July 14, 2020

In February 2019, geospatial analyst Lindsay Chan found herself belly crawling through thick coastal brush on New Zealand’s Auckland Island in pursuit of yellow-eyed penguin chicks. As the San Francisco Bay Area native wriggled her way along the small trail left by the endangered fowl, she was overwhelmed by the unique aroma left by the penguins, sea lions, and possibly feral cats.

Yes, cats. Chan and her team at the New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC) estimate that more than 2,500-5,500 feral cats—along with countless mice and a healthy herd of feral pigs—live on Auckland Island, which is located 465 kilometers south of New Zealand’s South Island, within the subantarctic area.

As romantic as a colony of marooned farm animals might sound, they’ve been destroying the native flora and fauna on this windswept island for more than two centuries. Of the 38 native species that breed in the archipelago (nine of which are endemic), only 13 still breed on the main island. Part of a larger Predator Free 2050 initiative, the Maukahuka project is an ambitious proposal to eradicate all non-native pests from Auckland Island.

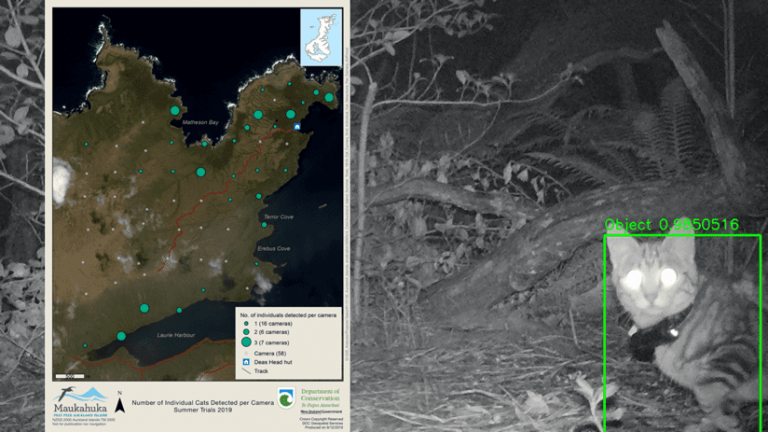

Chan and her team use a geographic information system (GIS) and smart maps to identify cat populations, track their movements, map their locations in relation to endemic bird populations, and develop a removal strategy.

The team sees GIS as integral to the project. Would Maukahuka be possible without it? “GIS is essential, from working out what we think the population density of pests are before the project starts to monitoring where the helicopters apply bait during the eradication, it supports all parts of the project,” Chan said.

Over the last two years, Chan and her team on the Maukahuka project have been conducting feasibility studies to determine if the eradication of pigs, cats, and mice is actually possible. There is zero margin for error. “Because it’s an eradication project, we can’t miss a cat,” explained Chan. “It would be different if it were predator control and we were just trying to keep the population low. But if you have one missed cat, years of planning and project work is put in jeopardy.”

In its fight against feral cats, the team faces an incredible number of challenges, most notably the massive size and glaciated topography of Auckland Island, which is approximately 43 kilometers at its longest point and 27 kilometers wide and has a coastal perimeter of 374 kilometers. It’s consistently wet, cold, and windy, with sheer cliffs and mountains up to 650 meters high. The eradication of mice and pigs has never been achieved on an island this large, and removal of cats has only been attempted on one larger island, in Western Australia.

Given the scope and audacity of the project, GIS has proved to be an essential tool for the team to collect field and historical data and model different strategies for eradication. GIS software is able to layer, process, and analyze massive amounts of data through the lens of location and articulate the results on a map or 3D visualization.

So how did pigs, cats, and mice find themselves forsaken in this cold, blustery corner of the world? It started in 1806, when British mariner Abraham Bristow became the first European to encounter the islands. Recognizing the likelihood of the archipelago to cause future shipwrecks, he returned one year later with a drove of young pigs in the hopes that they could sustain stranded whaling and sealing sailors.

Over time, additional animals were brought to the islands, either intentionally or by accident, including sheep, goats, mice, rabbits, cats, and cattle, the sealers, whalers and settlers that came and went through the 19thcentury. Marooned sailors from at least nine shipwrecks over the next century (for which a poorly drawn 1828 navigation chart of the South Pacific Ocean is partially to blame) suddenly found themselves on islands with a thriving food source. The most famous of these historic events was the 1866 wreck of a gold-carrying American ship called General Grant.

The imported pigs have devastated critical native plants, including megaherbs, which evolved with oversized leaves and flowers to survive Auckland Island’s extreme climate. The invasive animals also threaten seabird survival. Cats hunt birds whilst mice have the potential to prey on ground nesting birds and their eggs on Marion and Gough Island. Pigs have altered the abundance and composition of invertebrate fauna and they compete for food with the island’s bird populations. The predators have restricted native bird species like white-capped mollymawks into breeding in only the steepest refuges.

DOC has undertaken several campaigns since the 1980s to rid the subantarctic islands of pests, but the pigs, cats, and mice remain on Auckland Island. With the exception of a few human visitors, the animals have been largely unthreatened by any predators and have flourished, to the detriment of the indigenous residents.

Chan was asked to help conduct fieldwork and test various cat detection tools on Auckland Island as a member of the “cat team.” Along with 11 colleagues, she made the treacherous two-day voyage from New Zealand’s South Island to Auckland Island in rough seas. “At night, I lay on my bunk, looking at the skylight, with my arm braced against the dresser so I didn’t get thrown out of my bed, watching the waves crash over us,” she recounted. As the boat glided into the harbor, it was greeted by a raft of swimming penguins – a warm welcome after the nauseating journey.

During their six-week stay on the island, Chan and the team slept in a small communal hut and spent most of their time out in the field, testing tools and answering the questions, “Do we only need one tool? Do we need multiple tools that will complement each other? Are there some tools that actually aren’t useful?”

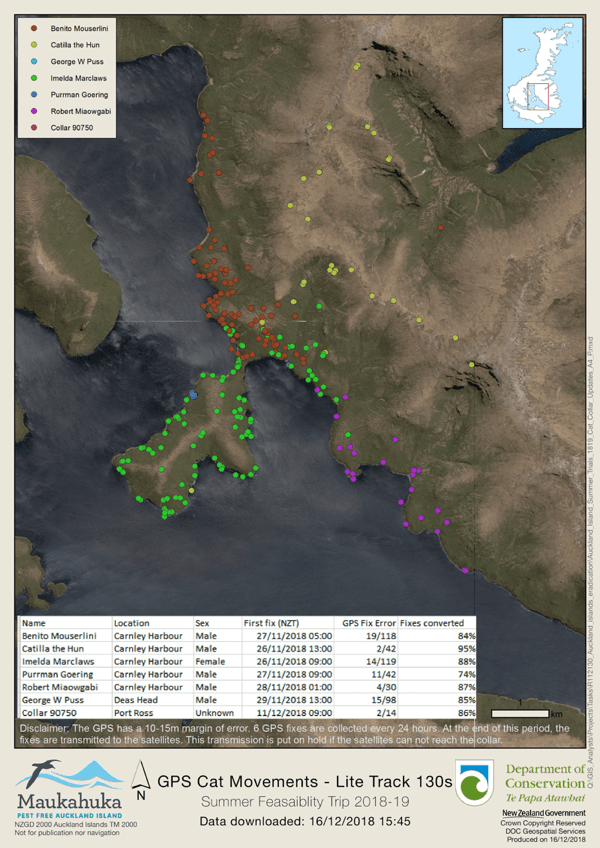

Chan explained some of the methods they used to assess the situation. “We had traps to catch cats so we could affix GPS collars that would track their movements. We laid [out] a camera grid to detect all the known cats in the area. And then we were also collecting scat and tracking cats with conservation dogs.”

The team members then had to analyze thousands of points of data collected from the various cat detection sources. Chan used GIS to help connect the dots and expand their view. “We were able to answer questions like, ‘Was there a cat there, but we missed it on camera?’ In one case, we determined that a cat had been in a certain place because a dog caught some scent there, a GPS from a cat collar placed it nearby at 11:00 a.m., and then we found a scat that was fresh—but we didn’t happen to pick it up on the camera.”

Chan also used maps to help track the movements of cats with GPS collars. By translating location coordinates from a spreadsheet into a smart map, the team could see where higher concentrations of cats were located as well as track and analyze the movements of individual felines.

In one case, a cat the team had been monitoring in one area suddenly made a 20+ kilometer journey to the other side of the island near sea cliffs. The bird expert on the team explained that it was time for petrel fledglings to hatch on the sea cliffs, and the cat could possibly be hunting. Chan explained the value of GIS in that situation. “Maps and GIS can communicate the story so much better. We had the GPS fixes and could see that certain numbers were quite different from other numbers, but without putting it into a spatial picture, we couldn’t really pick up on the fact that this cat is on one side of the island, and it’s moved all the way to the other side where the cliffs are, within a span of 24 hours.”

Following the success of the feasibility studies, the Maukahuka project was put on hold due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and is waiting for when the economic climate allows.

Chan didn’t set out to become a geospatial analyst bushbashing around the subantarctic islands in search of feral cats. In fact, her only exposure to GIS prior to moving to New Zealand five years ago was during a geography course at Colorado College, where she was a sociology major and played Division III lacrosse.

Chan arrived in New Zealand’s Christchurch in 2015 during a time when the city was still recovering from a devastating 6.2-magnitude earthquake in 2011. One of her first jobs was with an engineering firm, helping to rebuild the underground water system infrastructure. She realized right away that the job she had been given could be done much faster with GIS. “We were part of the bigger rebuild project,” she said, “so I managed to find my way to a different office that had GIS capabilities, and I just started talking to [the staff].”

Chan kept in contact with the GIS team and eventually got her first GIS-related job doing basic data entry and analysis. From that point, she was hooked on geospatial analytics and did everything she could to learn more and expand her network.

Since Chan was self-taught in GIS, she also wanted to assign herself a sort of GIS dissertation project. “Because I was getting into GIS and doing self-study, I began to explore the different apps and software I could be using, she said. “As someone without a degree or background in it, I wanted to get some experience and create something for myself.”

Chan became inspired while on a public art bike tour. “We were led around Christchurch by a volunteer; and by the end, I was amazed by all the different graffiti and murals,” she said. “I wanted to know all about them and who made them.”

Chan started documenting all the different public art and adding it to a smart map, along with information she uncovered about each piece. She called the project Watch This Space. As it grew, created a charitable trust, built up a group around her and launched a website with interactive public art walking maps and a way for people to submit pictures of works that were not already on the map.

“I wanted to capture the stories, the inspiration behind each piece, and the artists and share that story,” Chan said. “It’s something visitors to Christchurch can use now, but it’s also something that we can look back on like 10, 15 years from now or even later when the city is fully rebuilt and these pieces no longer exist.”

This early foundation in GIS set Chan up for the career she enjoys today—one where she is tracking cats, pigs, and mice for the sake of conservation. Though her job description of geospatial analyst probably doesn’t evoke images of research on a far-flung island, Chan says fieldwork is one of her favorite parts of the job. “I enjoy going out into the field to learn about and understand the needs of the team on the ground so I can help find solutions back in the office that can make their work easier for them. Being able to go out into the field and knowing that I’m doing a job that does good and can benefit other people is really rewarding.”

Learn more about how GIS is being applied to respond to ecological crises and to restore biodiversity faster.