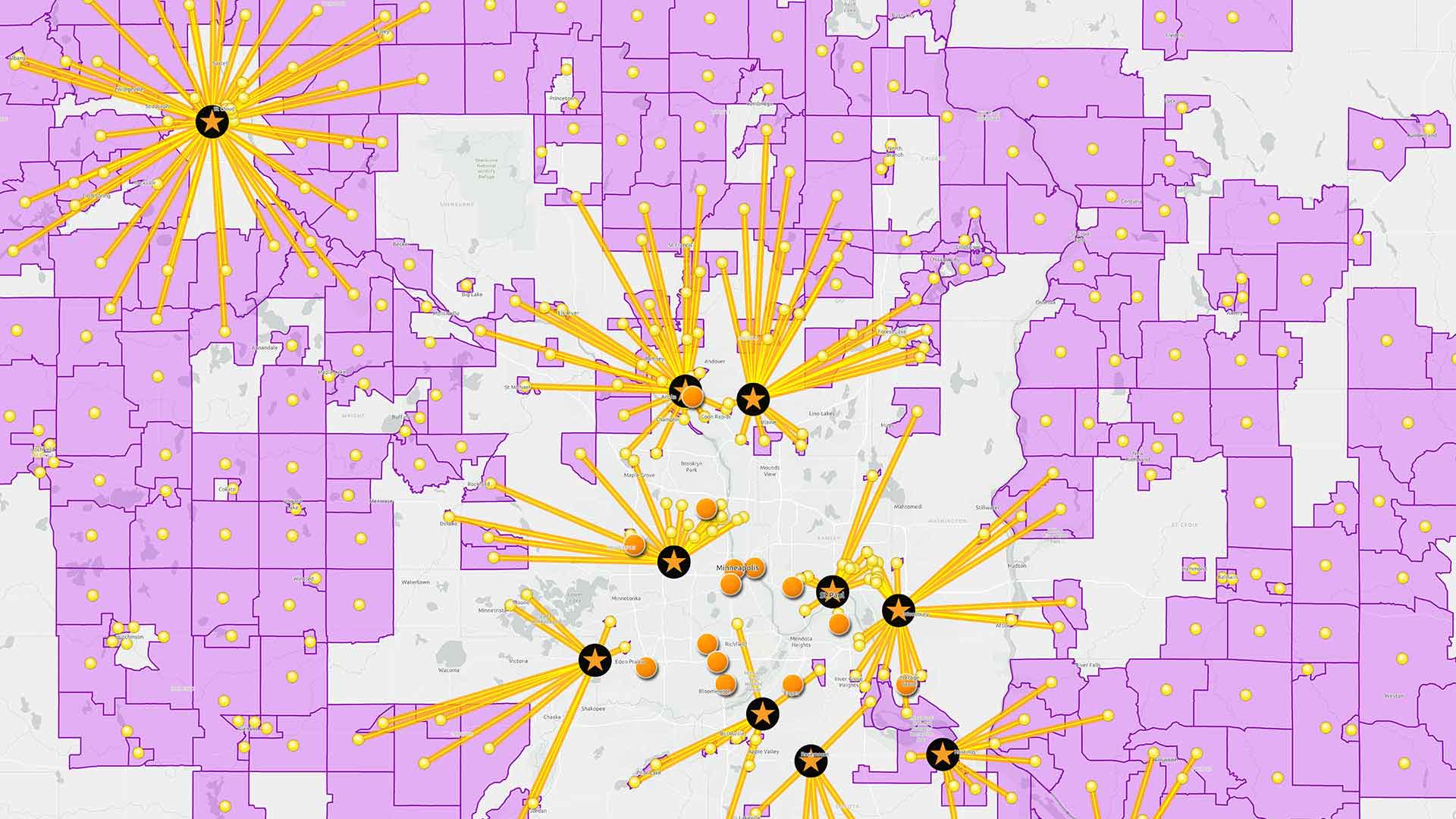

We used GIS technology to map the cables and generate an origin-destination matrix for the whole network. That became our digital twin.

Cross: That sounds similar to the digital twins we often hear about. What was the difference here?

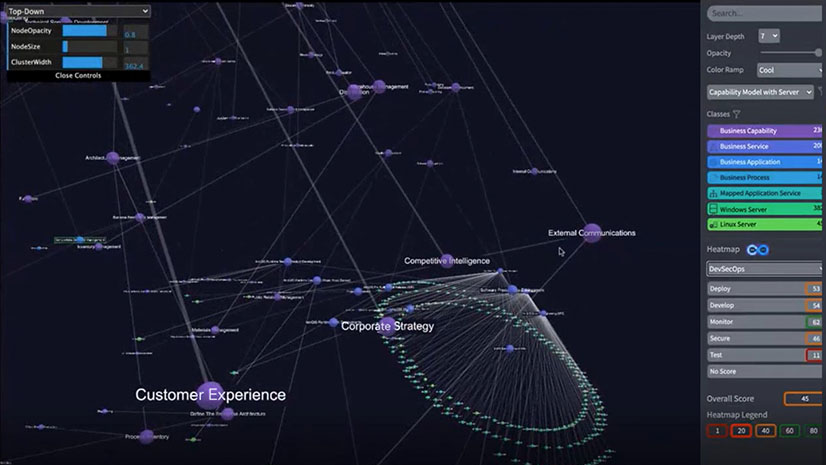

Raad: The main difference is that we use this kind of a digital twin to test out what-if scenarios, and we do it virtually so companies don’t have to worry about actual consequences. With a digital twin you can create virtual “monkey wrenches” to see how conditions change outcomes.

Because GIS technology uses machine learning, the software can calculate the optimal sequence of movements from any origin to any destination. In the telecom example, the software went through thousands and thousands of scenarios to figure out which routes cost less and saved time. Because we used a digital twin to do that, we could fail fast and discover better outcomes, and it didn’t cost the company anything—or very little, if they are using cloud computing.

The new trend is to run what-if scenarios on a GIS-based digital twin to test when and where conditions will change and how a business can respond.

Cross: Companies are building digital twins with a variety of systems. Why would they use GIS as a foundation?

Raad: When performing analysis with a digital twin, a lot of challenges that emerge are based on location—things like, Where are the risks in my distribution network? Where can I find my best customers?

Since location is the common denominator for understanding these kinds of scenarios, it makes sense to build digital twins on a system that specializes in managing and analyzing location data.

Cross: I think you’ve touched on the main components already, but what’s involved in what-if planning with a digital twin?

Raad: You need to know where each element of the network is in relation to other parts of the network, so we use GIS to map everything out. It could be a delivery van on a road network, or product components moving through the global supply chain.

With GIS-based machine learning, you can virtually test thousands of scenarios to find the optimal routes. And since it takes significant processing power to do that quickly, we typically use cloud computing.

Cross: What about the AI involved here—what kind of machine learning do you use?

Raad: It’s a form of machine learning called reinforcement learning. There is supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and now reinforcement learning—it’s emerging as a very popular alternative.

It’s very helpful for what-if planning and fail-fast permutations. It’s not brute-force machine learning, because with brute force it would take forever to figure out a solution. Instead, we basically introduce the concept of a reward, and the reinforcement learning program generates rules to optimize the reward, whether that’s time savings, cost savings, or another factor.

Cross: You mentioned the work you’re doing in the telco industry, which happens mostly behind the scenes. Are there other industries where this what-if planning taking off?

Raad: Lately we’re seeing companies apply the technique to supply chain planning, because today there’s so much complexity there, and so many unknowns. Executives are asking: What are the business consequences if suppliers in this part of the world can’t send us materials? How will we adjust? They want to play out as many scenarios as possible so they can prepare for whatever comes.

We’re also working with companies in the energy industry, because things are changing fast there. Globally, there’s a push to go green and decarbonize, and in the US, the Inflation Reduction Act includes a lot of funding for companies to build renewable energy capacity. So executives we talk to are asking, What if I put in wind or solar? Where would that happen?

Cross: Those questions are as much about business investment as they are about supply chain. How does a digital twin help?

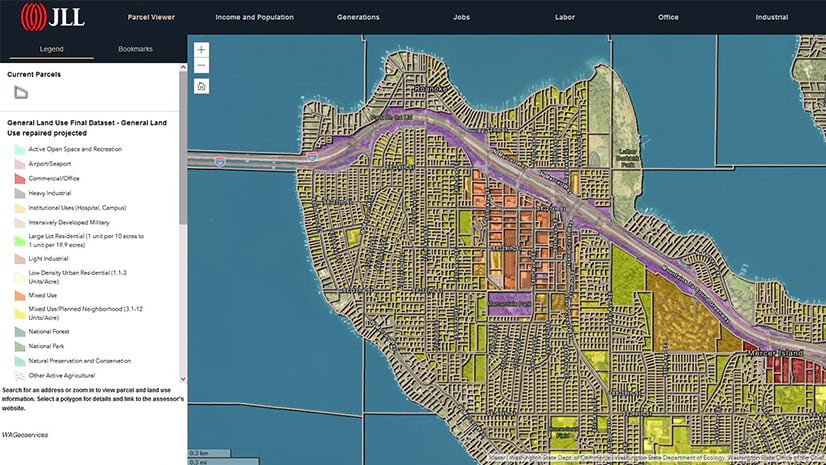

Raad: Executives want to figure out how to design a supply chain to bring these projects to life, and that’s a complicated equation. Like a lot of industries, renewable energy companies can only source components, like turbine blades and battery cells, from certain countries. They can also claim better tax incentives if they use domestic products, and many of those are defined through detailed geographic formulas.

On top of that, companies need to figure out where to locate the project. That’s like a retailer analyzing where to put a new store—they want to know whether the distribution network can reach the store, how far customers will travel to the location—all those factors. Energy companies weigh geographic variables like, How much sun exposure will I get if I install a solar farm here? What’s the break-even price for selling energy in this market based on my costs?

With GIS technology, we create a digital twin to analyze those factors and model what would happen in each scenario.

Cross: It seems like a common thread here is efficiency—moving products or people to the right places, establishing business operations in places that minimize time and expenses. That’s an age-old business challenge, but it sounds like it has some new implications.

Raad: Right. Sustainability is a new wrinkle. Companies are testing what-if scenarios to increase efficiency, and efficiency is a big factor in sustainability. If goods and people travel fewer miles, companies can reduce scope 1 emissions and reach net zero goals faster.

Another focus is safety. One of an executive’s least favorite factors is windshield time—the hours an employee spends driving from place to place. It’s basically nonproductive time, and it can also be the most dangerous part of an employee’s day. So we’re using digital twin techniques to optimize that work. Through machine learning, GIS software can analyze thousands of scenarios quickly and generate the optimal schedules and routes for employees to take.

That’s popular with natural resources companies that inspect remote equipment, companies with traveling sales teams or service technicians, delivery companies, and others.

Cross: Where do you see the use of digital twins evolving from here?

Raad: Today’s computing can process data at huge scales, and GIS tech is getting smarter all the time, so I think we’ll see more companies use digital twins to test what-if scenarios and fail fast.

Our conversations are expanding across industries, and it’s exciting to see the impacts of this new form of planning on business priorities like efficiency, sustainability, and safety.

Photo by Kelly Sikkema

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

November 12, 2018 |

February 1, 2022 |

July 29, 2025 |

July 14, 2025 |