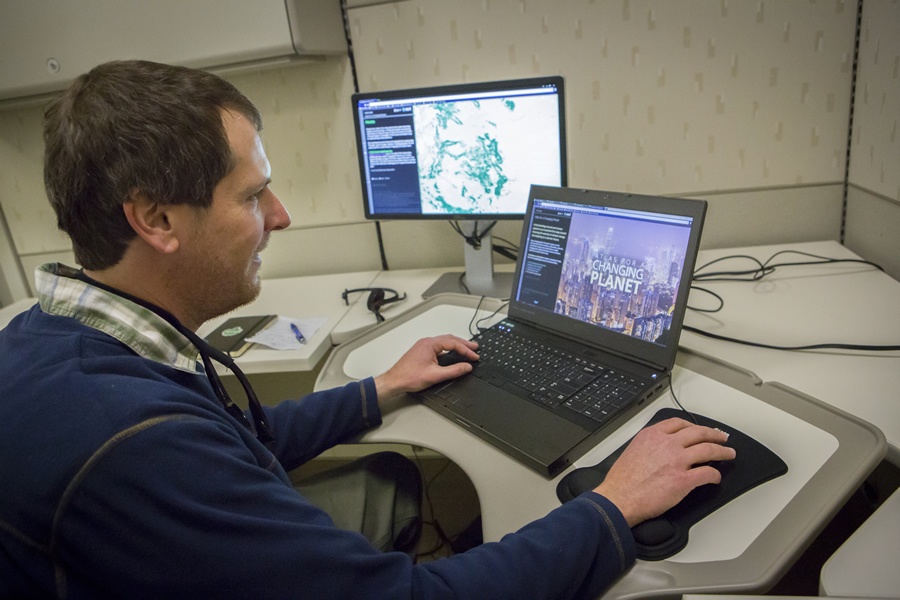

Shane C. Matthews sees geographic knowledge as a force for good. That’s why, in his role as a cartographic specialist at Esri, he scours the planet for high-quality, authoritative maps and imagery that will become building blocks for the Living Atlas of the World—what Clint Brown, Esri’s director of product engineering, likes to call “the GIS of the world.”

It’s also why, in his role as a father, Matthews acts as a kind of geo Jedi to his two-year-old son, Miller, giving him a good grounding in geography. He reads Miller bedtime stories like There’s a Map in My Lap! and together they play with map puzzles.

“The poor kid is destined for a life of geography,” joked Matthews, 45, whose wife is a geographer too. “He’s my young apprentice.”

Matthews grew to love geography on his own. His passion was ignited when he took a physical geography class in college. He worked for 12 years at the National Geographic Society, initially as a production cartographer creating and editing map products. Later, in his role as a product manager, Matthews oversaw the development of the Trails Illustrated Topographic Maps and the Adventure Travel Maps series. He joined Esri in 2011.

Today, based in Esri’s Colorado office, Matthews counts himself lucky, as he gets to do what he’s clearly passionate about: hunt for the best maps and imagery available to expand and enrich the Living Atlas of the World.

According to Brown, Matthews is helping spearhead the effort to encourage Esri ArcGIS technology users to contribute to and use Living Atlas of the World content.

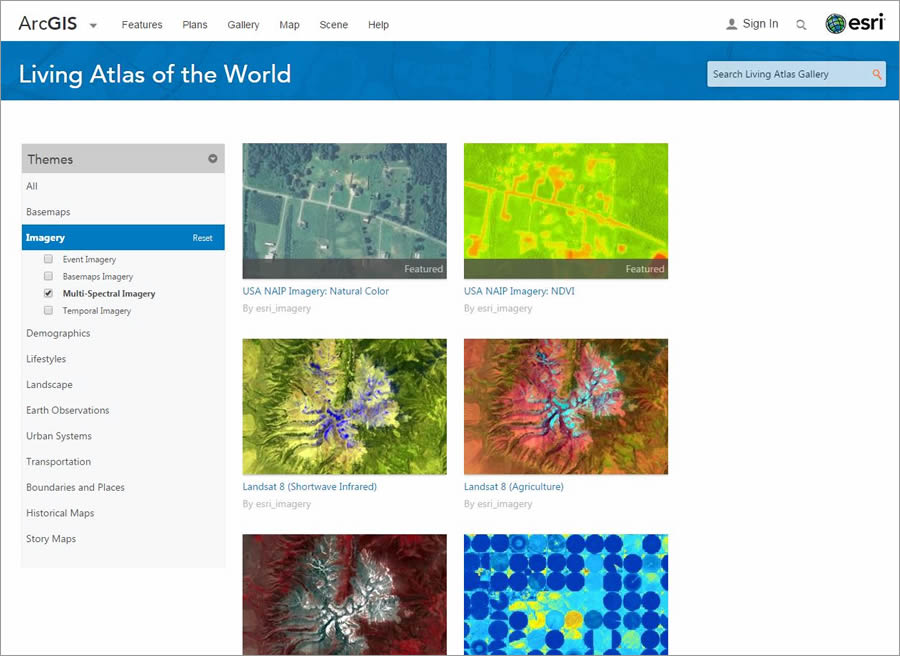

Years in the making, this vast and evolving online repository of authoritative maps currently contains more than 4,000 items including basemaps, imagery, historical maps, Story Maps, and layers. Also included are maps with information on demographics; lifestyles; boundaries; the landscape; traffic; transportation systems; and earth observations such as precipitation, snowfall, and earthquakes.

While Esri contributes content, so do many government organizations, Esri partners, and others from the Esri ArcGIS community of users. Matthews works directly with contributors, explaining the benefits of contributing to the Living Atlas of the World. For example, Esri will process the contributors’ raw imagery and host the content in the cloud, giving all participants easy, on-demand access.

“I enjoy talking to people, and I like to look at maps all day,” said Matthews, a Virginia native and outdoor enthusiast who earned a bachelor of science degree in geography from Appalachian State University in North Carolina. “I like talking about maps and evangelizing maps and creating maps when I can.”

Matthews has worked with government organizations such as the City of Fargo, North Dakota, which contributed high-resolution imagery to the Living Atlas of the World. The imagery is served using Esri’s secure commercial-grade cloud services, giving organizations that collaborate with the city, such as the US Army Corps of Engineers, easy access to the imagery.

In the coming months, Matthews will work with the Esri distributor in Brazil to obtain imagery of the venues for the 2016 Summer Olympics in Brazil. Esri will also try to obtain high-resolution imagery of Time Warner Cable Arena in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Quicken Loans Arena in Cleveland, Ohio, which will host the Democratic National Convention and the Republican National Convention, respectively. Matthews said that this type of content could be used in web mapping apps created by trip planners, security personnel, or the events’ vendors.

“Shane’s a real go-getter,” said Seth Sarakaitis, Esri Community Maps Program manager and Matthews’ supervisor. “His background in cartography provides a solid foundation for one of Shane’s many roles at Esri, as a curator of Living Atlas content. He has a keen eye for identifying interesting maps and applications and recognizes those maps whose authors took the extra effort to get noticed.”

Growing Up Spatially Aware

How Matthews became a cartographer with a keen eye for a good map begins in Richmond, Virginia, where he and his younger brother were raised. Richmond is a city steeped in American history. During the Revolutionary War, the famous American defector Benedict Arnold led British troops in a successful attack on the city in 1781. Also, Richmond was the capital of the Confederate States during the Civil War.

While Matthews’ father and mother weren’t geography buffs, they nurtured their elder son’s interest in history. His father took the two boys, both in grade school at the time, to famous colonial and Revolutionary and Civil War sites on weekends, including Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Appomattox.

“Appomattox is significant. That’s where [Confederate Army General] Robert E. Lee folded it up and surrendered officially. Papers were signed,” Matthews said. “I’ve been in that building. I’ve seen those chairs and desks” where Lee and Union Army general Ulysses S. Grant sat.

Visiting historic sites and monuments near his hometown helped Matthews better understand the geographic context of the events that occurred. “I was really interested in history,” he said. “Being able to visit these places was really awesome.”

While weekend outings to historic sites helped Matthews understand where he lived relative to other places in Virginia, a road trip to see his grandparents in Columbia, South Carolina, introduced him to maps.

“Back then, the speed limit on the interstate was 55 miles per hour. It would take forever to get there—eight hours,” Matthews recalled. “My dad kept an atlas in the back of the car. Maybe it was because I was wondering how long I would have to deal with this, but I would pick up the atlas and look at the signs, and then use the map to figure out where I was and how long it might be before this [trip] was over. I think that’s when I became a lover of maps.”

Years would pass, however, before mapping as a profession entered Matthews’ consciousness.

Dirt, Rocks, and Trees

Matthews says he was just an average student in high school. Unsure of what to do with his life, he drifted through several colleges (and jobs waiting tables) before enrolling in Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina. Even his attraction to the community of Boone foreshadowed his interest in geography. Matthews liked to hike in the mountains nearby.

He loves the mountains, which is why he enjoys living today in Colorado. “I just think flat is boring,” he said. “I like the beach. I like the desert. I like things with visual appeal. I just like topography in my life.”

Matthews might have never ended up in Colorado if he hadn’t attended Appalachian State University, which required that students take a physical geography course to graduate.

“The class was Soils, Landforms, and Vegetation,” Matthews said. “We called it Dirt, Rocks, and Trees. That course dealt with geology and geomorphology, weather and climate, how mountains are formed, how rivers and watersheds behave, and how the physical environment works. For some reason, I found that fascinating.” Hooked, Matthews became a geography major; started making As instead of Cs; and even took a GIS course, where he was introduced to Esri’s early ArcInfo software.

Mapping Out a Career in Cartography

After a stint as a data analyst and geographer at a regional council of governments in North Carolina, Matthews moved to Colorado, where he took a job as a seismic data specialist for the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

The National Geographic Society hired him as a cartographer in 1999 to work on the society’s line of recreational trail and adventure maps. During his dozen years there, he learned map production from top to bottom—from assigning line styles and specifications to editing maps, and from gathering content (e.g., rivers, trails, parking lots, campsites) from land management agencies to placing the information into GIS as part of the initial production process. Later, Matthews took on a managerial role, supporting the budgeting process and providing information for press releases about the maps being created in the Colorado office.

Like his position at National Geographic, Matthews’ job today largely involves evangelizing the importance of data sharing. He jokes that he’s good at begging for data. This is likely why he’s editor of Esri News for the Living Atlas Community, an email newsletter that encourages sharing content for the Living Atlas, keeps readers informed about new content, and shows them how that content can be transformed into useful web maps and apps.

Doing His Part to Increase Geographic Literacy

Matthews lives and breathes geography, which is why he finds it alarming that geographic literacy among Americans seems to be waning. Learning geography is not just about knowing where places are located on a map, said Matthews. “Understanding geography,” he said, “means having a good understanding of different cultures, countries, economies, and social systems.”

He recently heard about the 2015 report issued by the United States Government Accountability Office that said that almost 75 percent of eight graders scored at levels below proficient in geography. “It’s disappointing,” said Matthews. Social studies and geography were core subjects at his school. “It seems that [geography has] lost its importance to educators or the folks who design the curriculum. I’m not sure why.”

So he’s doing his part to counter the trend. Matthews will soon start to volunteer with the Outdoor Lab Foundation, based in Colorado. The nonprofit organization gives all sixth-graders in Jefferson County, where he lives, the opportunity to spend one week living in a camp, learning outdoor skills such as trail building and applying academics in a wilderness setting.

Matthews said he would like to help kids build the trails, and then teach them how to create story maps of the trail system, with points of interest along the way highlighted with photographs and videos.

At home, Matthews does his best to make sure his son, Miller, knows his geography. “Map” was one of the first words Miller learned. Mom and dad bring him reading material such as the National Geographic Kids Beginner’s World Atlas.

Miller also plays with a 24-piece world puzzle that is emblazoned with the flora and fauna of the continents. “He learns where things are and what type of animals and plants live there,” said Matthews. Miller can see that moose roam Canada and chimpanzees live in Africa.

Two-year-olds being two-year-olds, however, means that the world of puzzle pieces is not always a perfect place. “I usually put it together, and he likes to rip it up,” Matthews said, smiling.

On some level, though, Matthews believes the information sinks in. He and his wife put a globe in the foyer outside Miller’s bedroom, and when the boy is brushing his teeth, Matthews points out countries on the globe. “I will tell him where we are and where our families are,” he said. “He will recognize a place that I show him even days later.”

Before his son was born, Matthews found a special map on a website that sells maps. A friend who works for that site presented a gift to the family. Today, the Miller Cylindrical Projection map hangs on the boy’s bedroom wall. That really delights dad.

“The satisfying thing is, when I wake him up, he points to the map and says, ‘Map,’ ” said Matthews. “I don’t think he appreciates a map as an information product, but I think, eventually, he will get that.”