In the 1990s, at the dawn of the Internet era, it was common to hear speculation about “the death of distance” and “the end of geography.” Some predicted the rise of digital tools like email and e-commerce would make location nearly meaningless.

Over three decades later, business and geography are as enmeshed as ever.

Consider the rise of artificial intelligence (AI): Today’s most talked-about technology operates on the level of neural networks and algorithms that seem untethered to the physical world. Yet the gigantic compute power for AI innovations comes from data centers that occupy fixed locations and could account for as much as a third of new electricity demand in the US over the next two years.

That leaves companies like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google attempting to balance the build-out of data centers against location-specific risks like flooding and heat waves, as well as corporate net-zero goals.

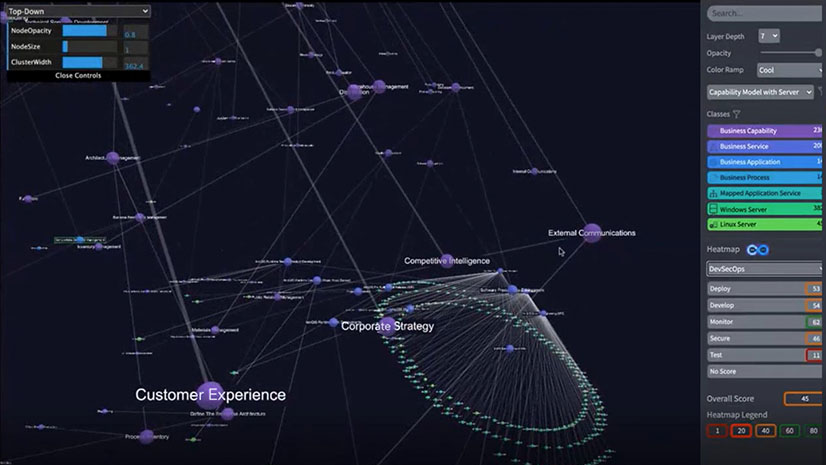

It’s just one of today’s business challenges that’s all but impossible to solve without a map and the kind of context provided by geographic information system (GIS) technology.

Geography and Business—Intertwined in Strategy and Operations

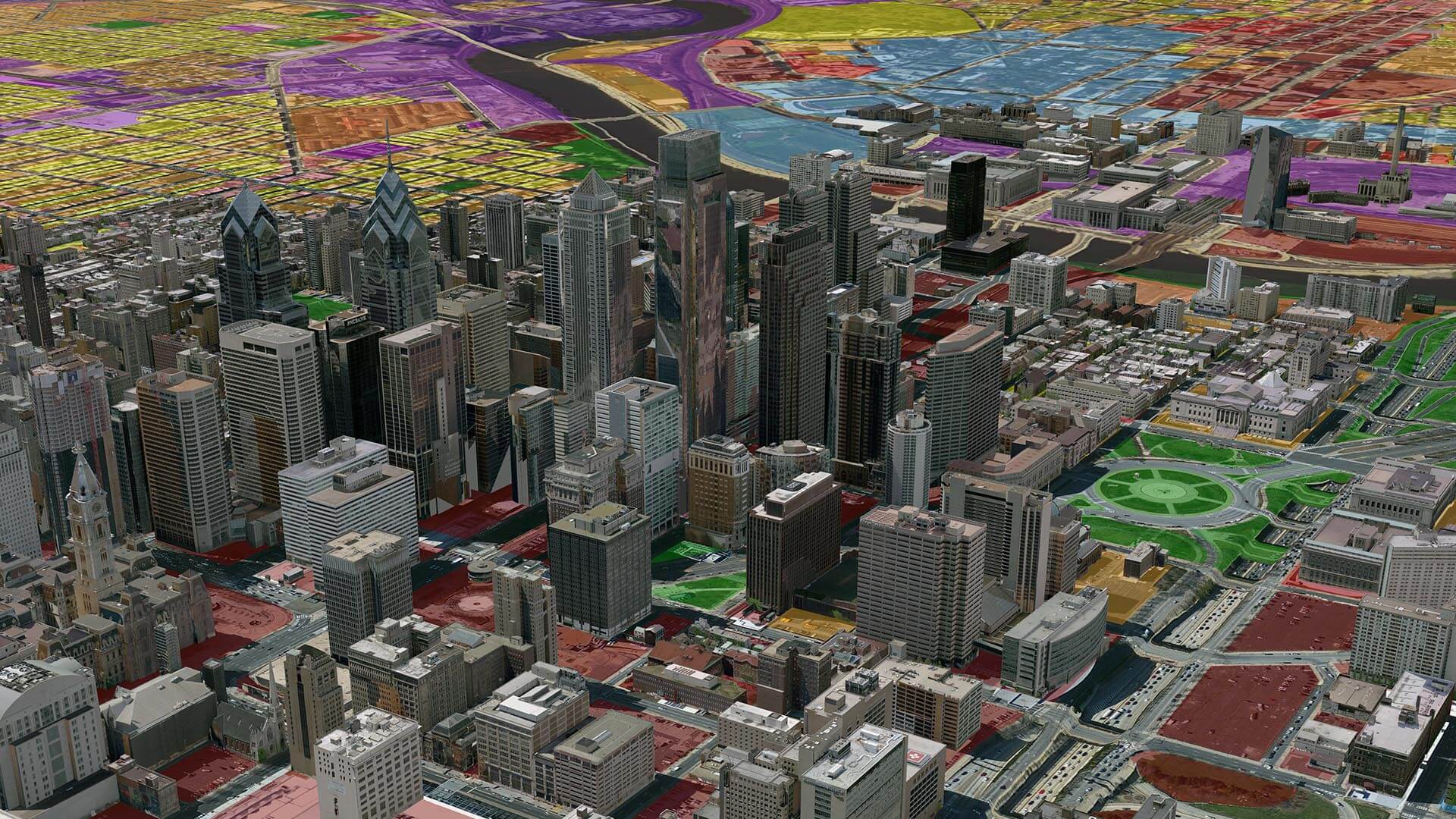

A geographic approach allows executives to assess markets and analyze business operations in the context of global supply chains, environmental impacts, security risks, and other data. Operational basemaps have enabled timber companies to develop sustainable forestry programs that ensure healthy woodlands for decades to come, and have inspired omnichannel retail strategies that spark growth online and in stores.

Geographic context also strengthens the hand of business leaders making tactical decisions. Smart maps can illuminate consumer trends that guide site selection for a new store, or shed light on risks posed by a factory’s water supply in a water-stressed region.

Business trends come and go, and industries rise and fall. But as long as people, nature, and businesses interact in specific locations, geography will matter.

In nearly every field, GIS is unlocking the business advantages of geography and steering companies around its risks.

Geopolitics, Fiscal and Monetary Policy, and Regulation

A company’s exposure to tariffs, taxes, and fiscal rules ties directly to location. An operational basemap allows companies to swiftly identify supply chains impacted by rules like the European Union’s carbon tax on imports. That awareness could help decision-makers target assets with poor energy efficiency or determine where carbon reduction systems would limit fees.

Such assessments involve a decision framework known as an OODA loop, which JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon praised in his most recent letter to shareholders: observe, orient, decide, act.

Any decision-making involving the latest developments in global trade and fiscal policy begins with assessment—and assessment inevitably requires a grasp of location. Tactically, for instance, a bank might use GIS to analyze satellite imagery, assessing whether an agricultural company seeking investments conforms with biodiversity laws.

Amid the shifting geopolitics of international trade and a slew of climate-related regulations, GIS is providing critical context as executives observe policy adjustments and orient their enterprises to the changes.

Business Growth, Market Analysis, and Supply Chain Design

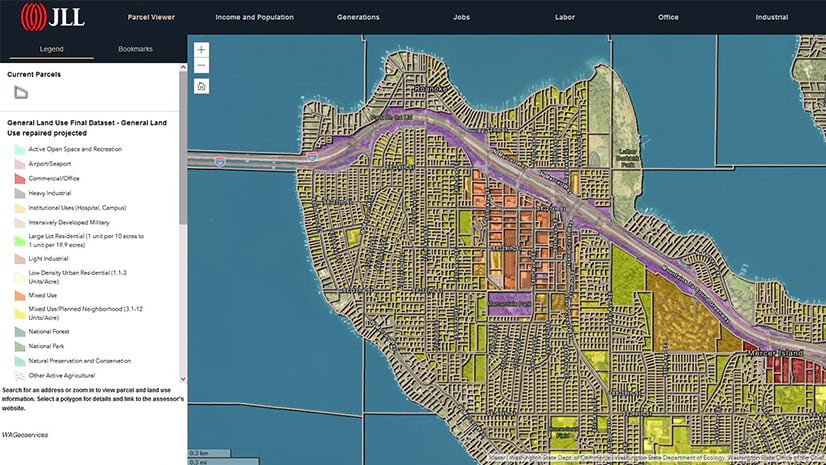

Businesses seeking expansion underestimate the importance of geography at their own risk. Some American retailers have famously stumbled when expanding, often because they overlooked the nuances of location.

One prominent US retailer grew its store count to more than 5,000 in the middle of the last decade, making it a familiar landmark in most major cities. The CEO once counted eight stores operating within five miles of his house. But most locations couldn’t support such density, and stores began to cannibalize each other’s sales.

The right kind of assessment can unearth geographic trends conducive to success. At one of the Big Four advisory firms, location-savvy consultants use a GIS map enriched with population and zoning data to guide an e-commerce company to the most promising shopping district and even the best street for a new storefront.

Top retailers routinely use geographic and demographic analysis to choose store locations and design supply chains to support them.

Demand for analysts who understand the geography of logistics and shipping routes is so great that companies are partnering with universities to sponsor GIS-based competitions.

Climate Risks: Where to Bolster Resilience and Reduce Negative Impacts

In its annual Global Risks Report, the World Economic Forum revealed the top four long-term risks identified by experts in business, academia, and beyond. All four are environmental—including extreme weather events and biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse—and all behave differently in different geographies.

Businesses are adopting a two-pronged response focused on reduction and resilience. At the heart of that approach is a geographic view of factors they can control—like their carbon footprints—and those they cannot, like projected sea level rise and predicted flooding impacts.

Some companies are building resilience with help from location technology by assessing which climate risks will affect certain geographies. Others are reducing their carbon profile by assessing operations in specific locations. One Swiss retailer used GIS to map the speed guidelines and road gradients of its truck routes to plan the most energy-efficient distribution strategy.

Optimizing Access to Natural Resources and Human Resources

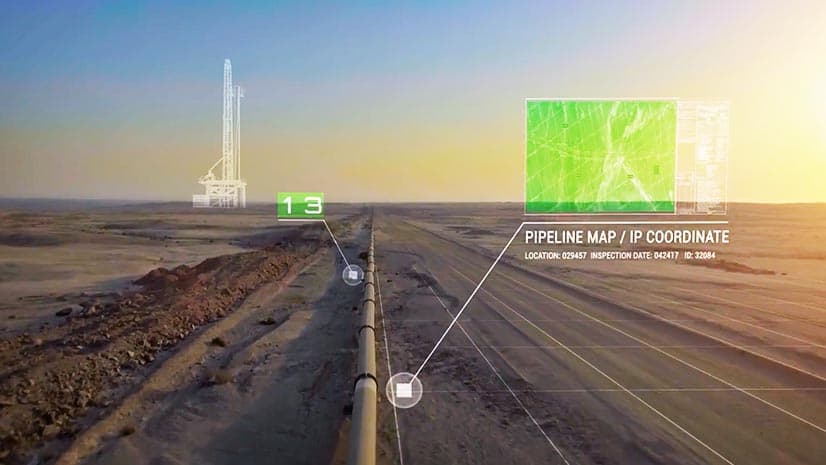

A company’s geography determines its access to critical resources like lumber, mineral deposits, and water, and to the specialists needed to fill vacancies. Today, those insights are delivered at scale and in real time thanks to innovations in GIS.

For executives, smart maps can show the location of potential ore mines, harvestable timber, or potential preservation land. Just as importantly, they can indicate the roads heavy machinery might use to access a site, along with nearby conservation areas and available labor pools.

Water, a resource that many companies took for granted a decade ago, has become the number one sustainability concern for executives across industries. For a chipmaker whose semiconductor fab uses millions of gallons of water a day, reaching next decade’s growth target might require avoiding areas of water stress. Maps can highlight geographic regions less likely to be affected by drought.

GIS is also empowering workforce analysis. An HR executive can map market data on salaries across various regions and use that information to hone their hiring strategies in different locations.

Connecting with Communities and Customers

One way to describe the rise of the triple bottom line is that companies have broadened their pool of stakeholders. Whereas shareholders were once the sole focus, executives increasingly want to understand the relationships between products and services, customers and communities. That understanding is rooted in geography.

When one of the world’s largest tech firms sought to support nonprofits assisting Black Americans as part of an equity initiative, geography was a critical factor. With location technology, program leaders analyzed housing, education, and poverty data to identify areas of profound racial disparity. They then partnered with local nonprofits, provided them with funding and digital tools, and tracked equity indicators in the communities to measure the impacts of the program.

Companies are also increasingly lending support on the front lines of disaster response. Big retailers have used operational basemaps to distribute resources including masks and sandbags from warehouses to neighborhoods of need. They’ve also helped authorities stage water and food distribution sites in company parking lots.

The location data needed to perform these and other strategic tasks—in other words, to help companies orient and act—is growing in volume even as it decreases in cost, according to Deloitte & Touche managing director Jerry Johnston. As long as companies need to understand where something is—customers, competitors, resources, risks—geographic context will continue to grow in value.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

November 12, 2018 |

July 25, 2023 |

February 1, 2022 |

July 29, 2025 |

August 5, 2025 | Multiple Authors |