August 18, 2020

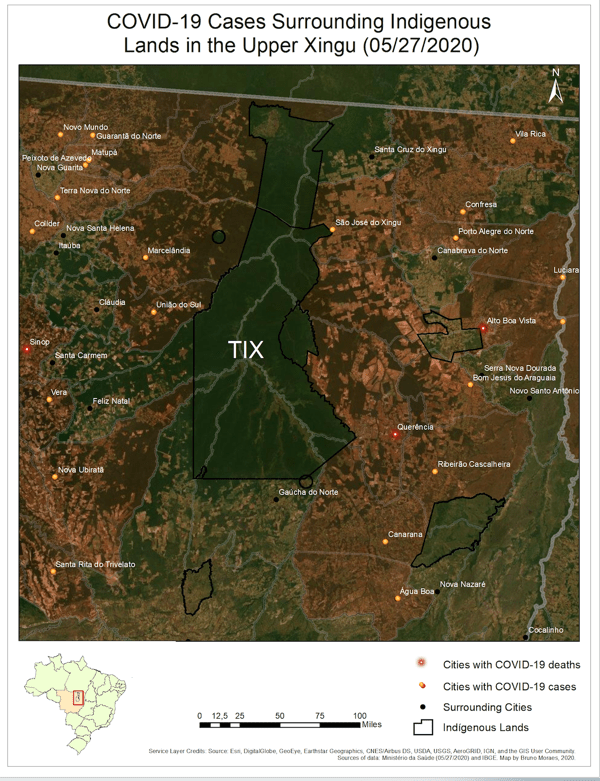

Hard hit by the pandemic, Brazil case totals are second only to the United States. The coronavirus has reached the remote regions of the Amazon rainforest where it threatens the very existence of vulnerable indigenous people.

Native communities have reason to be fearful, given that European diseases devastated their ancestors. Just as in other parts of the world, Brazil’s indigenous groups have proven more susceptible to the worst outcomes of COVID-19. They are also farthest away from medical care. As of late July, more than 15,500 indigenous Brazilians have been infected and more than 520 have died.

The Kuikuro people live in a remote part of the Amazon within Xingu National Park in Brazil’s Mato Grosso region. Before the virus hit, the tribe of roughly 330 people had embraced geographic information system (GIS) technology for community mapping—capturing connections to their land and safeguarding resources. Now, these same tools provide solutions to urge villagers to stay safe during the pandemic.

“The village now has its own COVID-19 dashboard to monitor who’s traveling,” said Michael Heckenberger, professor of Anthropology at the University of Florida. “The elders want to limit traffic but a lot of the younger members of the community think it’s just the flu. The local view of the virus helps counter misinformation from Brazilian politics.”

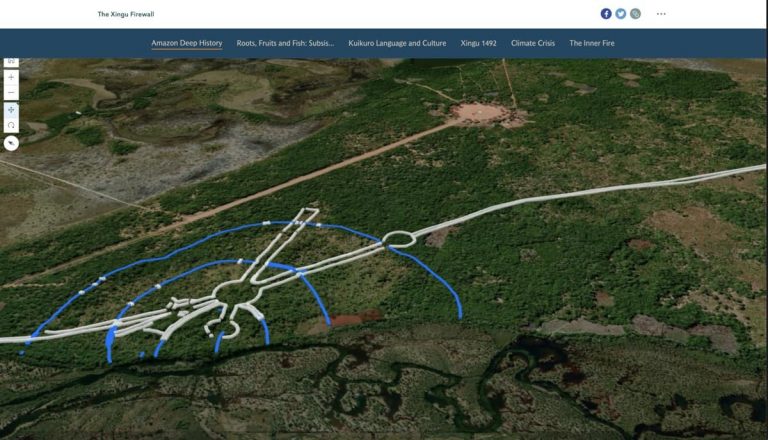

In 1993, Heckenberger went to live with the Kuikuro people who showed him earthen structures created by their pre-Columbian ancestors. Using a GPS receiver, he started piecing together a large network of sites, and placed them on a map. The effort revealed two complex urban clusters connected by roads, bridges, and canals for canoes. Mapping revealed large circular villages protected by defensive earthworks and ponds for fish farming—a practice that continues today. The archaeological settlement patterns are different than urban development elsewhere, but 1,000 years later a similar layout is seen in modern villages, including large central plazas for gatherings and ceremonies.

A long view of culture and history that combines archaeological evidence with modern ethnography helps document dramatic declines in indigenous population over time. “There were 50,000 or 100,000 people there at one point, but only 500 of them left in 1950,” Heckenberger said. “This is one of the most remarkable tribes in either North or South America for the persistence of native traditions since 1492.”

Today, there are 3,000 indigenous people living in 32 separate villages on or near the Xingu River, small gains over historic lows now threatened by the pandemic.

The research involves capturing local knowledge, combining that with satellite imagery, and building maps to uncover and preserve the past. His work has been energized by the idea that understanding ancestral practices can help the tribe live more sustainably today. Of particular interest are resource management strategies and landscape engineering practices that might mitigate the rising threats from droughts and wildfires brought on by climate change.

“We’re trying to strengthen the tribe’s capacity to address large-scale questions of deforestation, fire, and now pandemics,” Heckenberger said.

Village chief, Afukaka Kuikuro, supports the technology project, embracing the idea of using the tools to record cultural details and help safeguard the tribe. He now takes regular conference calls with a group of collaborators who work to advise, assist, and advocate for the tribe’s safety. Right now, the priority is protection from coronavirus.

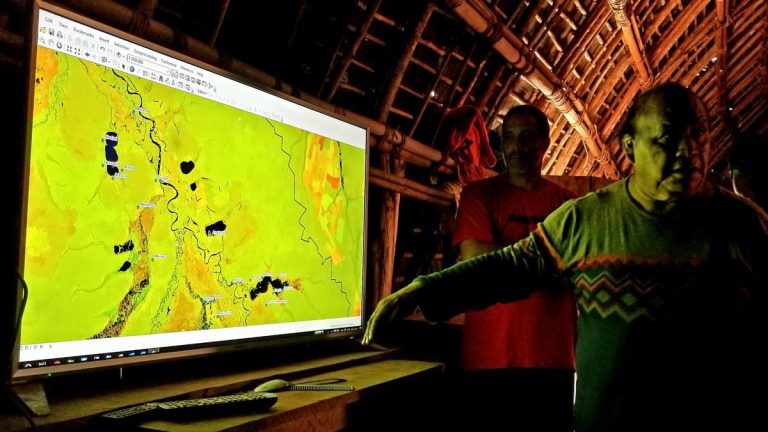

“In a typical meeting there’s three languages happening at one time— English, Portuguese, and Kuikuro,” Heckenberger said. “Meanwhile, we have a map. The chief is pointing, and others are talking, and there’s an inherent understanding of geography. He can communicate with scientists and his own people really effectively with this map.”

Because maps cut across language barriers and convey a common understanding, GIS has become a tool to take action and enhance collaboration.

“The most costly and precious part of this work is the relations we have with the Kuikuro,” Heckenberger said. “COVID has been kind of a remarkable and privileged moment. People are willing to suspend any differences and work together.”

The work started with a census, going door to door to record names, ages, and other details about each villager. The tribe knew their own people but placing them all on a map meant they could begin understanding interactions.

“Now, the four villagers we trained go every day to find out who has come into the village,” Heckenberger said. “They fill out a multi-page form that lets the doctors and other healthcare workers know how many have left, who is in isolation, and who needs to be.”

Three villagers who have been the designated data gatherers have taken to the technology, with only minimal training.

“They’re not really accustomed to book learning, and something like a formula is completely foreign to them,” Heckenberger said. “Tactile and geospatial information is something that comes natural to them and they really embrace it. The Kuikuro have an innate cartographic sensibility. You teach them once and they pick it up.”

In addition to determining who has traveled in or out of the village, the field tools capture motives for the movement.

“They were leaving the villages to go to the cities for supplies,” said Bruno Moraes, the operational director of the Amazon Hope Collective and the archaeologist who trained the villagers on the use of the tools. “They used the platform to ask people what they needed and set up a delivery system.”

The handheld tools are helping keep updated maps of the entire village to minimize the spread of disease.

Though the mapping platform was developed and implemented without COVID-19 in mind, the tribe is embracing the technology’s flexibility to address its most immediate needs.

“We switched off the other things we were mapping and turned to the sociological problem of avoiding the spread of COVID,” Moraes said. “In the process, we may save lives, and that’s the nicest thing we can do with all the work that we’ve been doing over the years.”

Most of the other indigenous groups in the region have suffered many cases and deaths from COVID-19. The Kuikuro have escaped the worst outcomes thanks in part to good leadership, outside support from longtime collaborators and partners, and a modernized approach to visualize, analyze, and attack the crisis.

The idea of losing elders hits at the root of a tribe’s identity. These keepers of the culture pass down stories, traditions, and language. In response to COVID-19, tribal leaders have canceled Kuarup, the annual festival that brings together all the indigenous tribes in the Xingu national reserve between July and September to mark the deaths of those who passed the prior year.

Takuma Kuikuro, coordinator of the Kuikuro Film Collective, told a reporter, “This is a very sacred period for us. It was a very hard and traumatic decision to make because we don’t know when we will be able to mark the date. And we fear that a possible erasure of our history and our memory is underway.”

The global crisis is motivating Heckenberger and others who work to deliver technology to Amazon tribes to help them not only reveal their history but preserve their way of life. The COVID-19 solution leads this effort with outreach to expand the solution to more tribes.

“We hope to extend the Kuikuro model to help these other groups,” Heckenberger said. “We’re hoping to get to the point where we can deal with the entire regional system, the whole indigenous area, which is about the size of Vermont.”

The project has been focused on creating capacities with villagers who become co-participants and co-administrators. With COVID persisting, the research teams says larger groups in the area are getting excited about using the technology. Now, the team hopes to collect basin scale data—a large regional dataset—to protect some of the last large intact tracts of Amazon rainforest, which are managed and protected by indigenous communities.

“We’ve been very careful to orient the people and motivate them to learn the tools,” Heckenberger said. “They participate in the collection and dissemination of data so they can train and convince other indigenous groups.”

Learn more about how GIS is used to respond to ecological crises. The Kuikuro community has reached out to raise funds to help overcome challenges of the COVID-19 crisis.

All images of the tribe are courtesy of the Associação Indígene Kuikuro Do Alto Xingu (AIKAX).