The Reverend Kammy Young has seen the empty pews at Sunday morning service. She has read the surveys that show membership in decline. Once-thriving congregations now depend on part-time volunteers to keep their doors open. At a time when the relevancy of religion is in question, she feels a sense of urgency for churches to connect more deeply with their communities.

The challenges faced by Young and the Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast are not unique within the Episcopal Church. In fact, they’re not unique to the Episcopal denomination. During the past decade, the percentage of US adults who say they regularly attend religious services has been declining across every denomination and nearly every religion. The central question is how religious institutions might reverse that trend.

Young and many of her Episcopal peers have begun to believe that if they develop a deeper understanding of the communities around their churches, they will be able to connect in new ways with the people who live and work there. With that goal in mind, they’re moving to embrace innovative techniques pioneered by businesses around the world.

In the age of digital transformation, the Episcopal Church is using science to find the faithful.

The Old Ways Don’t Work Well Anymore

The old way of operating simply isn’t working anymore, Young says. “We’re no longer an established church that can just sit back, put our sign out front, and wait for people to walk in the door. We need to be engaged in our communities in significant ways in order to connect with people.”

The Reverend Tom Brackett, denominational manager of planting and redevelopment for the Episcopal Church, agrees. Part of the church’s decline, he says, may stem from complacency with the status quo.

“Many religious institutions tend to function at a very parochial level and only see within the bounds of what they’re comfortable tending to,” he explains. When that happens, “we lose perspective on the amazing work that’s going on all around us.”

Brackett and Young believe that successfully revitalizing the church depends on finding new ways to serve and connect with the community at large, not just those who regularly attend services. And they see location science as a tool to help drive those connections.

Creating a New Road Map Using Business Techniques

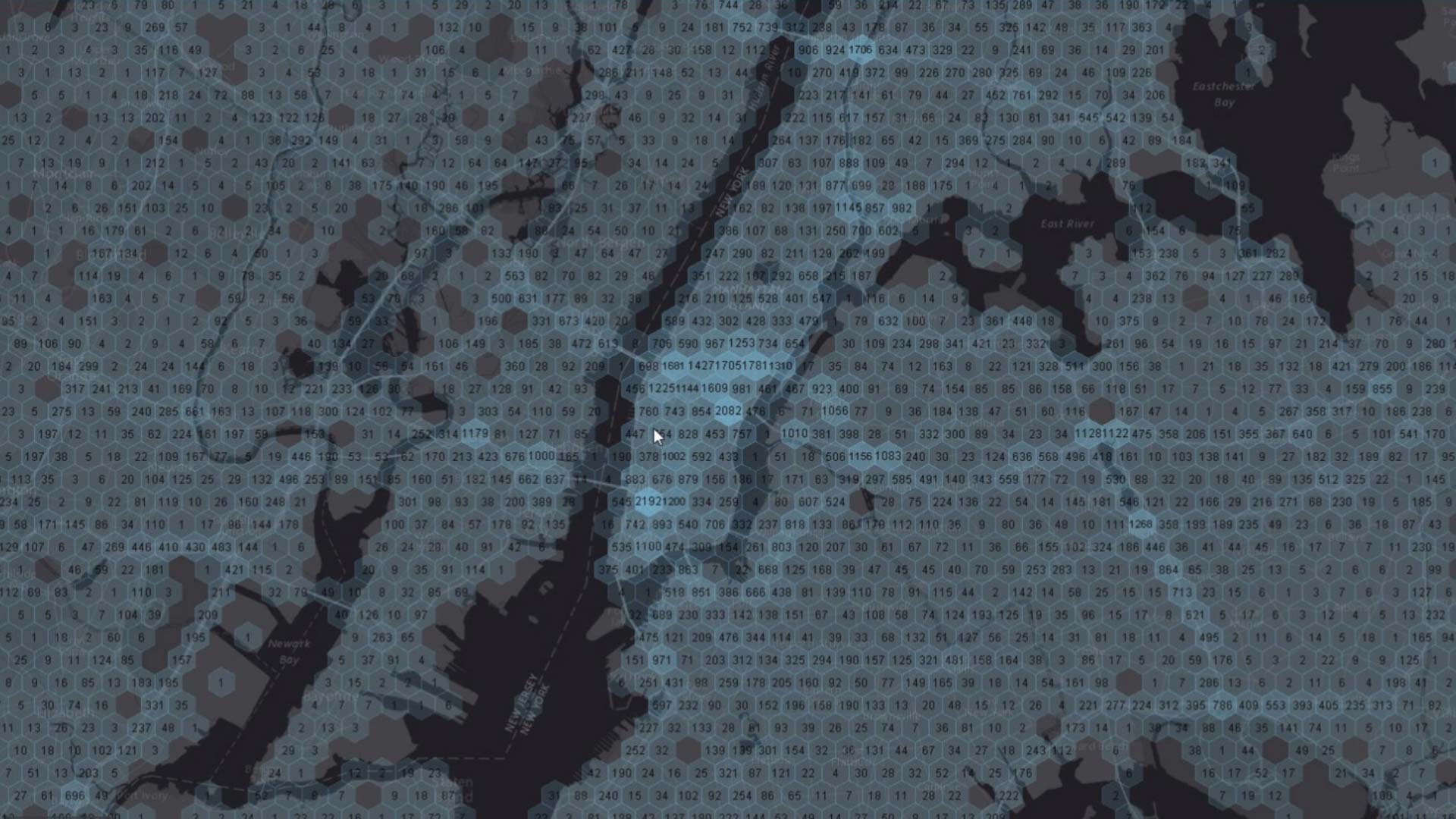

In its quest to revitalize the faith, the Episcopal Church has adopted a data-centered technology called a geographic information system. GIS produces location intelligence that gives the leaders of struggling dioceses insight into what may be causing congregation declines. In some cases, it illuminates how they might be reversed.

At the heart of the effort are smart maps that show faith leaders insights into their communities such as neighborhood demographics, drive times to places of worship, and the lifestyles and personal interests of nearby populations.

Businesses and other organizations have been using location data for decades to better understand customers and make well-informed strategic decisions. GIS helps them answer questions such as, ‘How many high-income customers are located within a 15-minute drive of this store? What is my risk exposure to a hurricane headed for Florida? If I place a store in this city, what effect will it have on my digital sales in the area?’

Church Challenges and Business Realities

It may seem odd for a religious institution to turn to the same technology that businesses use to increase profits. But in many ways, the operational needs of the Episcopal Church aren’t that different from those of a for-profit organization.

Churches rely on financial support from parishioners to stay open. When attendance declines, so can the financial stability of the congregation. Replace “congregation” and “parishioners” with “store” and “customers” and the explanation can apply to any retail business. Now, like executives in the for-profit world, church leaders are using GIS to identify opportunities for growth and retention.

Location intelligence is also helping church leaders make smarter decisions about church closures and consolidation. In some cases, smart maps identify areas where the population no longer supports the number of active congregations. In a similar business scenario, an executive may use GIS to understand how to consolidate underperforming stores while still serving the widest possible customer population.

The primary difference between a religious institution and a business is the emotional factor, according to the Reverend Scott Slater, canon to the ordinary in the Diocese of Maryland. Church leaders are forced to make business decisions about an institution with which they have a deeply personal relationship. Science-based tools like GIS bring clarity to those difficult situations.

Finding Growth Opportunities on the Gulf Coast

The Episcopal Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast was created in 1970 to meet the needs of a growing region in Alabama and Florida. Today, most of its 62 congregations are small and many are led by part-time, often retired clergy due to budget constraints.

When Bishop Russell Kendrick was elected in 2015, the Diocese was ripe for change. He brought fresh ideas and leadership to help reinvigorate the struggling region, including Young as the new canon missioner for development.

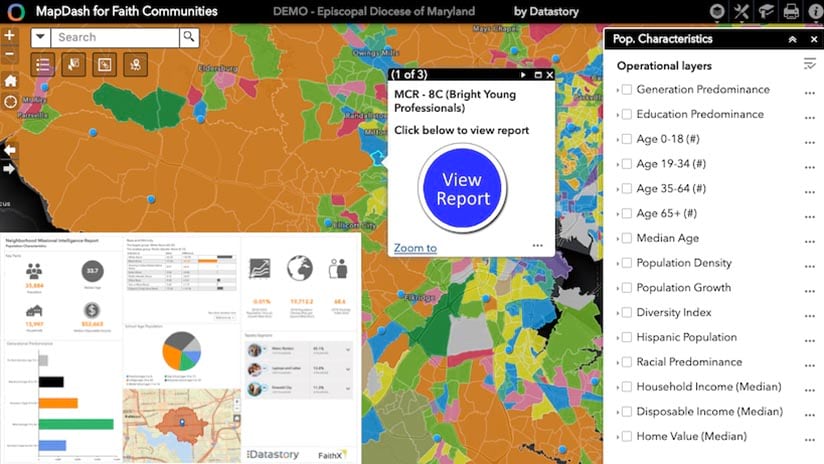

Last year, as she searched for ways to connect with the communities outside church walls, Young and a team of local church leaders began beta testing a GIS-powered tool called MapDash for Faith Communities, created by Datastory in collaboration with FaithX Strategic Missional Consulting.

“It would be irresponsible for us not to use the same kind of technology that businesses are using to decide where the market is and the best locations for their stores,” she says. “We need to be using the same tools for accomplishing the goals we have for God’s mission.”

Modern GIS tools reveal not only the demographics of neighborhoods, but how those demographics are projected to change in the years ahead. In one instance, Young and team used location analytics to identify an area forecast to grow at three times the national average over the next five years. That analysis helped them pinpoint opportunities to create new church ministries in the growing region. (See the map below for a sample analysis.)

Listening to Demographics

Successful companies “harvest every morsel of insight to understand where and how customers shop, how they engage with products, and what they expect from interactions with the brand,” Marianna Kantor writes in a recent WhereNext article.

Leaders of the Episcopal Church may use different language to describe their approach, but the same principles apply. For the church, the question is not just, who do we serve? but who should we serve—who are we overlooking?

For church leaders the answer is often: people who aren’t well-educated, white, and middle or upper class.

“One of the Episcopal mottos is Unity in Diversity,” Young says. “We value diversity theologically, but we don’t reflect it as much as we want to.” So she and her other church leaders are using location intelligence to get a deeper grasp of the communities around each church—revealing the ethnic composition of neighborhoods, for instance, or people of varying socioeconomic means.

“Not to go in and say, ‘We’re here to help now,’“ Young explains. “But to say, ‘We just need to learn to know you as our neighbors and build relationships of love that we think can bear fruit for everybody in the long run.’”

Keeping Pace with Rapid Changes

FaithX founder and executive director Reverend Ken Howard credits science-based tools with helping religious leaders understand demographic changes.

“People in churches and institutions of faith, they are used to learning about their communities through osmosis. [They’d] wait for the people to come and tell them about the community. But now, communities that used to change over generations change virtually overnight. So people are having to learn faster.”

GIS may reveal, for example, that a Hispanic population has flourished within a 15-minute drive of a particular church. That knowledge may prompt the congregation to post signs in English and Spanish, provide Spanish literature and Bibles, and conduct services in both languages.

It can also yield new opportunities to serve local needs. In the Central Gulf Coast Diocese, location intelligence revealed that six congregations were located near a Pensacola area where the literacy rate was far below the national average. Armed with that data, the congregations teamed up with the Children’s Defense Fund to establish a local CDF Freedom Schools for vulnerable children in the area.

The Reverends Young and Brackett both emphasize the importance of outreach in growing the church—a practice that echoes a business executive’s approach. In the era of digital transformation, business leaders are using location intelligence to better understand what their customers need.

Making Tough Decisions in Maryland

In the diocese of Maryland, Slater oversees the vitality of 106 congregations, which involves making tough decisions about church closures and budget allocation. He began working with GIS in the hope that data would “bring clarity to highly emotional situations.”

When he meets with leaders of struggling congregations, he delivers a report on average Sunday attendance. The report analyzes the past ten years of data and predicts the future. “In some cases, a congregation can essentially see their death date if nothing changes,” Slater explains. It can be a tough pill to swallow.

Occasionally, the revelation leads to the tough decision to close a congregation. But Slater hopes that more often, congregational leaders will be able to use the data to collaborate with nearby churches, rather than continuing to compete over parishioners. For instance, several smaller congregations may choose to start a Sunday school when it wouldn’t feasible for a single church to do so.

GIS-based analysis helps guide those decisions, according to Revered Slater. “If you don’t give people the data, you aren’t alarming them sufficiently to actually take action.”

Data and the Story of the Future

In the eyes of FaithX’s Reverend Howard, reliable data tells a powerful story.

“To actually teach people about their communities and teach them to collaborate with other people working in their communities, you have to present the data in a manner that they trust—using maps in this case. When you present it in a real-time, interactive way, they can say, ‘Well, show me this. Okay, now show me that.’ And then they begin to build the story of their own community.”

Episcopal leaders believe that location data has only begun to show its potential within the church. In a time of rapid change, they see location intelligence as a tool that can help light the path forward, diminishing uncertainty along the way.

“My hope is that in the next 10 to 20 years the church will be a more vibrant place,” Slater says, “because we’ll have more collaboration and fewer competing congregations.”

Young sees opportunities for faith to flourish through new tools and new interactions.

“We’re not going to think ourselves into the new way of being,” she says. “We’re going to have to act, and we can only do that by connecting with other people who are thinking differently and seeing things differently than we are. [People who] help call us into action outside our status quo.”

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

November 12, 2018 |

April 1, 2025 |

April 29, 2025 |

February 1, 2022 |