Not only is there no such thing as a free lunch—it’s more expensive than you think.

We know this because of a practice called true cost accounting, which puts a price tag on food’s environmental toll and may be nearing a breakout moment in the business world.

As a recent New York Times article explained, beef that costs $5 per pound in the supermarket has a true cost of $22. The extra $17 is mostly the toll for ecosystem damage caused by cattle farming. Other costs measured by true cost accounting include water stress, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions.

A thorough assessment of true cost involves more than just dollar figures. It starts with an understanding of where products come from and how much value nature provides to a given location.

If true cost accounting finds its place in purchase decisions and regulatory frameworks, transparency and operational visibility into the supply chain will be essential. A geographic approach to operations will help businesses adapt.

Regulatory Compliance and True Cost Accounting

True cost accounting is not a new concept. A 2021 Rockefeller Foundation report pegged the true cost of food in the US at three times the $1.1 trillion Americans spend on it annually.

Recently, the theory has begun to move into practice:

- A German supermarket chain now applies true cost accounting when setting prices on select products.

- A coffee house in the Netherlands partnered with the Dutch government and private vendors to charge “real prices” reflecting hidden environmental and social costs.

- In the UK, the Ministry of Agriculture, four supermarket chains, and the National Farmers Union have collaborated to develop the global farm metric, a data-based measurement of food inputs and impacts.

Governments are now considering true cost accounting—or elements of it—in regulatory and purchasing decisions. Denmark levies a tax on methane gas emitted by some farm animals. The state of New York may soon direct its agencies to use true cost accounting for food procurement decisions, including with school lunch vendors.

Companies involved in all stages of production, from growing and processing to transport and retail, will feel the ripple effects of these decisions. New York’s state agencies alone account for one out of every thousand dollars spent on food in the US.

Mapping Cost in Tiers

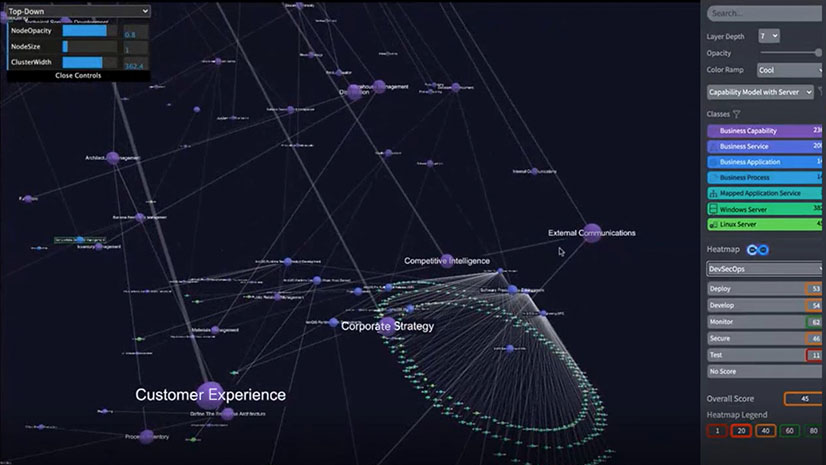

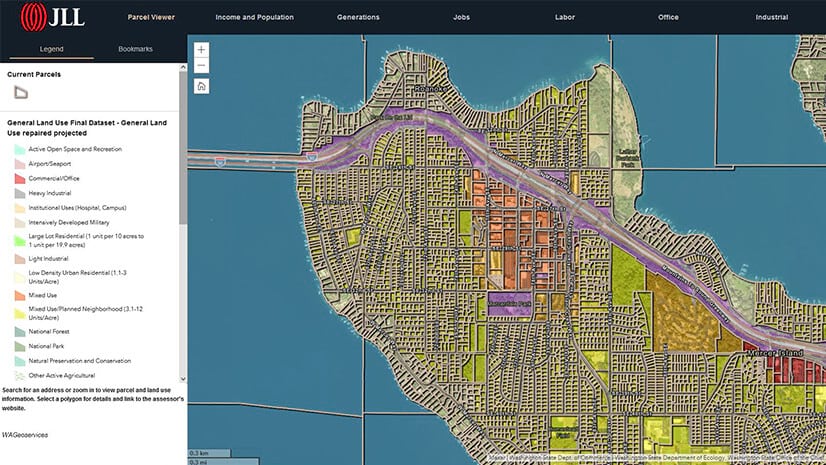

Already, companies routinely create digital basemaps of their operations, using geographic information system (GIS) technology. A GIS map can include multiple data layers, each detailing variables affecting the true cost of a product. By showing where costs are incurred, companies gain a better understanding of how they accrue.

Consider a company that sells tomato-based products like ketchup and pasta sauce. To assess products’ true costs, analysts might gather data on how much water each supplier farm uses, along with their rates of fertilizer or pesticides and the emissions generated by trucks during distribution.

Those maps, featured on a GIS dashboard, give executives, product managers, pricing analysts, sustainability teams, and compliance managers a new level of product accounting.

Computing the True Costs of Development

True cost accounting aims to measure the environmental impacts—such as deforestation, water stress, emissions, and species loss—of activities like mining, construction, and food production. It’s part of a broader movement.

A new UK law requires that all new building projects not only preserve existing biodiversity, but demonstrate a 10 percent net gain. Meeting those requirements means understanding the natural conditions in specific locations and measuring progress over time.

Maps have been key to visualizing sustainability goals in similar scenarios. A massive development project in Vienna, for example, uses a GIS-based digital twin to ensure that the construction process adheres to climate-related requirements.

Across a range of industries—from infrastructure development to manufacturing to agriculture—companies are facing calls to quantify their footprint on the natural world. True cost accounting is the latest practice to demand this kind of location awareness, but with climate change in focus, it’s unlikely to be the last.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

April 29, 2025 |

November 12, 2018 |

February 1, 2022 |

May 6, 2025 |