November 21, 2022

In the late 1980s, Jane Goodall was flying over Tanzania’s Gombe National Park in a small plane and gazed out the window at the place she’d called home for 30 years. She was shocked by how vulnerable it was.

As she recounts in Local Voices, Local Choices, a new book by the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) and Esri, the place where she famously knocked down a series of towering, long-held assumptions about primates and humans looked like an island of trees, completely encircled by human settlements, agricultural footprints, and deforested hillsides. The land around Gombe had become overfarmed and infertile, as local communities had cut down the trees for charcoal to sell or to feed the stoves that cooked food for their families. Without healthy habitat corridors extending outward, Gombe’s island of forest would give its chimps no chance to be reunited with other populations nearby.

Stress on humans trying to survive was putting more stress on nature too. How could humans protect their chimp neighbors, Goodall realized, “while the people living around the borders were struggling to survive, envious of the lush, forested area from which they were excluded? That’s when it hit me that unless we could help the people find ways of making a living without destroying their environment, we could not hope to protect chimpanzees, their forests, or anything else.” Any efforts to conserve chimpanzees and their habitats would need to empower nearby communities to develop more sustainably, not just as collaborators, but as leaders and stewards of their lands.

In 1994, with help from the European Union, JGI began an outreach program in the villages around Lake Tanganyika. Called the Lake Tanganyika Catchment Reforestation and Education program, or Tacare (pronounced tac-ar-eh), it focused on the idea that local people are most connected to their environment.

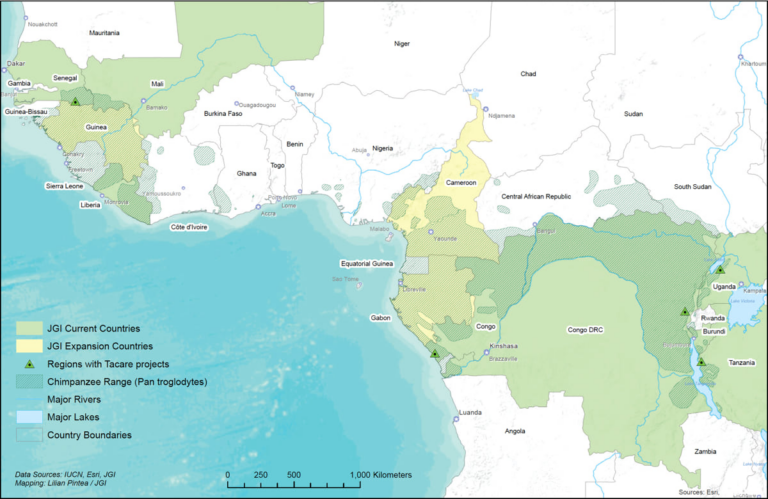

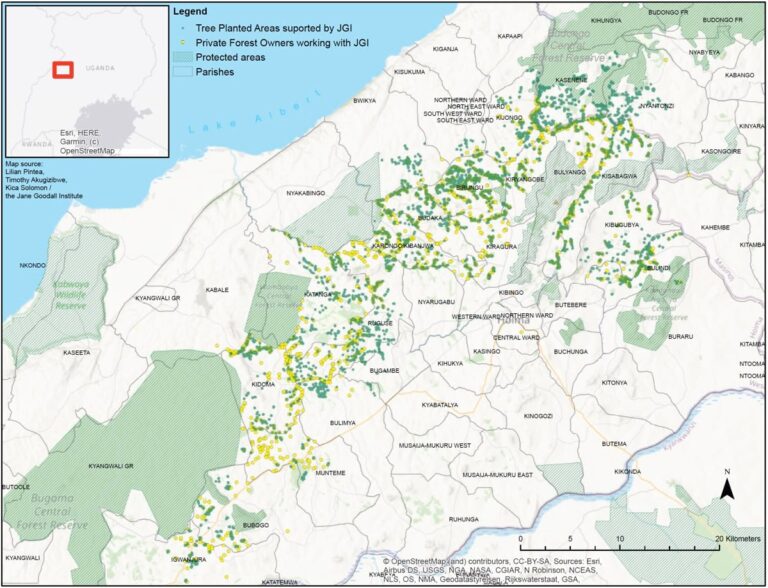

Nearly 30 years later, the Tacare model has been part of conservation and sustainable development in over 100 communities across Tanzania and inspired similar programs in Burundi, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Senegal, and elsewhere in the world. Tacare, which now simply stands for “take care,” follows five main principles—engage, listen, understand, act, and empower—and uses maps created with geographic information system (GIS) technology to help facilitate community participation and manage and track change.

Of course, the risks of biodiversity loss—and the causes—extend far beyond the villages that abut wildlife habitats. The reminders of these risks have been everywhere, as greenhouse gas pollution from one country’s coal industry wreaks havoc on ecosystems across the globe, and as viruses like COVID-19 remind us that human activity around natural habitats can introduce new zoonotic diseases and even society-halting pandemics.

Still, it’s the people who live closest to wildlife who are most imperiled by broken ecologies.

For the indefatigable Goodall and the book’s inspiring cast of characters, this proximity to the problem is also a path to a new approach, in which the future of biodiversity and resiliency is in the hands of locals, aided by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and governments. These communities rely on healthy ecosystems for access to basic services such as clean water, and they are best positioned to protect it. This is the basis of Tacare.

Think of the world’s protected parks and reserves, conjured up from National Geographic and David Attenborough documentaries, and you might imagine a giant, infinite expanse where wildlife can roam free. But grab a map and you’ll see that these places don’t exist in a vacuum: increasingly they’re right next to where people live. Conflict often ensues.

As Goodall notes, the world’s most ecologically significant spaces exist in between reserves—places like the margins of protected parks, where the human-wildlife interface represents a perpetual tug-of-war over land and resource use. Protected spaces contain only 20 percent of the world’s biodiversity; the rest is found in areas colonized and often overused by people just trying to survive.

As part of the initial Tacare program in 1994, Goodall and her colleagues put together a team to go into the communities surrounding Gombe, listen to their needs, and develop a program to help. The team found a litany of threats to nearby chimps and overall sustainability, especially the clear cutting of trees for charcoal production, which led to erosion and worsened the risk of landslides and wildfires. Those kinds of disasters destroy soil and vegetation, hurting wildlife, halting seedling reemergence, and ultimately eroding old traditions and communities’ very ways of life.

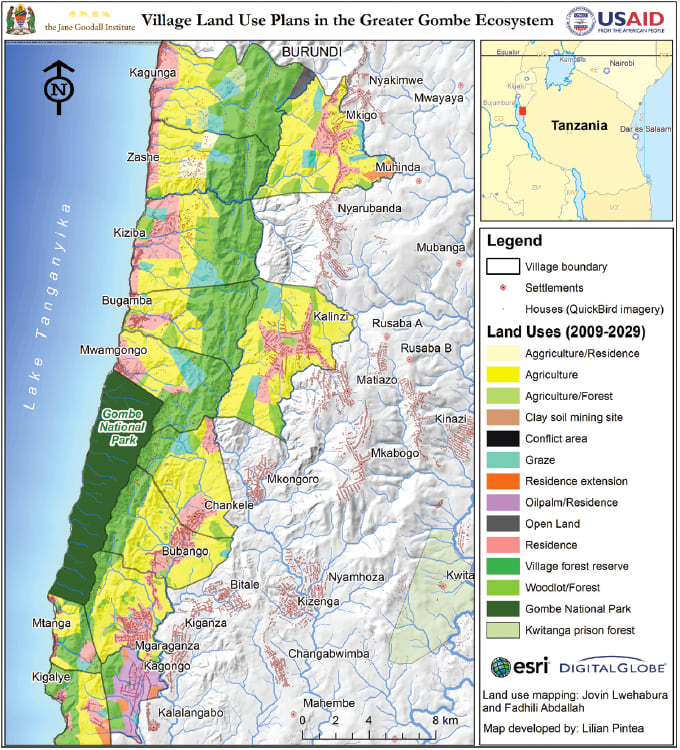

One of the first critical issues JGI faced was how to designate land title and ownership. In the upper hillsides where the chimps were still traversing, there had never been any demarcation between the villages. A process of physical demarcation, conducted with a committee from the lakeshore village and a committee from the highland village, would determine the boundary, in one of JGI’s earliest spatial or mapping efforts. But geospatial technology wouldn’t enter the picture until 2000, when a PhD student named Lilian Pintea showed up.

Pintea’s love for wildlife had led him from a small town in Moldova to the University of Minnesota, where he studied conservation biology at the Jane Goodall Institute’s Center for Primate Studies, applying GIS and remote sensing to chimpanzee research in Gombe. One of his earliest projects was straightforward: Pintea joined a group of government officials, engineers, and community members at Gombe to, at last, help georeference and mark the boundaries of the park.

But this wouldn’t be easy, and drawing up land plans around that boundary would be even less so. Over the years, multiple evictions from protected land and a lack of boundary demarcations had sowed mistrust in the surrounding communities, which made some resistant to preserving trees or doing anything that would add to the forest; some actively hunted chimps outside the park, for fear the chimps’ territory would be appropriated by the government. At first, many locals feared, understandably, that any new planning process, no matter how participatory, would be used to expand the protected forest area, absorbing more of the community’s land.

Pintea is now JGI’s vice president of conservation science, leading its geospatial efforts around the globe; with Adam Bean, JGI’s manager of conservation science, he edited Local Voices, Local Choices. But as he and his colleagues and collaborators emphasize in the book, GIS is more than just a tool for conservation science or even sustainable planning. It’s also a powerful communication tool, conveying ideas about the past, present, and future in ways that a presentation or a slideshow often couldn’t.

Rather than tell local communities what’s wrong with their environment and offering ways of fixing it, Pintea could now show them. By illustrating the interconnected needs of people, animals, and the environment, a map can help illustrate, for instance, how deforestation has led to landslides. But a meeting might start by simply laying down a map and letting the community talk.

“‘This is a place where we do our rituals,’ someone might eventually say. “‘This is where my farm is,’ and then they discuss a little bit and say, ‘This is where we fetch our water,’ ‘This is our burial site,’ and so on.” Pintea said, adding that points of interest like that “breathe life and history into a piece of paper. But when incorporating science and technology, you don’t tell them, ‘This is what you do,’ ‘This is how you use it,’ etc.”

At the same time, Pintea and his colleagues were learning how to incorporate the technology—and a wealth of new geospatial knowledge—into the planning process.

An important lesson arrived one day in 2001. Not long after his arrival in Gombe, when Pintea and Goodall and others learned that a flash flood had ripped through the nearby village of Mtanga, destroying homes and killing people. After a solemn meeting with village leaders, Pintea and his colleagues left worried about the future: unsustainable farming was still eroding the local landscape and destroying trees, which, combined with the growing effects of climate change, only made such disasters deadlier. More extreme weather was coming.

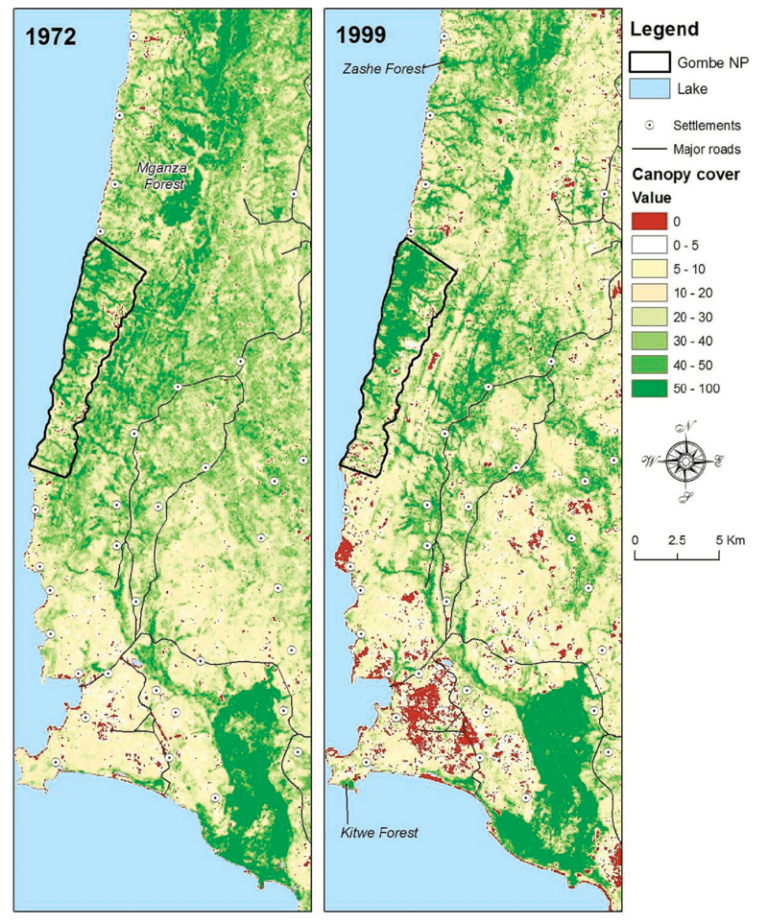

Pintea drew up new maps. First, he mapped the forest cover change inside and outside Gombe around the time Goodall first arrived in 1960, using satellite images from the Landsat program. The images revealed an “entire landscape . . . covered by a mosaic of forests, woodlands, and grasslands connected to Gombe,” he recalls.

Then Pintea downloaded up-to-date, one-meter satellite images over Gombe from IKONOS, the first commercial satellite to gather such high-resolution imagery from space. As he and the villagers studied the amazingly detailed images, featuring every tree, house, and footpath, recalls Pintea, “we were shocked to confirm that most of those forests and woodlands outside the park were converted to subsistence farms, settlements, or cash crops such as oil palm.”

To begin planning for the future with locals, maps became crucial, even simply as a conversation starter. The new satellite imagery helped locals identify features significant to them, which made it easier for them to appreciate the devastation that had already happened and see what could come next for their village.

“The image of a lush and green Gombe surrounded by bare, deforested land was important, because it allowed us to then sit down with the local people and have a dialogue about what was happening,” Pintea recounts. “This gave them a spatial context, and it gave them a collective, transparent, and objective look at how their land uses had been changing their landscape.”

The new satellite imagery was cool, but as Pintea worked with the Tacare teams, he was also inspired by the “dirt maps,” drawn with sticks and rocks, that were common during planning meetings. Why not, he thought, incorporate more direct community participation into the GIS data? As JGI’s teams worked more closely with local communities in a handful of villages, large printouts of digital maps, handy for group markup sessions, became frameworks for an eye-popping new understanding of the landscape.

With smartphones provided by JGI and using Esri’s ArcGIS Survey123 mobile app, communities monitor the forest themselves, bringing them closer into the GIS process and the day-to-day planning for conservation. On these maps, local and Indigenous knowledge combine with data, science, and technologies to allow users to see and track everything from trees to houses to farms and water sources and even spiritual and sacred sites.

This transparent, common understanding of the area provides a way to discuss aspirations and a platform to start to deliberate about the future. “If you impose plans, you will not get anywhere,” says George Strunden, an agricultural scientist from Germany who started the first Tacare programs at JGI and gets his own chapter in the book. “The people have to feel that this is something they came up with and they decided to do.”

It’s also important not to rely too heavily on the satellite data. “The remote sensing imagery gives you great information on where the vegetation was changing over time, but it doesn’t always give you an insight into why it’s changing, and it doesn’t give you any strategy on how you can influence people to alter the way they do things there,” Strunden says. “That still lies in the relationships you have and the discussions you have with people and how you engage with them to effect change.”

Once the process has begun, land planning efforts ultimately won’t succeed if the communities themselves don’t see a value in improved land management and if the program doesn’t include any ways for them to generate income. That means showing people the value of new agriculture production, like honey, mushrooms, and medicinal plants, and helping communities secure protected access to firewood. It also means incorporating locals, some of them former poachers, into the conservation and mapping process itself.

Mobile geospatial technologies can be novel but empowering; training communities to do their own mapping can help enhance community cooperation. It’s a more direct way of showing people that their stewardship of nature can pay off, by literally paying them for it.

These participatory efforts pay off for the ecosystem in the long term too. When setbacks happen or things change—perhaps new village leadership comes in and ends a planning process—the close involvement of community members and the long-standing relationships developed through Tacare mean that locals are more likely to keep honoring those land-use plans.

“Because you’ve taken the time, the local communities really understand why some of these things are happening,” says Alice Macharia, vice president of Africa Programs for JGI, “and they continue to support those processes.”

This local and iterative approach isn’t always easy, as a diverse mix of scientists, conservationists, village leaders, and community forest watchers attest in Local Voices, Local Choices, a kind of biography of Tacare. But it’s that eclectic mix of people—often communicating and connecting ideas and plans through maps—that has also helped make Tacare a proven approach to conservation.

For Goodall, it’s more than that. Out of the horror of that view over Gombe and over years of other ecological disasters, Tacare, she writes, has evolved into “the very embodiment of hope for the future of our planet.”

Read the second installment on Wednesday, with details on how disaster spurred conservation. Explore more about how GIS helps achieve sustainable conservation with the power of geography.