April 8, 2020

When the COVID-19 pandemic reached Pennsylvania, it hit Montgomery County first. By March 12, these northern Philadelphia suburbs accounted for 13 of the commonwealth’s 22 confirmed cases.

In the weeks leading up to the local coronavirus outbreak, businesses throughout the Philadelphia metro area had braced for its impact. More than 20 local organizations—comprising experts in economic development, small business management, tourism, destination marketing, international business, the technology sector, and venture capital—were already trading notes on strategies to support the business community.

Economic development officials in several counties and municipalities had also begun to conduct informal surveys of local business owners to gauge how much of a hit they had already taken, what they feared would happen to their businesses in the future, and what kind of assistance they would need.

Several officials were already floating the idea of collaborating on these survey efforts. Montgomery County took the lead, organizing a centralized survey of businesses that extended to the neighboring counties of Bucks, Chester, and Delaware, along with the city and county of Philadelphia. Taken together, it should add up to a detailed economic picture of a large swath of the Delaware Valley.

Pennsylvania ranks among the world’s 30 largest economies, with a gross domestic product (GDP) higher than Switzerland’s. Around 40 percent of that economic output comes from the five counties that are part of the survey.

“Economies do not stop at community or county borders,” said David Zellers, Montgomery County’s director of commerce. “We need to work together as a regional team to flip the switch when the economy is ready to start again.”

The first round of surveys went out on Friday, March 13. That first weekend, 440 were returned. By the end of the month, the effort had yielded useful data from more than 1,000 businesses and companies.

The surveys are a way for officials like Zellers to chart how COVID-19 is affecting—and will continue to affect—businesses across various sizes and sectors.

Although the region itself is economically and demographically interdependent, there may be ways in which certain types of businesses feel the crunch in different ways. Location intelligence will be a vital aspect of the analysis, helping answer questions that will impact strategies.

In a time of social distancing, will the density of Philadelphia serve as a help or a hindrance? In the suburbs and exurbs, will a declining population in office parks and campuses have a ripple effect for nearby support businesses? As government aid flows into the region, will certain areas see more of it than others?

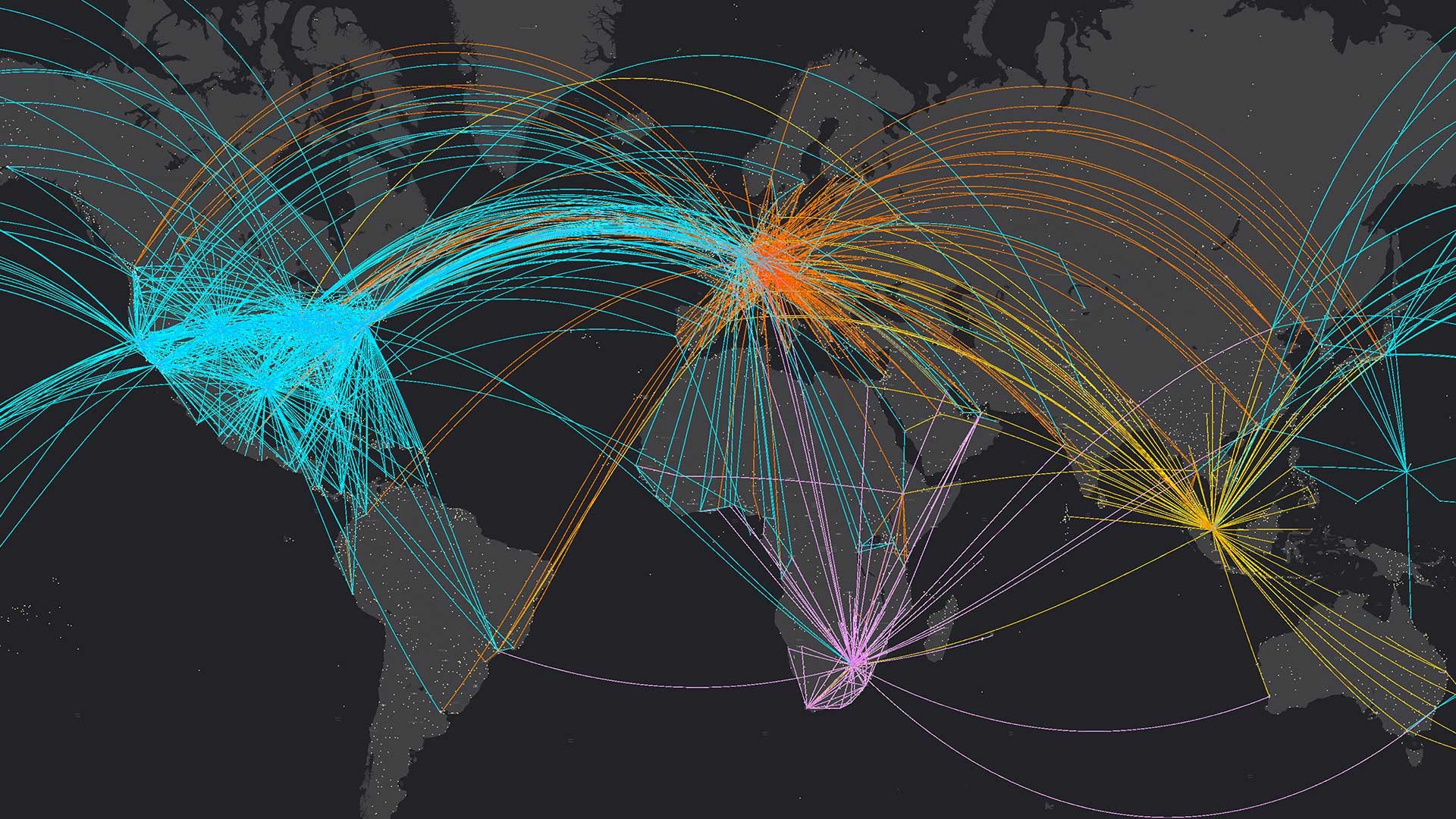

To help answer these questions—and, just as important, to visualize answers—all relevant data will live in a geographic information system (GIS). Interactive GIS maps will provide an intuitive way to see, at a glance, how businesses in different areas are handling the difficult task of rebuilding. GIS dashboards will provide a means for bringing in other types of datasets, such as unemployment statistics and revenue from tourism.

“I think as we gather more results over the next week or so, and we look beyond the immediate public health situation, geospatial analysis is going to be very important,” Zellers said. “We will start understanding where the impacts have been and the magnitude of those impacts across sectors and across communities.”

There is a poignant historical aspect to this effort to understand the effect of COVID-19 on the Philadelphia area. During the massive Spanish flu epidemic in 1918 that killed 50 million people worldwide, Philadelphia was one of the hardest hit American cities. Nearly one out of four residents of the city contracted the disease and 16,000 died. During one five-week period, the death toll averaged 385 per day.

The economic fallout survey will also serve as an important building block for the region’s future. The area is a central hub for such industries as finance, advanced manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, life sciences, and logistics.

Zellers hopes the survey can serve as a longitudinal study that documents the rebuilding of the area’s economy over a long period of time. In the coming months—and even years—the study will help officials and researchers learn about more than just the Delaware Valley’s economy. It will also help them understand the rebuilding of all the world’s advanced economies.

Zellers sees GIS as key to this understanding for its ability to give numbers and statistics a real-world context. “The analytical piece of this is so important—and being able to visualize all of this makes a huge difference,” he said.

Officials believe the project will serve as a model for the collaborative approach essential for rebuilding local economies.

“Recovery is not a siloed process,” Zellers explained. “We want our communities to know, and we want our elected leaders to know, that we’re working together on this. We’re united, not just in collecting data, but also in the strategies we want to promote to help every person here move past what’s happening right now, and have a stronger region in the future.”

Learn more about the role of GIS for planning and economic development.