June 27, 2018

Deep in the Guatemalan jungle, a team of researchers from the Foundation for Maya Cultural and Natural Heritage recently made an exciting discovery at a 1,500-year-old settlement. Working across an 800 square-mile area, archaeologists did not need spades and wheelbarrows to unearth this find. Instead they used an aerial laser-scanning method known as LiDAR to see beneath dense layers of tree canopy and vines to get a landscape view of Mayan cities, agriculture, and transportation networks.

This 3D archaeological mapping effort revealed thousands of previously unknown structures including houses, irrigation canals, agricultural fields, defense works, and pyramids. By putting the imagery together on a map of the entire Maya lowlands, the team updated all prior understanding of the region and its ancient population. In fact, they revealed that the area was once home to as many as 10 million people.

Archaeologists are increasingly turning to technologies such as LiDAR and digital maps to learn about the past. The large-scale digs such as those that uncovered the secrets hidden in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings aren’t practical from a cost and logistics perspective, and a lot can be learned without lifting a shovel or trekking across the globe.

A Southwestern Cyber Dig

A similar effort is underway in the US states of Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. Like the Maya lowlands of Guatemala, the currently uninhabited region of the US Southwest was once home to thriving communities of native peoples.

CyberSW, a three-year project funded by the National Science Foundation, aims to consolidate massive amounts of data from thousands of related digs in the area. The project will bring history to life, making it available to researchers and the public through an online archive. Although the Native Americans left no written records, the stories of their existence are written in the ground to be detected by sensors and explored through maps and databases.

By looking at past patterns of human migration across landscapes to form communities, we can draw insight into current patterns of immigration, inequality, and overpopulation. This higher level of analysis will also help researchers understand climatic shifts that led people to abandon historic settlements.

High-Tech Tools

As archaeology moves deeper into the digital age, researchers are finding new ways to explore and (virtually) unearth the past, such as:

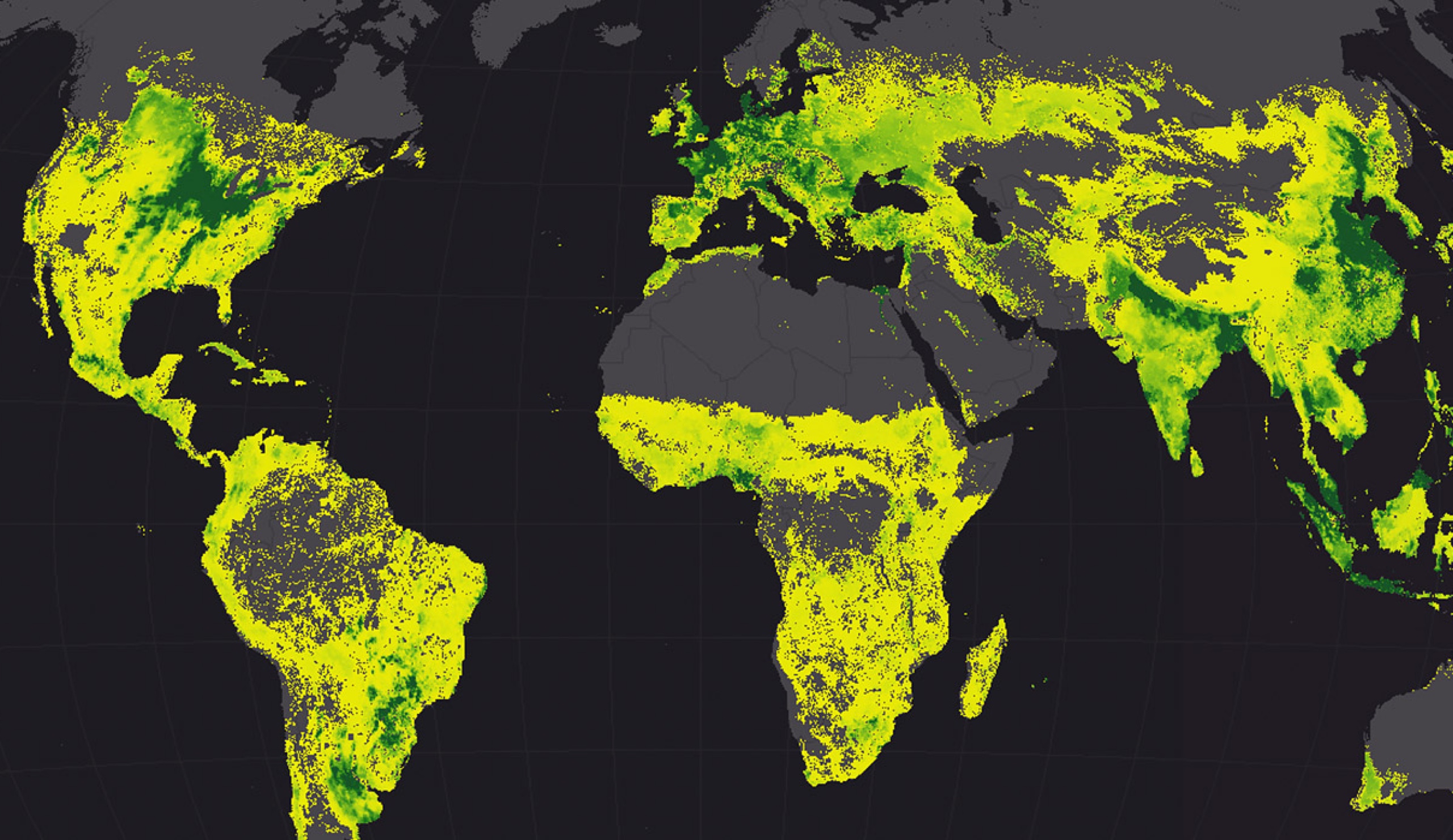

Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR): Bouncing laser light off the ground at an intensity that can penetrate dense vegetation reveals a detailed view of the Earth’s surface. The resulting 3D map allows researchers to see and share a larger landscape view, seeing what others can’t see.

Thermography: Using thermal infrared cameras on drones provides images that can help locate buried architecture and cultural landscape elements. The temperature returns from different materials and soil densities can reveal the outlines of long-removed buildings or the compacted lines of past pathways.

Ground-penetrating radar: Radar pointed at the ground locates subsurface objects and layering, providing a 3D model that maps the returns at different depths. These 3D underground maps prove particularly useful in finding burial sites that archaeologists would rather leave untouched.

Magnetometry: Every kind of material has unique magnetic properties. Sensing variations in the Earth’s magnetic field can help detect and map artifacts and features. Magnetometers react strongly to burned soil, brick, iron, steel and many types of rocks.

GIS: Geographic information systems allows people to visualize and explore all kinds of data. Increasingly, archaeologists use GIS tools and modeling software such as Esri’s CityEngine to create virtual replicas of ancient civilizations. Models can be explored via immersive virtual reality, allowing anyone to walk through the past without traveling to distant sites.

Changing Evidence

Archaeologists face a stereotype that focuses on digging and ignores the field’s broader mission: To study how people lived and adapted over time, and to learn why cultures come and go.

Much of today’s archaeological research involves deeper explorations of known sites and broader research into networks of sites. Digitized records make it easier for researchers to learn about past discoveries and build their knowledge base. New technologies such as sensors, databases, and GIS maps provide visualization and more profound interdisciplinary awareness.

While fieldwalking hasn’t entirely faded to the past, archaeologists can cover far more ground and gain greater insights by deploying digital tools. And, as was the case in Guatemala and the desert Southwest, researchers can use technology to discover new aspects of areas they have been working in and walking over for decades.

To learn more about the tools and workflows used for digital archaeology, read this article. Immerse yourself in a recent exploration by viewing a live story map of the dig at the Sandby borg ring fort located on the island of Öland, Sweden.