January 14, 2025

A patchwork of salt evaporation ponds lines the South San Francisco Bay in vibrant greens, oranges, and blues, depending on the organisms that thrive at different salinity levels. The ponds, originally used for salt production, are now a focal point of the largest tidal wetland restoration on the West Coast.

The ambitious South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project will eventually transform 15,100 acres of industrial salt ponds back into tidal marshes and other wetlands, while adding recreation areas and providing flood risk management. A group of government agencies, municipalities, and researchers are partners in the effort, including the California State Coastal Conservancy, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Coordination is important with so many experts involved and a project scope roughly the size of Manhattan. Geography serves as their common language.

Maps made with geographic information system (GIS) technology combine the data layers of Bay Area restoration projects into a visual resource. Meanwhile, project managers record milestones in a GIS portal. The technology also supports planning and analysis, as ideas and decisions can be vetted virtually to understand potential impacts on the ecosystem.

Currently in the second of three phases, the effort is critical to the long-term health of the San Francisco Bay, which has reached a tipping point as human impacts threaten its natural balance.

“Over the last 150 years, the San Francisco Bay has lost about 80 to 90 percent of its wetlands. Restoring tidal marshes in that area will be a line of defense against sea level rise and climate change,” said Donna Ball, the project’s lead scientist and senior scientist at San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI). A partner in the project, SFEI is an environmental research institute and nonprofit organization that has been using science to rebuild and sustain the health and resilience of the San Francisco Bay since the early 1990s.

The San Francisco Bay, the largest estuary on the West Coast, protects over 90 animal and plant species listed as threatened or endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act.

Commercial salt production hindered its biodiversity. Some microorganisms can thrive in the ponds. But broader diversity is limited by each species’ ability to tolerate high levels of salinity, which can harm plant growth, alter soil composition, destroy natural vegetation, and change the wetlands’ ecological health.

Alternately, tidal marshes provide an array of vital ecosystem services that mitigate the effects of climate change. Marshes naturally filter water, capture and store carbon dioxide, stabilize shorelines, and provide a buffer against sea level rise and flooding by slowing down stormwater and runoff. They also provide a habitat for a range of species, such as the salt marsh harvest mouse and the Ridgway’s Rail, a hen-sized marsh bird only found in the San Francisco estuary.

“For us, that’s the goal,” Ball said. “To create wetlands that are used by the species that need it.”

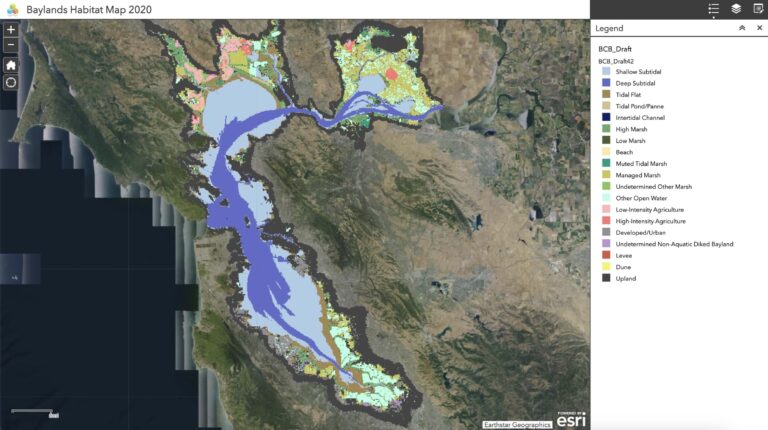

Scientists use maps to understand this complex landscape. In April, SFEI released a new version of the Baylands Habitat Map to aid in protection and restoration efforts.

The map reveals changes over the past two decades. It includes information about how land use and infrastructure affect restoration and management opportunities. SFEI plans to update the map with new imagery and data every five years to understand habitat changes. This knowledge will be integral to monitoring project outcomes.

“One of the things we need to track is the evolution of habitats,” Ball said. “As we restore habitats, we need to be able to see how they’re developing. We’ve been doing mapping every 10 years. But the Baylands Habitat Map is a really promising tool for us because we’ll be able to see their evolution on a quicker time frame.”

As the project progresses, the ponds’ berms and levees—raised structures used to mitigate flooding—are broken down to restore their historic connection to the rest of the Bay. Some of these areas will be restored naturally to tidal marshes on their own in 10 to 15 years. Other ponds may need more sediment to correct elevation levels. Scientists will continually monitor ecological markers to ensure the project successfully meets restoration goals.

SFEI’s research reports, which are filled with maps and drone imagery, are integral. A report from the Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals Project, for example, identified the importance of building and restoring upland transition zones in marshes, which act as buffers to sea level rise.

As restoration projects increase, so does the demand for sediment—it’s unlikely that the Bay’s natural supply can fulfill the needs of every project. The Sediment for Survival report outlines alternative sources of sediment and helps the project’s scientists understand its ecological role.

A science-based path to resilience emerges when these habitat and sediment resources are used in tandem. “We’re building efficiencies to be data-driven with the way that we’re approaching our techniques and our metrics,” said Alex Braud, a GIS specialist and environmental scientist at SFEI. “When projects need to be prioritized, having information at this scale gives you context to make better decisions and be efficient with your resources, whether that be funding, sediment, or time.”

The Baylands Habitat Map is integrated with SFEI’s EcoAtlas, an online tool that provides access to information about the distribution, abundance, and conditions of California’s aquatic resources.

“The overarching goal of the EcoAtlas toolset is answering questions such as: Where are our wetlands? How are they doing? And what projects are restoring or impacting them?” said Cristina Grosso, managing director of the SFEI Environmental Informatics Program.

Each pond’s progress is tracked in the EcoAtlas. This resource, crucial for the restoration project, requires input and collaboration from dozens of federal, state, and local decision-makers.

Like much of SFEI’s work, EcoAtlas uses the Environmental Protection Agency’s three-level Wetlands Monitoring and Assessment framework, which emphasizes a geographic approach to conservation.

Wetlands function as part of larger ecosystems. GIS gives spatial context to these natural relationships and reveals priority areas for restoration.

EcoAtlas layers more than two dozen authoritative datasets on top of each other so that users can see how features such as vegetation, species diversity, and soil conditions interact with each other. With this comprehensive picture, scientists and project stakeholders can make informed decisions to benefit the Bay and the people who live nearby.

By cataloging California’s conservation projects and maps in EcoAtlas, SFEI and its partners facilitate future restoration efforts. As local governments and other organizations take steps toward climate resilience, they can use the portal’s research and findings to guide their paths.

“Some decision-makers want a pie chart with the overview of acres of wetlands, and data scientists really want to download the information. There’s a breadth of information summarized in EcoAtlas for different audiences,” Grosso said.

Learn more about how GIS informs climate action strategies for adaptation and mitigation.