The real benefit of this is engaging people in fire management and getting them thinking about their place, within the context of how fires burn.

January 23, 2024

A firefighter-turned-researcher is helping pioneer data-driven solutions to tackle today’s unprecedented wildfires.

Chris Dunn, assistant professor at Oregon State University’s College of Forestry, spent seven years fighting fires in Oregon and has seen the challenges firsthand. Firefighters must make urgent decisions with limited information. Often, they can only understand situations by physically entering dangerous scenarios.

As a firefighter, Dunn was full of questions. What if firefighters could already know the location and condition of all possible fire control points? What if they could predict the best places to catch each blaze? What if responses were already planned for most scenarios? What if mitigation efforts had already happened in the right places to ensure their success? What if they knew exactly when and where fires could be beneficial?

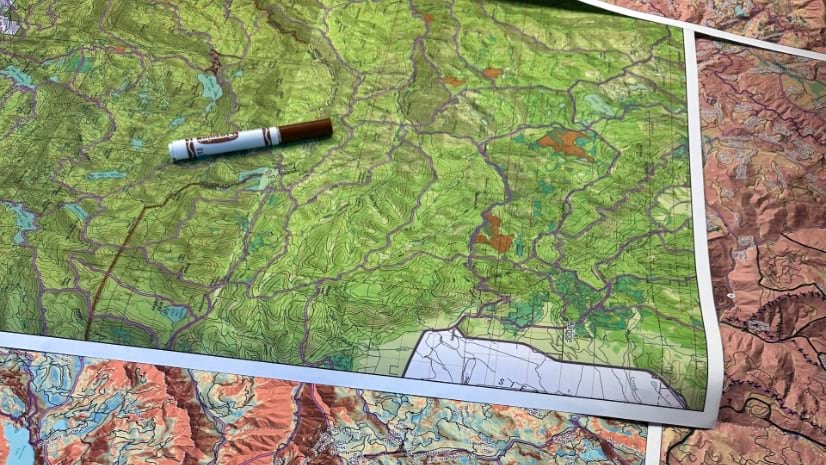

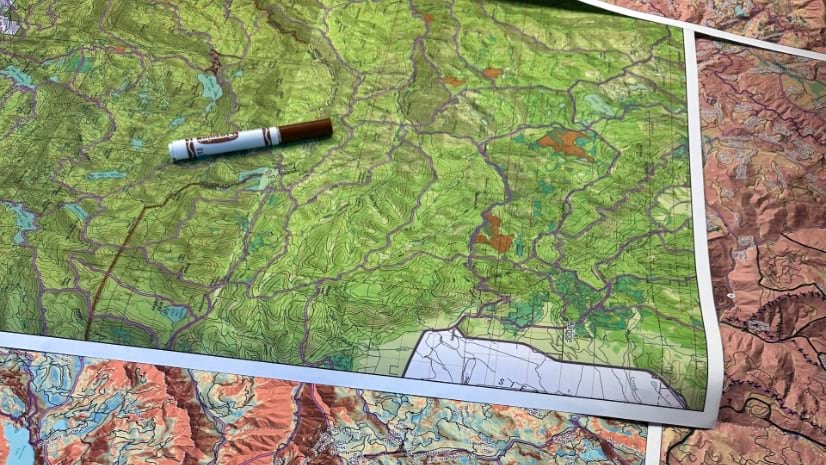

Today, the questions can now be answered using maps, geospatial analytics, and the power of collaboration.

Chris Dunn and colleagues from the US Forest Service’s Wildfire Risk Management Science Team at the Rocky Mountain Research Station are now using sophisticated mapping to give fire planners the information they need ahead of time. These tools are helping firefighters and communities come together to successfully manage fires.

The map-centric framework the team co-developed is known as PODs (Potential Operational Delineations). PODs are areas on a map whose border lines are human-made or natural fire-stopping boundaries such as roads, ridges, and water. PODs can range in size from a few hundred to thousands of acres.

The real benefit of this is engaging people in fire management and getting them thinking about their place, within the context of how fires burn.

These seemingly simple boundaries are built on a wealth of data. To create PODs, planners examine and divide the landscape for fire management, considering geographic features rather than property lines. Wherever a fire starts, a shared map shows which POD it’s inside of, and therefore the best places and opportunities to stop it.

PODs are built using geographic information system (GIS) technology, sophisticated mapping software that enables unlimited information about the relevant landscape to be included and analyzed.

Dunn first encountered GIS in the 1990s as an undergraduate. He realized that since fires occur in space and time, GIS technology could help him better understand and respond to them. He took one of the earliest programs offered in spatial information management systems and added it as a minor to his Forest Management degree at Colorado State University.

Now, Dunn combines his firefighting experience and GIS knowledge to develop and implement PODs. He uses GIS to simplify complex data for fire management, transforming it into something operational and useful.

Three main layers of data and analysis come together within GIS to give PODs their power.

These tools and data are the jumping-off point for starting a fire planning conversation using PODs. Next, planners need to enhance the data with local knowledge.

In developing PODs for a specific area, fire managers start by holding collaborative workshops with community leaders. They collaborate in person and online via GIS maps and other digital tools. In addition to data points such as risk assessment, control locations, and firefighting difficulty, the GIS maps show roads and trails, watershed boundaries, structure locations, and satellite imagery of the impacts of past fires.

Firefighters and land managers bring invaluable local knowledge and expertise to the table, much of it unwritten. The PODs workshops are a way of institutionalizing knowledge from fire experts so it can be easily shared and used by anyone who might need it.

“We blend the analytics with the local knowledge to make sure we’re not biased towards local knowledge and we’re not missing something in the analytics,” Dunn said. “You bring them together and you get the best outcome.”

This collaboration is critical because fires don’t recognize property lines or administrative boundaries. For example, the best place to stop a fire might be a road that runs through private property, so performing fuel reduction there might be crucial to future success. To create the best conditions for firefighters and the best outcomes for the public, people need to work together in shared stewardship of the land.

Dunn has found maps to be the clearest way to develop this common understanding of risks, management opportunities, and desired outcomes.

After initial workshops are completed, control points are verified in the field, POD boundaries are adjusted as needed, and any new information can be added to the shared map. Then PODs become operational—a springboard for action such as planning prescribed burns, allocating funding to harden boundaries, and communicating with any affected landowners.

Ashland, Oregon is one community working with Chris Dunn and the Forest Service to implement PODs. The valley community is surrounded by wildfire risk on all sides and narrowly escaped destruction during the Almeda Drive Fire in 2020. It’s also leading the way in data-driven fire mitigation and planning.

Dunn has worked with Ashland leaders to hold three PODs planning workshops, looking at the broader landscape of two million acres and refining a smaller area closest to the town. They prioritized protecting the municipal watershed and the town itself, paying special attention to the condition of boundaries most critical to those areas. Now they’re using that work to guide prescribed burns across Forest Service, municipal, and private forests, focusing on areas where initial fuel reduction has already been completed under the Ashland Forest Resiliency project.

According to Chris Chambers, Ashland Fire & Rescue’s Wildfire Division Chief, “We use PODs to help prioritize where we put prescribed burns on the landscape and where to plan future fuel treatments on private and municipal land. We won’t have enough money to do everything that we want to do everywhere, so it’s best to put our money in places where it’s going to matter the most.”

Ashland leaders are implementing PODs down to the community level in a very detailed way. Their level of collaboration is also unprecedented, with around 95 people involved. Having access to GIS technology has facilitated city leadership’s collaboration with private landowners and partner agencies to create a unified plan. “We need to come together, and the data and maps help us do that. Maps help show people why action is needed,” says Dunn.

As Dunn and his colleagues have been working to develop and test PODs, word has been spreading.

The data-driven approach and its proven success motivated US Forest Service leaders to champion the concept to the highest levels. Thanks to these advocates, $100 million in funding for PODs planning was explicitly embedded in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021, with an additional $500 million allocated to hardening PODs boundaries.

While Dunn is excited to see adoption in national parks and forests, he knows PODs also have the potential to transform the plight of fire-prone communities. He hopes to see the approach thoughtfully implemented everywhere in a wall-to-wall network of smart maps. And with GIS technology, virtually limitless data can be added to create a fully integrated system that supports fire managers in every phase of prevention, planning, and response.

“All of this is GIS. I wouldn’t do anything without it. Maps are the most effective communication tool to develop a truly functional strategy,” Dunn said.

Learn how firefighters and land managers use GIS to manage all phases of wildland fire.

See an overview of how the PODs planning process works in the US Forest Service video below.