Before the COVID-19 pandemic transformed commerce and social norms, state and local governments across the United States were grappling with a trend toward cashless businesses. Some business owners saw cashless transactions as the way of the future—a more efficient way to conduct commerce. Some city councils and state legislatures feared cashless businesses would exclude significant portions of the population; namely, those who could not access digital payment methods and those without the inclination to do so.

The tension between these two perspectives may grow in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak. Legislators and business leaders will face the sobering reality that societal inequalities created devastating COVID-19 outcomes for certain vulnerable populations, and that many of those populations also fall outside traditional banking channels, leaving them unable to access the credit or debit cards needed for cashless transactions.

Meanwhile, the spread of coronavirus has underscored the danger of hand-to-hand interaction of all kinds. Contactless, cashless transactions now seem like a necessary defense against a health threat, not just a convenient feature of commerce.

As those views evolve, it’s worth examining where we left off before the pandemic.

Laws Aim for Protection

In January, the New York City Council passed a bill requiring businesses to accept cash. In many instances, visitors to city stores and restaurants had no choice but to pay with a card since cash was not accepted. The NYC decision followed bans on cashless businesses in New Jersey, Connecticut, Philadelphia, and San Francisco last year.

New York City’s reasoning echoed Massachusetts’s decision to ban cashless businesses starting in 1978—citing discrimination against those who don’t have a bank account or access to credit. Since then, objections to electronic-only transactions have expanded, with some detractors philosophically opposed to credit and others fearing data and identity theft.

The move frustrates businesses that have seen efficiency rise as cash-free transactions eliminate the tedious and time-consuming tasks of counting change and balancing cash drawers. Retailers also like cashless stores because robbers can’t grab cash and threaten employee and customer safety, and human error in handling transactions is reduced. Now they’ve added health and well being to the list of benefits.

Still, before COVID-19, legislation against cashless shops was on the rise in cities and states. Businesses with an eye on inclusion can appreciate balancing efficiency with access for all customers.

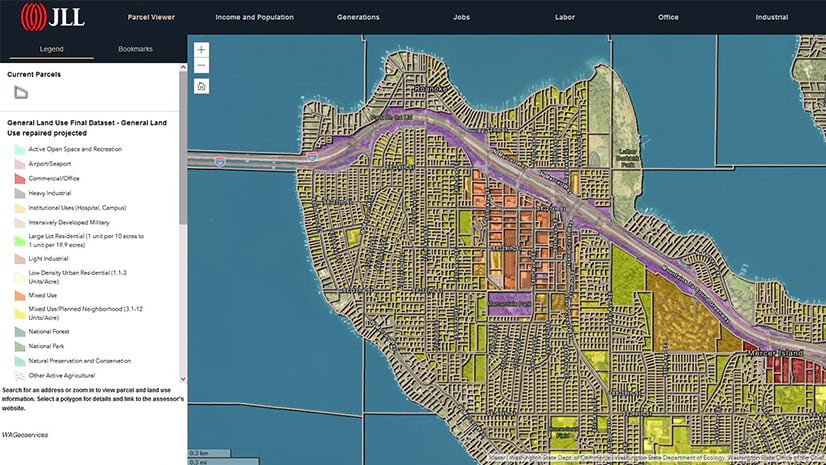

Given the localized nature of these policies, businesses that already use location technology for initiatives like market development can now use it to devise strategies that account for customer preferences for cash or card—and perhaps find alternatives that blend both options while protecting the public.

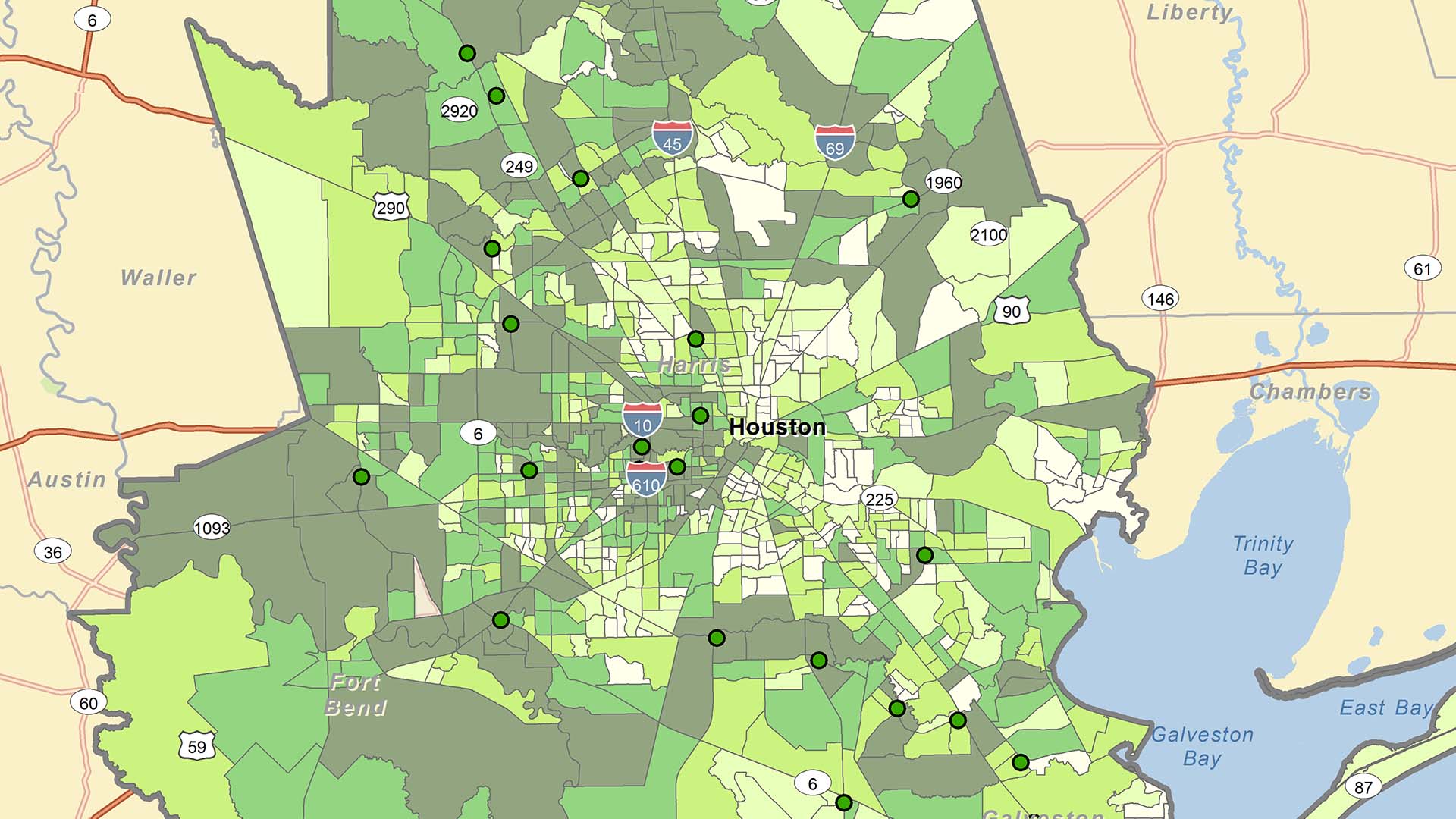

This geographic information system (GIS)-based smart map delivers insight on this consumer phenomenon, helping business leaders understand community preferences and make strategic decisions.

Data to Guide Policy Decisions

Prior to the New York City Council decision, the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA) analyzed the household finances of city residents and determined that more than 11 percent of New Yorkers don’t have access to a bank account or credit card. Roughly one million households, one in four, are considered unbanked or underbanked, meaning they don’t have a checking or savings account, or they do but rely on places other than a bank to cash checks or transfer money.

The DCA study was conducted by the Urban Institute, which used GIS technology to perform the location analysis. The institute found striking banking differences in New York’s five boroughs, revealing that people in the Bronx and Brooklyn have the least access to banks.

In an earlier study, DCA found that people in the neighborhoods of Melrose in the Bronx and Jamaica in Queens spent $19 million in check cashing fees annually. For the unbanked, a typical fee of $15 to cash a $100 check amounts to an annual percentage rate of roughly 400 percent.

With that location and demographic data in focus, DCA weighed in favor of banning cashless businesses, and even suggested the council go a step further. DCA advised creating more outreach to improve financial inclusion in the city, including bank and financial tools to help more residents build a secure financial future. In the wake of COVID-19, officials might consider expanding that effort to investigate how to blend the goals of financial inclusion and public safety.

Retailers on the Move

Two restaurant chains headquartered in New York City, Dig Inn and Dos Toros, were among those that went cashless prior to the ban. Sweetgreen, another company that does business in the city, says its cashless strategy sped transactions by 15 percent. Each company commented during New York City’s public hearings. Now that the ban has passed, all have expressed a willingness to go back to cash, but some have vowed a 10 percent price increase to cover efficiency losses.

Dos Toros was among the most vocal businesses during the hearings. Cofounder Leo Kremer said that two of the restaurant’s locations were robbed prior to going cashless, and that none have been since, according to a story in Skift Table. The chain shared plans to expand in cities that don’t mandate a cash and debit/credit payment system.

In a time of rapidly evolving monetary systems that includes digital currency like Bitcoin and tap-and-pay systems like Apple Pay, retail executives must carefully weigh the costs and benefits of additional systems. Cities and states that don’t allow cashless businesses could see automated retailers—such as the cashless and cashierless Amazon Go—pass them by.

Globally, the number of bank notes in circulation has been falling in most countries—along with ATMs and bank branches. In Sweden, just 2 percent of transactions involved cash as of 2016. In contrast, banknote-based transactions outnumbered digital mechanisms in most developing countries. As cash and cashless systems continue to vie for dominance around the globe–particularly in the post-COVID-19 world—the ability for businesses to map and monitor changes in related legislation will be key to business planning and market development.

For some executives, scrutiny of business transactions represents a frustrating tug-of-war between the past and the frictionless future promised by mobile technologies. For others, the debate has brought financial inclusivity into strategic discussions. Among forward-leaning executives, the original question of convenience has evolved into a deeper awareness of those left behind, and an exploration of the business opportunities available in serving them. In all cases, a clearer understanding of people, place, and policy helps guide key business decisions.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

November 12, 2018 |

July 25, 2023 |

February 1, 2022 |

July 29, 2025 |

August 5, 2025 | Multiple Authors |