Behind the seamless rollout of every software product, there’s a story of ingenuity, hidden hurdles, and digital MacGyvering. Such is the saga of NatureServe Explorer Pro, the groundbreaking biodiversity tool from North America’s leading biodiversity information provider, NatureServe.

A combination of technological wizardry, agile management, and the occasional nature walk helped the Washington DC-based nonprofit surmount numerous obstacles in a multiyear journey that culminated in a powerful new tool.

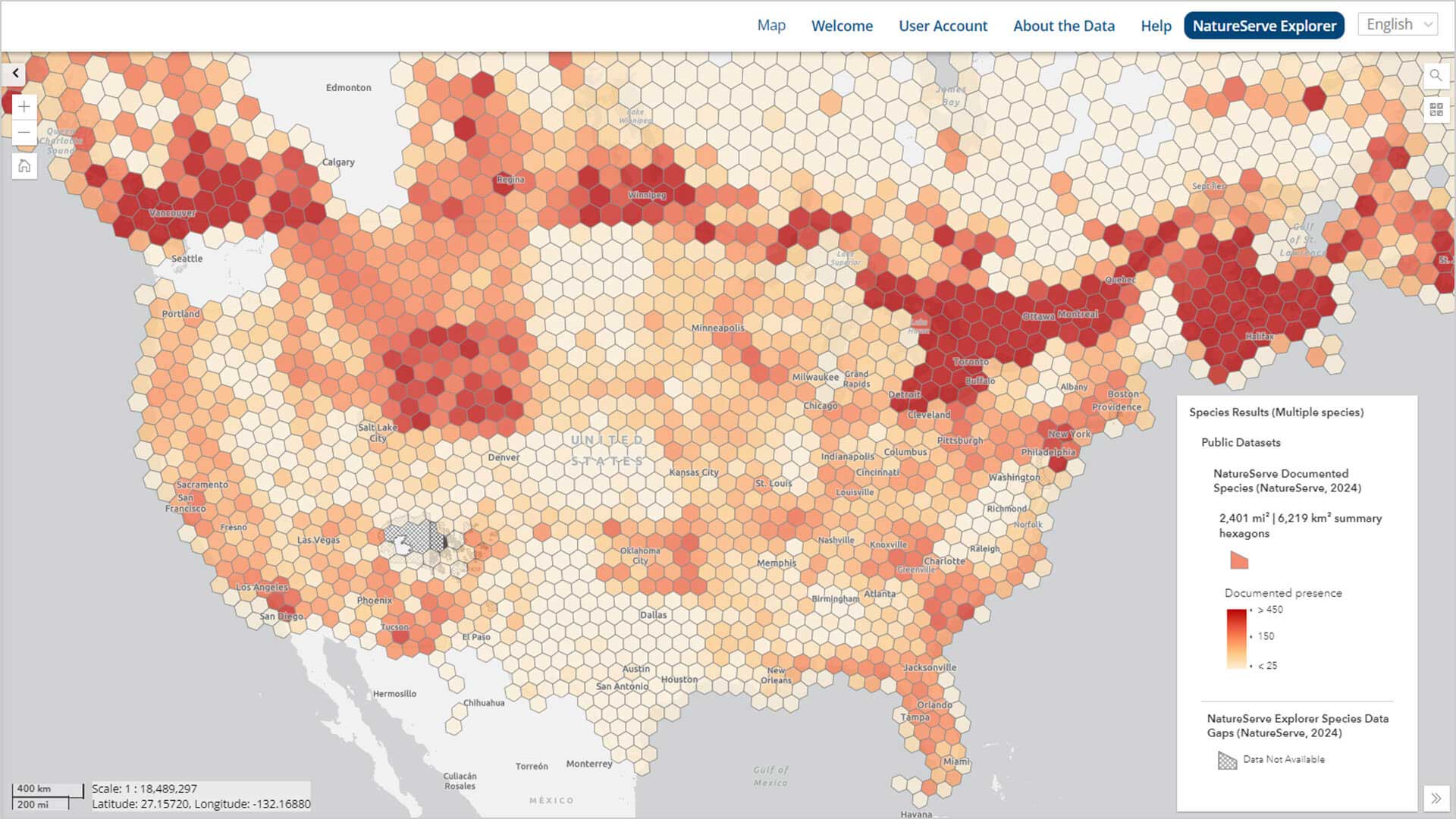

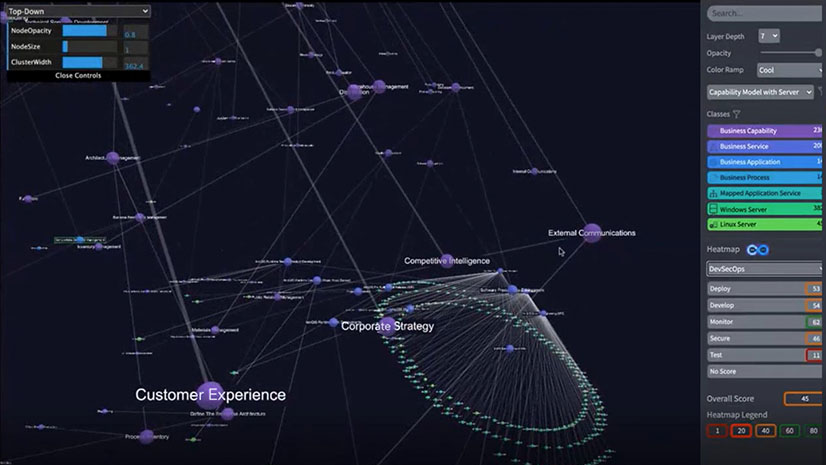

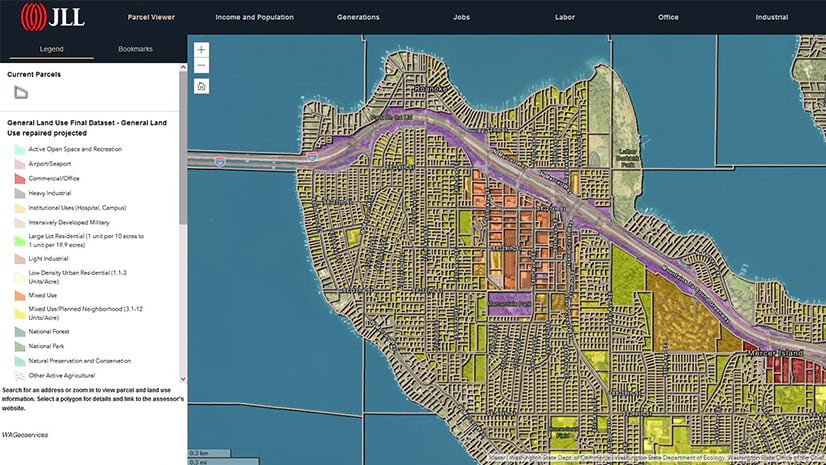

The heart of NatureServe Explorer Pro is a web-based interactive map, powered by geographic information system (GIS) technology, that allows users to access data about rare and endangered species and ecosystems throughout North America. Users can specify a single species, like a forest bat or blackbanded sunfish, and see its distribution across state and provincial lines.

Alternately, a forestry company can select or draw an area of interest to generate a regional biodiversity report—an analysis increasingly important to corporate boards and regulators. Companies in mining, agriculture, energy, and construction have already begun using the tool.

A Rising Demand for Tools to Measure Ecosystem Impacts

The NatureServe Explorer Pro tool, launched in April 2024, arrives as companies are gaining a new awareness of the business risks of nature loss. Regulatory frameworks such as the European Green Deal and the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) are adding pressure on businesses to evaluate how their operations impact ecosystem health.

Demonstrating that a company is “nature positive”—or helping to reverse biodiversity loss—can be challenging. Explorer Pro is one of the first tools to harness data about plant and animal species and ecosystems on a local and national level, drawing on data gathered by over 60 governmental and nongovernmental programs.

NatureServe’s mission-driven culture and deep familiarity with the power of location technology helped the small nonprofit accomplish this ambitious task.

“Everything that NatureServe does, GIS underlies that,” says Regan Smyth, vice president for conservation science at NatureServe. “It underlies our whole data management system, the analysis, our predictive habitat models. GIS technology is what lets a 60-person nonprofit run a biodiversity informatics network that serves North America.”

The Evolution of a Flagship Biodiversity Organization

NatureServe’s roots trace back to the 1970s, when the US Endangered Species Act spurred the creation of state natural heritage programs to document biological diversity. NatureServe became a hub for those network data providers, employing GIS to centralize and organize biodiversity data.

Prior to the launch of Explorer Pro, NatureServe’s main public offering was Explorer, an open-access database providing information on 100,000 species and ecosystems. Starting around 2019, NatureServe’s leaders saw the need for a geographically sophisticated upgrade that would draw attention to their capacious biodiversity resources.

“We wanted people to know about the best quality biodiversity information that exists in North America, and we felt strongly that providing access to that online would allow the data to have maximum impact,” Smyth says. A map was the way to do it.

From Grand Ideas to Dogged Work, NatureServe Explorer Pro Takes Shape

A 2020 product visioning exercise launched NatureServe Explorer Pro’s development, with leaders aligning the tool’s designs with clients’ needs.

“There were definitely ideas about what Explorer Pro was desired to be,” says Margaret Woo, senior software designer at NatureServe. “But there were a lot of hurdles that we had to overcome.”

One of the major challenges NatureServe faced was getting its data providers—the state agencies and universities that catalog species data, known as the NatureServe Network—to agree on what could be shared publicly. Lori Scott, NatureServe’s chief information officer at the time, solicited input from the NatureServe Network and other stakeholders including scientists, corporate clients, and software developers.

As NatureServe moved from ideation to execution, principal software engineer David Hauver and Woo helped find the line between the imagined and the feasible.

Woo abides by a development philosophy of economizing effort and time—summed up in her mantra, “stop wasting time doing dumb stuff.” She also believes in making user interfaces as intuitive as possible.

“Whenever we develop anything and it comes with 17 pages of instruction,” Woo says, “we have not done our jobs.”

Incorporating GIS into the app provided users an easy way to interact with complex data. Consultations with forestry industry clients led to the addition of a simple but powerful GIS capability: a company can drop a point on a map and gather biodiversity data from a radius of hundreds of miles around it.

A Complex Project Gains Clarity

Explorer Pro’s shape continued to come into focus throughout 2021. Smyth would create slide decks of potential features for the tool, while Hauver and his team built wireframes for product design. Development followed.

Every few weeks, the software team held sprint reviews revealing the latest updates to NatureServe staffers.

“Those meetings were a ton of fun,” Smyth recalls with a smile. “So many times, I’ve just [thought], ‘Wow…I had this thing in my PowerPoint and now it’s come to life and it’s even better!”

The meetings often introduced new wrinkles or challenges for developers, as the organization figured out how to present scientific information accurately and deal with data access issues.

For Woo, the vision of the project clicked while she was on a nature walk with the organization’s then CEO. He pulled out his phone and showed her mobile apps like iNaturalist’s Seek, which allows a user to point a camera and automatically identify plants and animals.

The moment helped clarify the ambition of Explorer Pro: to provide both authoritative data and a seamless user experience.

Smyth experienced a breakthrough when she saw the first demo featuring habitat models. “Having that all in one place was amazing to see,” she says.

Later, previewing the tool for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2023, Smyth recalls the pride she felt when she realized, “Hey, we are public now.”

Bringing Better Visibility to Nature Through Maps

After piloting Explorer Pro with several companies and organizations and building a portal for partners to submit data, NatureServe undertook its full public launch in April 2024. Anyone can log in and use the tool without any technical background. At the same time, licensed users like businesses can pay to access more granular data as well as a geodata portal to download information directly. Everyone can interact with biodiversity data on maps.

“It’s taking advantage of the democratization of spatial information that comes with these online GIS tools,” Smyth says, “but also supporting a pretty sophisticated user group that requires additional functionality.”

Over 8,700 users have registered for Explorer Pro. It’s a new level of visibility—both for NatureServe and the species the nonprofit seeks to protect and preserve.

That accomplishment—and the collective effort that brought the app to life—gives Smyth great satisfaction.

“As an organization I think we’ve been a little hidden,” she says. “With the release of this tool, I think we’re empowered to have more of an impact…and meet some of the demands of the moment to more effectively manage biodiversity.”

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

November 12, 2018 |

February 1, 2022 |

July 29, 2025 |

July 14, 2025 |