August 24, 2021

In April 2020, as the magnitude of the coronavirus pandemic and its impact were becoming readily apparent, Commander Ryan Clapp, a staff engineer with the Indian Health Service (IHS), flew to Albuquerque. Upon arrival he bought eight pay-as-you-go cell phones from a retail store and loaded data collection apps on them. Within 48 hours he had a team of Navajo Area IHS technicians spread out to map water access points on the Navajo Nation using the mobile devices.

While he was in the air, IHS headquarters staff were developing a comprehensive field survey, talking to the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, and doing all the background work. “We were building things as we were going, and it was moving very fast,” said Captain Ramsey Hawasly, assistant director, Division of Sanitation Facilities Construction at IHS and lead GIS program coordinator.

This rapid response was requested by the Navajo Nation president due to the COVID-19 public health emergency. At the time the Navajo tribe was experiencing the highest incidence of COVID-19 cases in the United States, and the long-standing lack of in-home water access was assumed to be a driver of these infections.

The heightened need for handwashing during the pandemic posed a challenge for the many homes without water. For many years, the rugged topography and remoteness of the Navajo Nation made piping water to homes challenging. Since 2003, IHS and a network of partners have reduced the number of Navajo homes without water access from 30 percent to 20 percent. New funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided the Navajo Area IHS with $5.2 million, targeted specifically to increasing water access on the Navajo Nation.

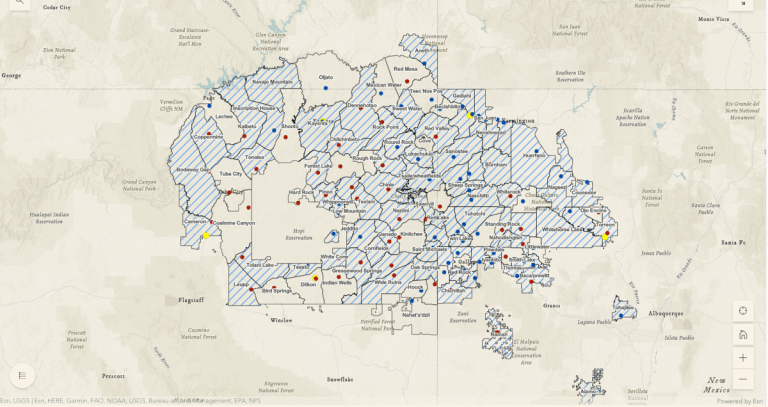

The IHS team used a geographic information system (GIS) to map and share construction progress on new water access locations. Many are at or near chapter houses, which serve as county-level governments.

“We were able to collect data in all 110 chapters with just six surveyors, covering an area the size of West Virginia in just two weeks,” said Captain David Harvey, deputy director, Division of Sanitation Facilities Construction at IHS.

Through the GIS data collection efforts, the CARES Act funds supported the installation of 59 new transitional water point (TWP) connections to existing public water systems; supplied 37,000 water storage containers; distributed 3.5 million water disinfection tablets (where needed); and subsidized the water for people living in homes with no piped water through February 2023.

The data that Commander Clapp and the team collected was critical in identifying locations for needed facilities. It set in motion additional mobile work to design each access point, calculate construction costs, and place orders for the right amount of pipe needed to make new connections.

The fast-paced construction lasted from mid-July through September 2020. It was guided and communicated through shared maps and plans at each step of the way. An online interactive map marked progress for each chapter. In addition to the online map, a regularly updated map appeared in tribal newspapers because the paper is the primary source of information for many homes.

“We were changing colors on the map, based on whether or not there was an identified transitional water point for each chapter,” said Captain Shari Windt, engineering consultant, Environmental Health Support Center at IHS. The map changed when water points were slated for construction, design was being done, the construction was complete, and the water point was open. A final color was used when a chapter had all the interventions available.

The map guided the workers and the people they were serving to the new TWPs. Using GIS analysis, IHS calculated that the travel distance dropped from 52 to 17 miles, saving people an average of 38 minutes behind the wheel for each trip.

Just as the water access work was wrapping up, the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources (DWR) reached out to IHS under a separate request for help on bridging the gap for remote homes without access to a piped water connection.

DWR requested that IHS provide detailed design project drawings for a water cistern and on-site wastewater disposal facilities. Again, IHS deployed 15 Commissioned Corps engineers and environmental health officers of the US Public Health Service to undertake data collection.

“The cistern project is really beneficial because you can have bathrooms with showers and toilets, and sinks in kitchens,” Commander Clapp said. “The homeowners still have to haul water, but it’s a bridge to more sustainable services such as a connection to a piped water system.”

The data in the STARS system combined with analysis in GIS allowed IHS to identify 900 top candidates and provide a map of those homes.

Commander Clapp led three teams made up of five people that each spent a month in the field on assessments. For each home visited, the team gathered design data from the site to determine where the water storage tank and sewer facilities should go. Team members also assessed any potential problems, such as the location of large rocks or obstacles that might hinder construction or site access.

“It was a collaborative effort, and it was done in a quick and efficient manner,” Captain Hawasly said. “The Navajo Engineering and Construction Authority could access the data collected to quickly create plans and drawings for approximately 70 homes.”

This pandemic work spurred the creation of the Water Access Coordination Group, which includes four Navajo government entities, six federal government agencies, three universities, and two nonprofits. Bringing water to homes is something that everyone working on these projects feels passionate about.

“It shouldn’t have taken this disaster to get us here, but now there’s a whole new recognition of what tribal resilience means and how the federal government can work together,” Captain Harvey said.

This project has received the Cumming Plaque from the Society of American Military Engineers, and Captain David Harvey received several awards, including the Public Health Service Officer of the Year from the US Public Health Service and the Agnese Nelms Haury 2020 Tribal Resilience Leadership Award, for spearheading the collaborative effort.