We’ve had a few smaller incidents since this storm. Now, when disaster strikes we have a system in place to collect the data, back it up on our servers, and when the response effort is over, refresh and re-publish the service via the cloud.

September 1, 2017

Imagine the impact of watching storm clouds gather, hearing tornado sirens wail, scrambling to your basement, and having to listen to powerful winds tear your home apart.

As the storm fades, an unnatural quiet prevails as you pick your way out of your refuge to find your roof gone, walls toppled, and your yard littered with pieces of your house and belongings. You stare at where your living room wall once stood, wondering where the portraits of your family have gone, and watch as the furniture that remains gets slowly soaked by rain.

As you stumble through the splinters, you can’t help but wonder, “why?”

“What is supposed to happen, will happen,” was what Refujio Luevano told reporters from the local Morris Herald-News after the second tornado swept through his community within a span of 18 months.

That’s a remarkably composed attitude from the only man to have his home hit by both storms.

Assessing impacts

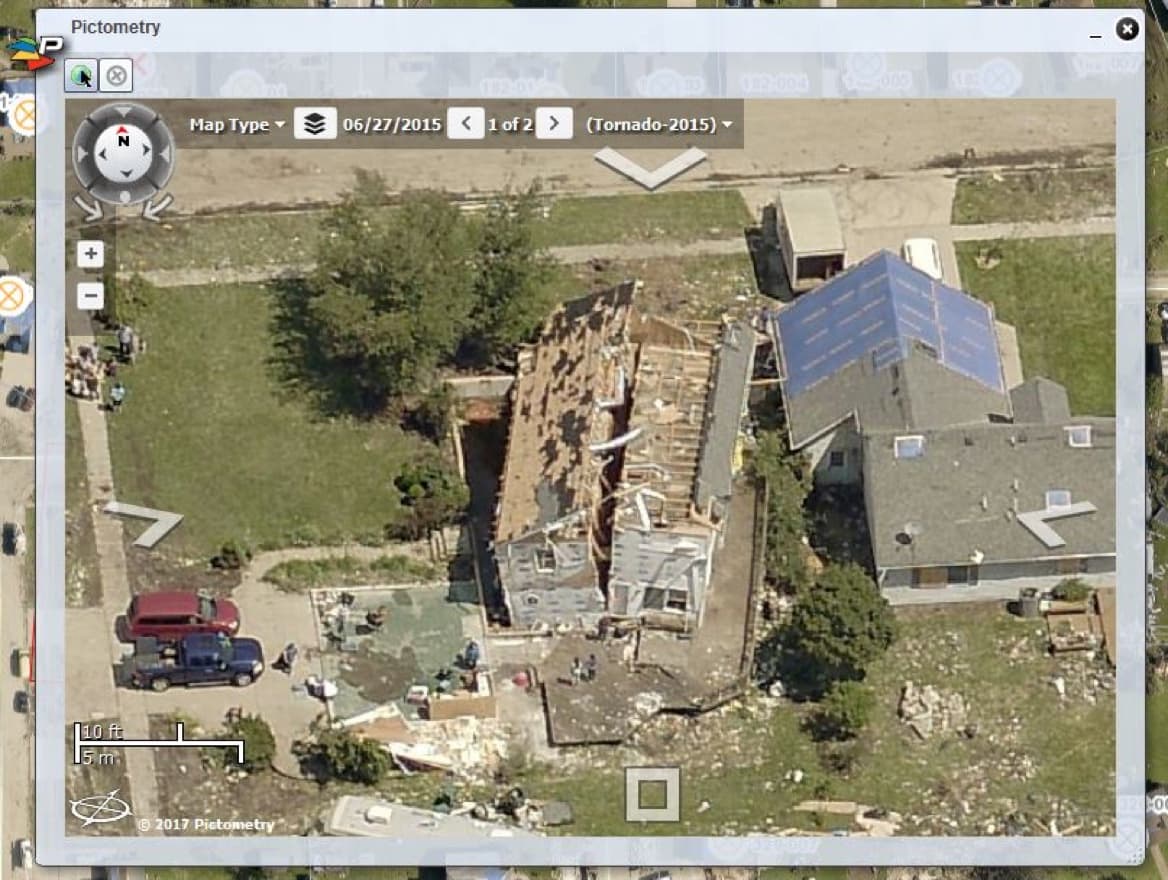

The neighboring towns of Coal City and Diamond in Grundy County, Illinois experienced this unfortunate repeat calamity. A tornado struck the Village of Diamond on Nov. 17, 2013, damaging 207 homes. A stronger tornado hit the Village of Coal City on June 22, 2015, damaging more than 880 homes and businesses.

After any storm, first responders quickly converge to make sure everyone is okay and to secure the area against theft. Damage assessments come next, as they are used to allocate necessary resources and provide a lasting record of the aftermath.

“When performing a damage assessment, it’s always best to do it as soon as possible following a disaster, when the damage is fresh and residents are most likely home cleaning up,” said Dave Ostrander, geographic information system (GIS) director for the County of Grundy. “That way we can quickly retrieve the basic information required by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and get on to cleanup, community outreach, and the coordination of services.”

The goal is to make timely and thorough assessments, limiting the intrusion, and the painful questions that force homeowners to take stock of what they have lost.

The county is the first in the chain of command, reporting to the state, which reports to the FEMA. The ability to capture data quickly at the county level translates into more rapid assistance from state and federal agencies, and aligned nonprofits. It also answers the immediate requests from the media for hard numbers about the storm’s impact.

App efficiency

In 2013, Ostrander had been working on a mobile damage assessment tool just prior to the first tornado. As the central person to apply GIS, his job revolves around maps and their ability to create two-way communication channels between the office and workers out in the field.

He configured Collector for ArcGIS, an application that can be deployed to handhelds with a map interface to capture the data FEMA requires. The application can mirror FEMA’s damage assessment form, allowing each individual to check boxes and take pictures on their phone or tablet that can be centrally compiled to improve the speed, accuracy, and consistency of damage reporting.

“We tried it out, but it was a bit of a headache, because the devices being used relied on mobile hotspots that were decidedly inaccurate at pinpointing user locations,” said Ostrander. “Secondly, staff had never used the app before, and it’s never ideal to rollout something new during the chaos of an ongoing incident.”

In the end, the application proved secondary to the more traditional ways of gathering information using paper and pen.

The damage from the 2015 storm was ten times the size of the first storm as it hit Coal City squarely during the evening hours of June 22nd. That night at the Grundy County Operations Center, Ostrander again presented the application to the disaster response personnel. He accompanied the EMA staff early the next morning with the application in hand.

“When I got to ground zero, I pulled up the damage assessment app on my tablet to perform the initial test, and immediately noticed I had a major problem. The area’s cell network had been severely damaged by the storm to the point that data collected could not be uploaded using the app,” said Ostrander.

Running back to the office, Ostrander worked to troubleshoot the application. A quick call to Esri helped him get past a hurdle, pushing his data to ArcGIS Online, a mapping platform that uses distributed computers, commonly referred to as the cloud.

“Hosting this kind of mission-critical data in the cloud seems glaringly obvious now, but during the design phase it wasn’t something I had completely considered,” said Ostrander. “What good is a damage assessment app if the data it relies on to function is stored on premise, and the office building is destroyed?”

Proof point

When Ostrander returned to report back to the EMA director, he was arriving just as a busload of 30 volunteers were being briefed. They were given blank FEMA damage assessment forms and told to take pictures.

“As I stood on the outskirts of the group, I felt foiled again,” said Ostrander. “It was an odd spot to be in as I was acutely aware that our app provided the most efficient collection method but I also knew I was once again simply too late to get everyone on board.”

Rather than give up on the opportunity to showcase the app’s potential, he teamed with the Grundy County Assessor to test out the app’s capabilities under the real world duress of a full scale natural disaster.

The parallel effort was a good no-pressure test. Ostrander and the assessor proceeded to take pictures of each home, and to run through a series of check boxes on the app. With maps and aerial photos of the towns on the app, they could accurately pinpoint each property even if the home was destroyed and any indication of the address was gone.

The two-person team captured 40 homes per hour, compared to an average pace of 12 homes per hour by the paper-based team. With their larger numbers, the volunteers were done in a day while the app team completed their work in two. However, additional days were needed to digitize the paper data, decipher each individual’s notes, and to collate photos.

“We uploaded our data every hour and shared it with the Illinois emergency operations center in Springfield simply using a link,” said Ostrander. “In contrast, the larger team had a stack of paper and hundreds of pictures, which required required time and effort to make similarly accessible.”

Grundy County’s 2015 response marked the first time a mobile damage assessment application was used in the State of Illinois. The data was directly consumed and shared with all agencies involved, which greatly sped awareness of the damage and delivery of services to those impacted.

We’ve had a few smaller incidents since this storm. Now, when disaster strikes we have a system in place to collect the data, back it up on our servers, and when the response effort is over, refresh and re-publish the service via the cloud.

Easing pain

Returning to Refujio Luevano, the unlucky homeowner that was hit by both tornadoes.

“It’s just money,” he says. “Life, you only have one.”

Luevano learned that it’s best not to take the impact too personally. Things can be replaced, and bonds of family and community are what get us through our hardships.

It can be hard to recover, however, and reminders can be painful. The county tax assessor needs to update their records so they don’t send the same tax bill to a property owner who suffered a complete loss.

Using the collected damage assessment data taken from the ground, along with imagery captured shortly after the storm, a clear picture of the impact can be easily visualized. Aerial photos from before and after the storm provide the proof needed to make fair tax adjustments.

The lessons learned on this disaster are leading to further collaboration across Grundy County departments. Template-based GIS applications are fueling a wide range of government service solutions. At the state level, discussions have begun to put together a similar damage assessment application in the Go-Kit for use if disaster strikes counties that don’t already have a damage assessment solution.

“We’ve had a few smaller incidents since this storm,” said Ostrander. “Now, when disaster strikes we have a system in place to collect the data, back it up on our servers, and when the response effort is over, refresh and re-publish the service via the cloud. That way, we always remain ready to go, even though we’d obviously prefer never to use the damage assessment application.”

Esri’s Disaster Response Program provides software, data coordination, technical support, and other GIS assistance. Learn more about the Disaster Response Program or contact us in times of emergency.