On Election Day, a democracy depends on voters’ having convenient access to the ballot box and an efficient way to get in and out of polling places. In New York City, that requires an increasing commitment to “smart city” technology.

In the nation’s largest city, more than 4.5 million residents are registered voters. Of those, 2.7 million cast ballots at more than a thousand polling sites during the 2016 presidential election. Last November, New York voters showed up in force again—this time to vote for governor. They recorded the highest percentage turnout for that race in nearly 25 years. And the big turnouts are expected to continue, as 2020 presidential campaigns already are capturing public attention.

Those are all signs of an engaged electorate, but they also stress the resources of any local government, much less a city of eight million, where small problems can quickly become big issues. Indeed, the malfunction of several New York City ballot-scanning machines during the 2018 elections led to frustrated voters, intense media scrutiny, and a review by government officials.

Establishing Operational Awareness

Intent on minimizing problems in the 2020 elections, Michael Ryan, executive director of the New York City Board of Elections, asked his staff to find ways to create operational awareness at the city’s more than 1,200 polling places.

With that many sites distributed over 300 square miles of a densely populated city and millions of voters trying to get to them on a single day, it’s an immense challenge, especially in a world-renowned city with an energized electorate.

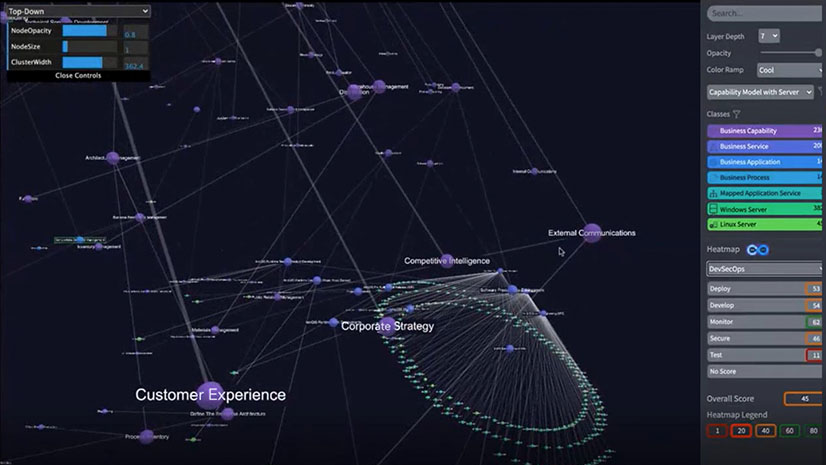

The staff responded by implementing technology that allows officials to see the city’s polling sites plotted on smart maps on mobile devices. Those smart maps act as a nervous system for the polling places, indicating at a glance—and in real time—how each location is functioning. The engine that makes it all possible is a geographic information system (GIS). The technology combines data feeds, predictive analytics, and dynamic maps (with 3D capabilities) to help officials spot concerns as early as possible and dispatch solutions quickly and efficiently.

Ryan framed the approach the way a forward-looking business executive might. “The more information we have,” he says, “the better our decisions will be.”

And Ryan knows how crucial those decisions can be. A city has just one day to facilitate a foundational process in a democracy: giving every voter a voice and making sure each vote counts. In that context, operational awareness matters because it delivers fast insight, allowing Ryan and team to swiftly triage issues.

Gathering Location-Based Intelligence for Disabled Voters

One of the board’s crucial tasks is to make sure the polling places remain in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) throughout Election Day.

When a malfunction with voting machinery causes long waits for repairs, it creates stress for all voters, but for disabled voters it can be more difficult to remain in the same spot for extended periods, or maneuver among a crowd.

During elections, however, designated monitors regularly review physical conditions at polling places to ensure access. Traditionally, they had paper checklists, which they completed several times a day. But to improve communications and response times, the elections board has now digitized and automated that checklist and developed a shared operations dashboard to monitor the combined results.

“When it was a paper form, if there was anything wrong, we really wouldn’t find out until a postelection dissection of the information,” says Vincent Parascandolo, project coordinator at the Board of Elections. “By using an app, we’re getting real-time information, and we can send staff immediately there to rectify the situation.”

The board continues to refine the mobile dashboard and share its location intelligence with the appropriate managers. That way, team members can back each other up during a hectic Election Day. “We don’t have to wait for the person who observed an issue to call in, or wait for a second person to let a particular borough know there was an issue,” Parascandolo says. “Because once that flag goes red, we have people monitoring the checklist results, and they’ll go in and investigate.”

And yet, developing situational awareness of all the polls does not guarantee quick fixes to problems, as poll workers know. That may require a different set of GIS solutions.

Efficient Dispatch for Field Technicians

When ballot-counting machines broke down during the 2018 elections and the need for repair personnel grew urgent, the stressful situation revealed an infrastructure that complicated response times.

In keeping with past practices, service technicians had been assigned to certain sectors. However, that arrangement hindered the board’s ability to dispatch the person closest to the polling place, regardless of zone.

“Right now, we do it by zones,” Ryan says of the service technicians in the field. “What we’d like to do is soften that border and make the personnel a little bit more fungible, or interchangeable, and move them across those lines.”

That organizational shift, combined with a technology shift, will help ensure a speedy voting process on Election Day.

As Ryan and team found, standard mapping alone doesn’t provide enough information to identify the technician who will reach the site fastest. But GIS-powered smart maps—which combine real-time data like traffic, train outages, road construction, and subway delays—can find available techs in the area and identify the one who will get there quickest.

“This is where traffic information becomes a real issue,” Ryan says. “Depending on where the problem is occurring, you might be closer to a location physically but further away in time because of some obstruction: a water main break or a car accident, for example.”

So what looks like a short trip, in fact, may be a long, stop-and-go journey by car or truck. Ryan says planners sometimes must be counterintuitive. “If people are moving around by train, and if the train’s out of service, then someone from a much farther location might have a different path to a particular poll site that is quicker, even though the map shows them to be much farther away.”

Realizing this, the GIS team is planning to integrate crowdsourced traffic data from a source such as Waze into the operational-awareness dashboard. To further increase efficiency, they may eventually map the real-time locations of field technicians, as many businesses already do.

A Dashboard for Operational Awareness

The dashboard apps also can incorporate data feeds from polling sites in much the same way that businesses track IoT-connected assets in the field.

For instance, if ballot-scanning machines had sensors to send signals about their current operating status, it would be possible to deliver alerts to field technicians or dispatchers about pending problems.

The use of sensors also raises the possibility of monitoring each site for what seemed to have been the culprit that caused paper jams in ballot scanners during the 2018 elections: humidity.

As the two-page ballots absorbed moisture from rain and humidity on that November day, they might not have appeared different to the naked eye, but some apparently grew slightly thicker and beyond the tolerance of the machines’ settings.

When the scanners jammed, long and growing lines meant some voters had to return to work or home without casting a ballot. However, if IoT sensors could track the relative humidity inside polling sites, along with the status of ballot-scanning machines, the locations of field technicians, and traffic flows, then managers would have the operational awareness to head off potential problems.

3D Maps for Better Visibility

With the fast-paced change of technology and ever-improving computer power and storage, as well as a powerful GIS that can keep adding applications and layers of data, where does the elections board innovate next?

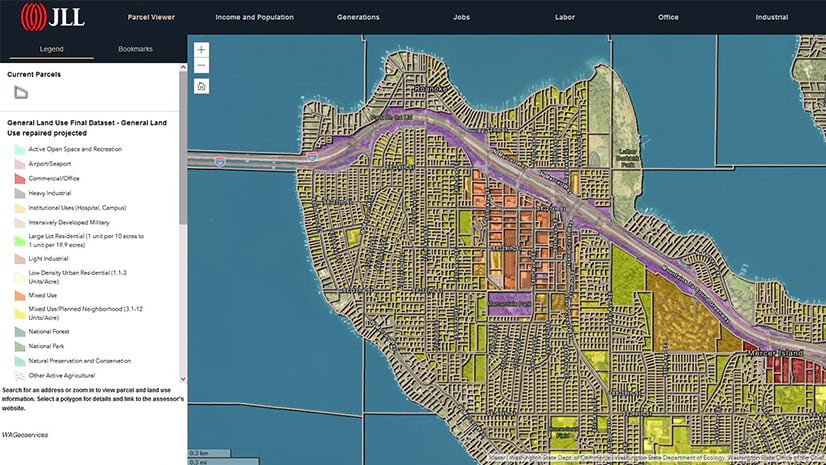

One of the most advanced features of location-based intelligence is the use of 3D imagery in maps. The elections board is exploring a 3D approach, including a more efficient way of finding convenient, accessible voting sites.

Two-dimensional maps can be misleading when used to decide where to locate polling sites. Moving a site by a quarter inch on a map may seem inconsequential, but a dynamic, electronic map with 3D imagery can reveal significant barriers.

“You get quite another sense when you really see the topography of the neighborhood with its hills and downward slopes,” Ryan says. “Then you realize that perhaps moving [a polling site] that block and a half might present difficult challenges, particularly to older or infirm people or those who have mobility issues.”

A consequence of overlooking such factors was driven home for Ryan when a person in a wheelchair referred to certain steep blocks in the city as “hand burners,” referring to what happens when someone in a wheelchair must navigate a long, sharp descent.

Other physical surroundings that can negatively impact voter turnout range from a six- to eight-lane roadway that a person must cross to an area of heavy construction activity that must be traversed. A smart city with location-aware technology can work to reduce those hazards.

Ryan also noted that future versions of the board’s smart maps may include information on buildings that are ADA compliant, 3D drawings of prospective sites, and notes on why the buildings would or would not make good polling places. Population trends and changes in business establishments are another form of location intelligence that can be layered into the smart maps. Taken together, that information can help the board sort out the best spots for early-voting sites or Election Day polls.

Ryan says the technology improvements will help the election board reach three vital goals. “Convenience to the voter and making sure that we identify convenient poll sites for the voters—that’s number one. Number two is keeping up-to-date about knowing what buildings are available in particular locations. And three is the ease of transmitting all of that information to staff, which is helpful to us in our planning process.”

Reaching those goals also helps produce a smarter city—one that provides easy access for more than 2.5 million voters. In the end, those are the people who will help keep democracy vital.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

November 12, 2018 |

February 1, 2022 |

July 29, 2025 |

July 14, 2025 |