Before people would say Argentina has little control of the sea. Now, word is getting out about our tracking system and it is harder for offenders to try to fool us.

September 5, 2018

Real-time System Tracks World Oceans for Anti-Poaching Awareness and Evidence

Shortly after dawn in late February 2018, a Chinese fishing boat raced to rejoin its fleet off the coast of Argentina. Prefectura Naval, the Argentine coast guard, emerged through the fog in hot pursuit to intercept the boat, which had been fishing illegally in its waters. Despite shots fired, the foreign vessel evaded Prefectura Naval by surrounding itself with other Chinese fishing boats and re-entering international waters.

Prefectura Naval patrols its coast nonstop during the annual spawning run of the Argentine shortfin squid—February through April. Conflicts with poachers are common. In a similar incident in 2016, Prefectura Naval sank a Chinese fishing boat that tried to ram its patrol ship in a desperate attempt to escape.

With 90 percent of the world’s fisheries fully exploited or facing collapse, according to the United Nations, fishing vessels from around the world converge on places like the coast of Argentina where stocks are still abundant. As many as 2.2 billion pounds of this squid (Illex argentinus) have been caught in one season, making Argentina’s coastal waters the second largest fishery in the world by weight. Most of the catch ends up as fried calamari, a popular item on restaurant menus worldwide.

Most squid jiggers operate in unrestricted areas just outside Argentina’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), which extends 200 nautical miles from the country’s coastline. But, many ship captains dare to dip inside the EEZ boundary thinking they can quickly fill their holds without getting caught.

Prefectura Naval deploys patrol boats, helicopters, and airplane spotters to protect its economic interests and guard against the decline of its fishery. Until recently, if they didn’t catch fishermen in the act they had no means to prove illegal actions. This emboldened captains to take the same risk that the Chinese captain attempted, weighing the odds that Prefectura Naval’s patrol boats can’t cover the entire coastline.

“Before, we had to investigate all the ships,” said Ernesto Miguel Klocker, director of informatics and communications at Prefectura Naval. “Now, we receive an alarm when a ship enters our waters.”

A New Season

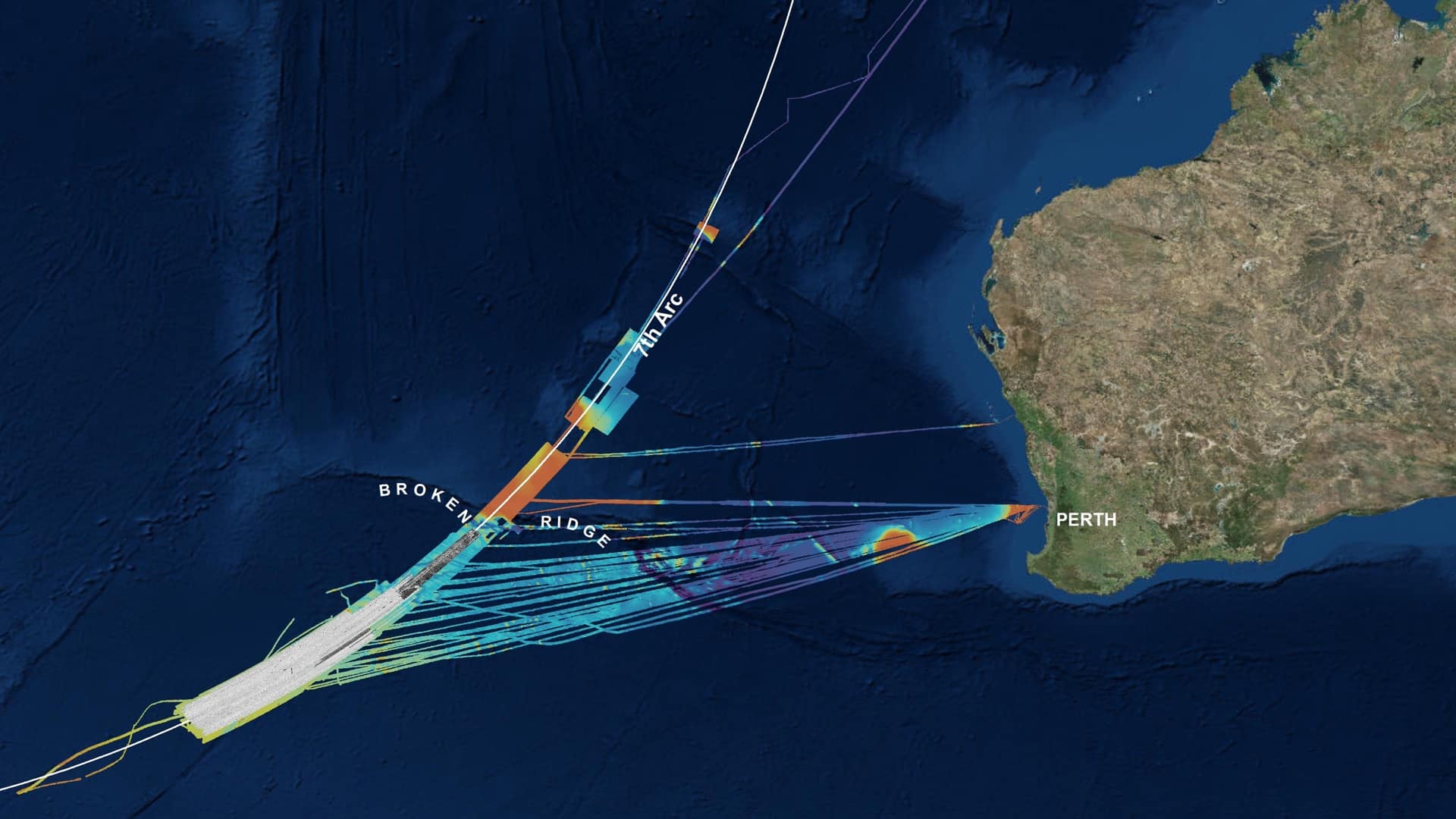

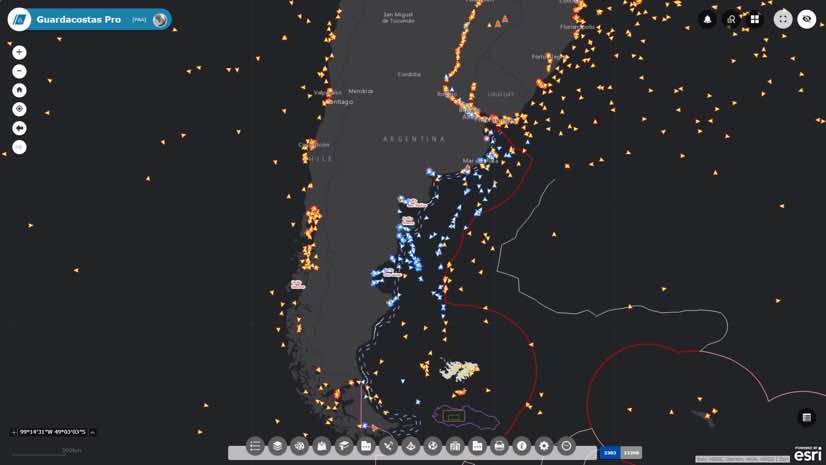

Prefectura Naval recently launched a real-time tracking system called Guardacostas Pro that combines vessel signals and satellite imaging. This system is what allowed Prefectura Naval to detect and chase the Chinese vessel in February, and to capture many other unauthorized ships throughout the season.

Along with this system, Prefectura Naval keeps a close watch on existing conditions, monitoring environmental variables and fish migration. This data and the activities of vessels guides immediate actions and long-term policy decisions.

The official squid fishing season typically starts on Feb. 1, however, this year the start was moved to Jan. 10 in response to hundreds of ships gathering outside the EEZ. Armed with its new system, Prefectura Naval can act quickly when poachers enter its waters.

“This year, when a Spanish vessel entered into our EEZ for a short time and returned into international waters, we could track it,” Klocker said. “This allowed us to catch the ship and escort it to port where it was impounded until a fine of 7.5 million pesos (roughly $360,000) was paid. The cargo of processed fish, worth roughly $380,000, was also confiscated.”

The Spanish captain had little recourse to refuse the fine because Prefectura Naval had the data to prove it.

Before people would say Argentina has little control of the sea. Now, word is getting out about our tracking system and it is harder for offenders to try to fool us.

Sound the Alarm

Now, anytime a vessel illegally enters the EEZ, the Guardacostas Pro system sounds an alarm and Prefectura Naval ships rush to confront the intruder.

The system takes in signals from the automatic identification system (AIS), a radio signal that each vessel transmits in order to avoid collisions. Data feeds come from 40 AIS receiving stations Prefectura Naval maintains onshore and from two companies, exactEarth and Orbcomm, that have satellites capturing signals on a global scale. Transmissions provide the vessel type, flag, location (latitude and longitude), speed, and course of every vessel.

AIS data alone proved insufficient as international rules don’t require all vessels to have this system. The system also integrates feeds from a satellite fishing monitoring system, a long-range identification and tracking system, and radio reports from the ships operating in the EEZ.

In addition, automated workflows process satellite-based synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery, ideal for detecting vessels because it cuts through clouds and darkness. The images expose a vessel’s size, and if it’s moving, its wake which can reveal its speed and direction. Prefectura Naval processes 250 SAR images per month to cover more than 200,000 square kilometers of the EEZ boundary every day.

Multiple inputs fused in a central geographic information system (GIS) improve accuracy for Guardacostas Pro. It also helps detect whether a vessel turned off AIS to stop transmitting its position—a common tactic of those intent on poaching.

Added awareness changed everything for Prefectura Naval.

“As of five years ago, we had very little information about the use of our seas,” Klocker said. “Now we have a good picture, which gives us electronic control of the sea, allowing us to send our air and naval units directly to the places where ships operate.”

Declining Stocks

The Guardacostas system serves a dual purpose of guarding the country’s economic and environmental interests.

More than poachers threaten the ocean’s fish supply. Modern fishing practices, with factory ships that process and immediately flash freeze their take, have damaged once-abundant fisheries. Techniques include miles-long driftnets, longlines baited with thousands of hooks, and the thousands of hooks deployed on automated winches. Industrial ships transfer tons of squid to huge refrigerator ships and get refueled and resupplied at sea so that they can fish without pause. It takes a toll.

In Argentina, fishery researchers and managers suggest that as much as 300,000 tons of Illex argentinus are harvested by unlicensed and unregulated fishing vessels every year. Prefectura Naval has turned to its new system to not only catch poachers in the act but also to amass data that tracks the activities of vessels over time. On average, it processes 1,000 records per second, performing eleven different analysis functions for the information in real time. In less than six months, the database has recorded more than 3.5 billion vessel positions. This data allows it to reconstruct old incidents or use historical information to discover new patterns.

Now that Prefectura Naval has a solid system for the sea, it moved this capability on shore. The system has become a multi-agency tool to aid the Ministry of Security’s homeland security mission.

Prefectura Naval cooperates with other federal forces: the federal police, the airport security police, and the Gendarmería (the National Guard). It tracks the location of all operating units through mobile phones, radios, vehicles with location sensors, and search and rescue aircraft. Knowing the last position of a ship or unit, regardless of the sensor or the system that reports it, gives the Ministry of Security a new security capacity with full awareness of the deployment of its staff.

“Before people would say Argentina has little control of the sea,” Klocker said. “Now, word is getting out about our tracking system and it is harder for offenders to try to fool us.”

Explore the many ways that GIS supports public safety with smarter situational awareness.