January 5, 2021

Rapid growth in the number of dams along the Mekong River is transforming Southeast Asia’s energy, food, transportation, security, and ecological networks. Eleven hydropower dams now span the river’s mainstream before it leaves China, with hundreds more dams planned or under construction in the other countries that contain parts of this vital watershed. The development has been rapid, and the consequences to people and the environment are still largely unknown.

Scientists at the Stimson Center, a think tank focused on enhancing international peace, have been monitoring the hydroelectric power projects in terms of impact on regional stability and the food-water-security nexus.

“Our core message is that non-hydropower renewable energy, like solar and wind, can replace hydropower with far less disruption,” said Brian Eyler, director–Southeast Asia at the Stimson Center. “Our static map of Mekong mainstream dams is very popular for use in the media and for research presentations, but we realized that a static map didn’t show the full picture.”

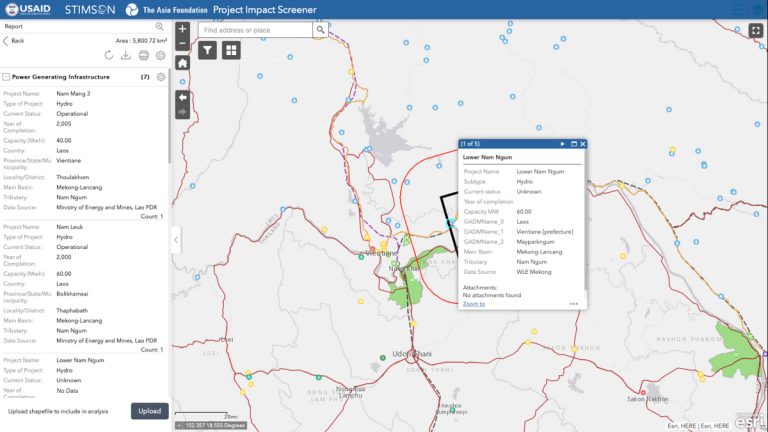

With support from US Agency for International Development (USAID) and The Asia Foundation through the five-year Mekong Safeguards activity, Eyler and his team set out to create the Mekong Infrastructure Tracker, a database of visual presentations, spatial analyses, and shared expertise. The dashboard was created using a geographic information system (GIS), with help from Esri partner Blue Raster.

“In addition to tracking dams, we had the idea to track solar projects after seeing a big uptick in the region in 2018,” Eyler said. “Our partners at USAID asked us if we’d track all infrastructure in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam. It didn’t take much consideration to jump at this opportunity because infrastructure is a hot issue in the Mekong region.”

The tracker catalogs projects for power generation and industrial development as well as road, rail, and waterway transportation. It also includes tools to analyze and quantify the impacts of infrastructure projects.

Construction on the existing dams has already displaced thousands of people, causing immediate impact for some people. Other river people who subsist on fishing and riverbank agriculture, are feeling effects of the ecological damage to the ecosystems. In the village of Baan Huay Luek in northern Thailand, for example, villagers speak about how the dams have switched the rules of nature, with dry seasons no longer dry and wet seasons no longer wet.

The Mekong River starts on the Tibetan Plateau in China and flows through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam before emptying into the South China Sea. The river has been deemed Southeast Asia’s most important waterway as it is central to the lives and livelihoods of millions of people and serves as a food source. The Mekong watershed is known as the “rice bowl” of Asia, and 20 percent of the world’s freshwater fish catch comes from its waters.

To date, governments and activists interested in Mekong watershed development have had to contend with the lack of information about or awareness of existing or planned projects.

“This information is usually something that private sector organizations collect and then distribute only to their clients,” said Regan Kwan, research associate at the Stimson Center and manager of the Mekong Infrastructure Tracker project. “Through GIS, we make the data available so that anyone can visualize it, analyze it, and contribute to it.”

The Stimson Center works with a wide range of stakeholders on this and other projects, with an eye on community engagement and capacity building. The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker has drawn interest and participation from national development banks, government agencies, ministries, international nongovernmental organizations, local grassroots organizations, the private sector, academic researchers, and individuals.

“Our Stimson team is relatively small, and we’re collecting thousands of data points,” Kwan said. “We’re bound to make some mistakes, skip things, or not see everything others are seeing. It’s great to have others use our data, share their viewpoints, and fill in gaps.”

In addition to serving as a singular accurate data source, the Mekong Infrastructure Tracker helps guide foreign policy and assess investment opportunities.

“Having all this information transparently and freely available gives those looking to achieve a more sustainable future a resource to ask questions anytime they want,” Eyler said. “No one has provided this depth of information before.”

The Stimson Center avoids advocacy, instead allowing partners to draw their own conclusions from the data. One such partner—EarthRights International, based at the Mitharsuu Center in Chiang Mai, Thailand—trains young activists on development issues, environmental impacts, and human rights law and policy. During a seven-month program, called the EarthRights School, students take classes and learn to conduct research.

“We’ve been encouraging our students to use the Mekong Infrastructure Tracker to map out various projects in their home countries in order to support their advocacy,” said William “BJ” Schulte, Mekong policy and legal adviser, EarthRights International. “We value the Tracker as a strong tool that can support networks of activists and community leaders to address the regional energy strategy in the Mekong region as we see a growing reliance on fossil fuels, especially coal.”

One of the reasons fossil fuels are gaining interest in Cambodia, for example, is that existing dams haven’t produced as much energy as predicted, largely due to an ongoing drought. Coal causes grave concern because it releases the most greenhouse gas of any fuel, and the hazardous waste by-product coal ash is hard to safely store.

“One of our alumni alerted us to a coal-fired power plant that’s going to be sited within [Preah Monivong] Bokor National Park,” Schulte said. “We’re working with local activists to understand the local impacts.”

EarthRights International has participated in adding data from communities to the Mekong Infrastructure Tracker to raise awareness about such projects.

“The tracker gives us the ability to draw out where all the projects are and see how they impact each other,” said Naing Htoo, Mekong program director at EarthRights International. “We use it to see the regional perspective, including the financiers behind the projects, which includes a lot of cross-boundary investment.”

Many government leaders are seeing the Mekong Infrastructure Tracker data and getting a greater regional perspective.

“At first we had some anxiety about presenting our data to governments in the region, because satellite imagery and other forms of remote sensing data are often seen with suspicion,” Eyler said. “We found that data which shows the speed of change in the region and the ease of visualizing and analyzing the data appease concerns. It was the first time they could see what’s happening in other countries.”

China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative plays a major role in much of this development. The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker promotes awareness of this and other development programs.

“The data can be used to assess the geopolitics, seeing areas where China or other external investors from Japan, Korea, or the United States is more heavily invested,” Eyler said. “You can see how many projects are planned and how many are moving forward. Knowing the gaps is really useful information.”

With more infrastructure projects being planned, and with the rising risks due to climate change, EarthRights International workers are also seeing more negative impact on Indigenous people.

“Due to their locations, many of the large infrastructure projects disproportionately impact ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples,” Schulte said. “When they try to raise their voices, they are increasingly attacked or imprisoned, or even disappear. A lot of the fossil-fuel projects are backed by powerful people with significant financial interests.”

The transparency of the Mekong Infrastructure Tracker—along with the elements of citizen science that allow anyone to contribute—is encouraging widespread participation from a diverse array of people. The Stimson Center takes a data-accurate and research-agnostic approach to the platform to engage participants and encourage dialogue. Administrators are driven to gather complete data and present the truth.

“If anyone using our geodatabase realizes it differs from what they know about an infrastructure project, and they have sources to back it up, we provide an ArcGIS Survey123 form to fill in missing information,” Kwan said. “We review it, and if it checks out, we make the update.”

The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker has a Facebook group that participants use to drop links to news reports about infrastructure projects. If the news signals a new project, then it’s added to the database. Any information about changing timelines or project details are noted. In addition, hackathons are held to fill in data gaps and correct inaccuracies.

The dashboard focuses on five main datasets for energy, transportation, and water infrastructure projects, and has data about the surrounding environment as well as people, including ethnic groups. Data on energy projects—including biomass, coal, gas, geothermal, hydro, mixed fossil fuel, nuclear, oil, solar, waste, and wind—is curated along with transportation details on upgrades to canals, urban and high-speed railways, and national roads. The site also covers industrial development at airports, railway stations and sea or inland ports, as well as special economic zones that provide investment incentives.

“We work to ensure the data is accurate and complete,” Eyler said. “The vision is to continue to provide a mix of technical and simple-to-use tools to analyze the data and improve decision-making in the region.”

The Mekong Infrastructure Tracker database provides robust environmental and social impact indicator layers that allow anyone to see and study the risks and benefits of various development scenarios.

“A long-term goal is to create a scenario planning application which gives users a chance to generate their own investment scenarios and assess costs and benefits across a variety of indicators,” Eyler said. “Users could compare scenarios and even take their scenarios to other policymakers and planners to talk through multiple development pathways and choose the most optimal for their own locality or for the region at-large.”

Learn more about how location intelligence guides sustainable development.