It isn’t rare for Tom Hebert to pick up his phone and hear: “I found a dinosaur. Can you come dig it up?”

It isn’t rare for Tom Hebert to pick up his phone and hear: “I found a dinosaur. Can you come dig it up?”

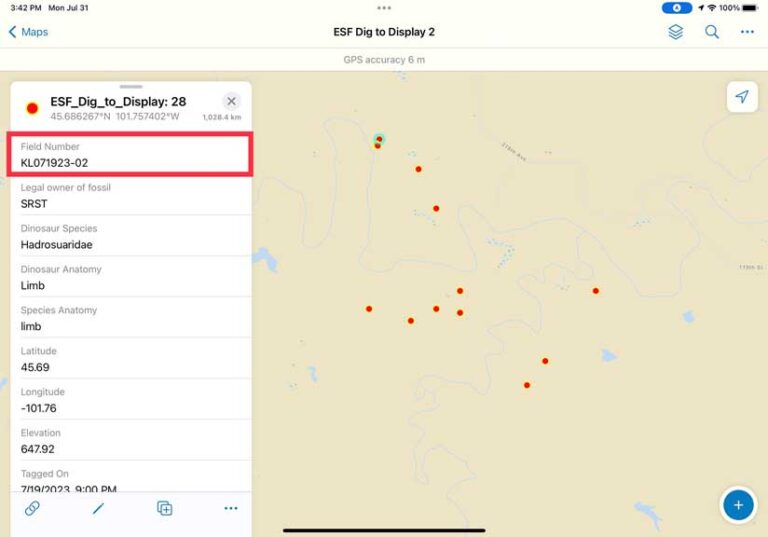

Through partnerships with technology companies, Hebert is using RFID tags and GIS mapping to track and document dinosaur fossils with the goal of creating a shared map displaying discoveries worldwide. [RFID (radio-frequency identification) tags use radio frequencies to transfer data that uniquely identifies an object, person, or animal and can be used to track its location.]

From his home in Wisconsin, Hebert has spent 14 years driving to and from the dinosaur fossil-filled ranges in South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming for digs. Lately, he has also been visiting museums to create a digital record of fossils on display or in storage. His goal is to transform the way museums manage fossils and other assets, using digital tools that include ArcGIS Survey123, a location-aware data collection app, and InfraMarker, an RFID tracking technology.

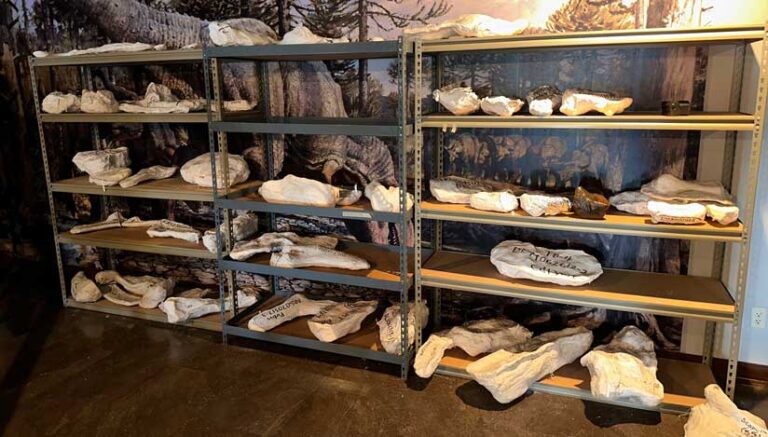

Often only a fraction of a museum’s collection is on display at any given time. Most of the collection is stored behind the scenes on shelves, in drawers, and sometimes in off-site warehouses. The work of collecting, identifying, and displaying artifacts has long relied on handwritten notes and printed records. Keeping track of artifacts is challenging, even for the largest museums. It’s no wonder, then, that audits have revealed pieces that have gone missing or have been damaged or stolen.

Researchers at the Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation, which funds the Integrated Digitized Biocollections site, see value in digitizing records of collections. Such records would make it easier to answer critical questions about our Earth, including how the estimated 22 percent of remaining species recovered from the mass extinction event 66 million years ago that annihilated the remaining dinosaurs.

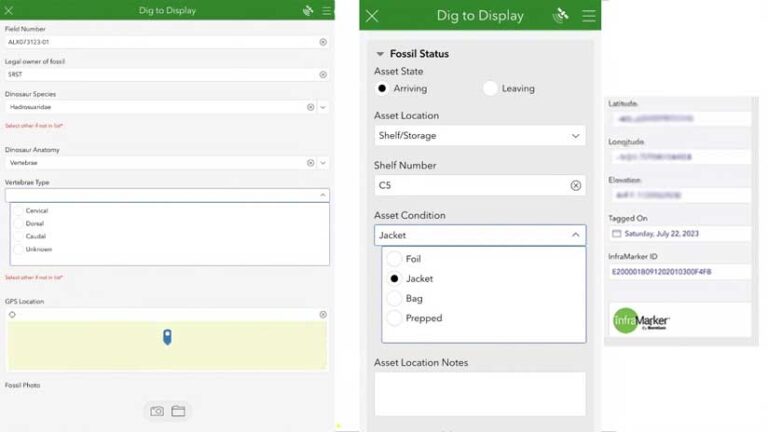

By attaching RFID tags to fossils, Hebert can track specimens from dig sites to warehouse shelves, to where they are cleaned and prepared and placed on display. This new awareness of fossil location—including near real-time tracking while in transit—provides a map-based audit trail that Hebert likes to call “dig to display.” It’s the first step in what he hopes could become a single shared map showing where many of the world’s dinosaur bones have been found and where they are now. Hebert also thinks the RFID technology paired with a map could be a tool for federal regulators to monitor the excavation permits they issue on some of the millions of acres of land they oversee.

It’s a continuation of Hebert’s mission to make dinosaur excavating accessible to more people of all ages, especially military veterans and children, whom he invites to join his digs on private property.

“Dinosaurs are how we get kids into science,” he said. His youngest daughter is the reason he started digging. She wanted to go on a fossil hunt, so Hebert found a group that offered trips in South Dakota. That is where he fell in love with the activity. His daughter is now studying to be a marine biologist.

From Insurance to Fossils

Before Hebert began venturing to rocky landscapes each summer to dig for fossils, he owned an insurance agency. He used GIS to find out about the locations he was insuring.

When he returned to school in fall 2020, he had an aha moment sitting in a GIS class at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire.

“Wait a minute, why can’t we do this with dinosaur bones as we’re digging them up?” he thought.

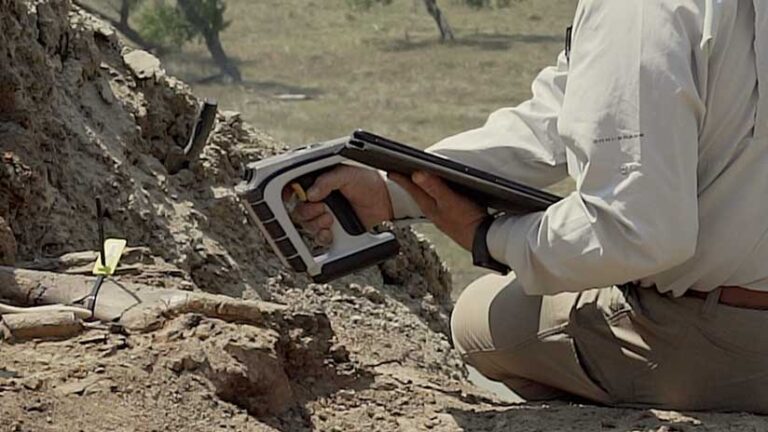

That simple question turned into a research project and a request to borrow tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of the geography department’s mapping equipment. When the department said no, Hebert partnered with companies that were willing to lend him their technology. One company was Esri partner Carlson Software. The company’s field software and hardware are typically used for land surveying, civil engineering, construction, and mining.

Hebert reached out to Ladd Nelson, the company’s Midwest sales director. Nelson, who was fascinated by dinosaurs while growing up, said that the proposal captured his inner child. When Hebert explained what he wanted to do, Nelson was confident that Carlson had the equipment that could help him.

“We’ve tried to show people that Carlson can do much more than surveying and engineering,” Nelson said. “The word is getting out there that we can help organizations get all their geographic databases online and populated with highly accurate location information to ensure they not only know where their assets are now but can more easily find them again in the future.”

Or, in the case of dinosaur fossils, where they were first uncovered before being moved to storage or museums.

Recording Fossils on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation

Hebert crossed paths with Esri partner Berntsen, the maker of the InfraMarker RFID tagging technology, in the exhibit hall at the Trimble Dimensions conference in 2022. This encounter led Hebert to test Berntsen’s InfraMarker RFID solution during digs in 2023 on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, which encompasses more than 3,500 square miles and straddles the border between North Dakota and South Dakota.

“It’s all solving the same problem: how do you connect assets to a map?” said Mike Klonsinksi, president of Berntsen. Whether it’s an underground pipe or a dinosaur bone, in GIS, it’s an asset with a location.

Museum archivists and curators are generally reticent about physically handling their valuable specimens and pieces for fear of damage. RFID scanning can be done from a distance to inventory a collection. If someone on staff can’t find an item where it’s supposed to be, larger areas can be scanned to detect it. In addition, RFID antennas can be positioned in areas where artifacts are regularly moved from storage to display or vice versa to track where each item is at any given time.

“For us, the biggest lesson here is, it’s not a dinosaur solution, it’s really an asset-to-GIS solution,” Klonsinski said.

For the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Hebert’s efforts have offered a way to better record information about the more than 10,000 existing fossils the tribe’s leaders will need to relocate to a temporary storage facility. “We need to secure the fossils we have,” said Fawn Wasin Zi, the tribe’s outgoing director of reservation resources. In Hebert, the tribe members found a paleontological partner willing to donate his time to protect their fossils, Wasin Zi said.

Hebert and his team found and tagged about 50 new fossils in the field and created digital records for several hundred more in the tribe’s existing collection.

He is in the second year of a five-year agreement with the tribe that will be allow him to excavate fossils on the tribe’s land after permits are sought and secured from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Any fossils found are named and kept by the tribe. Hebert’s goal is to eventually help create an exhibit for a cultural museum that will be built on the tribe’s land.

At the Museum of Discovery at Sheridan College in Wyoming, Hebert and the museum’s directors spent five days in January 2024 cataloging about 700 fossils. Using ArcGIS Survey123 and ArcGIS Field Maps, they manually entered handwritten GPS coordinates that recorded where each specimen was found and attached an RFID tag to each one. Now a digital record will show if that fossil is on a shelf, on display, on a researcher’s desk, or loaned to another museum.

Hebert is also adding contextual metadata to each fossil, including images, chemical information to determine the age, research paper links, and other resources. Determined to digitize the information that’s normally been handwritten on index cards and stored in museum cabinets, Hebert wants to make the data and fossils easier to access.

“Cards get lost, cards get damaged, and reading handwriting is often impossible,” he said. Stored in the cloud and pinpointed on a map, digital records promise to reveal more about the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods, when dinosaurs roamed the land. Dusting off records and bones and digitizing them to relate their origins could safeguard essential data about where dinosaurs lived and died, helping lead to better understanding about Earth’s origins and changes over time.

From his home in Wisconsin, Hebert has spent 14 years driving to and from the dinosaur fossil-filled ranges in South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming for digs. Lately, he has also been visiting museums to create a digital record of fossils on display or in storage. His goal is to transform the way museums manage fossils and other assets, using digital tools that include ArcGIS Survey123, a location-aware data collection app, and InfraMarker, an RFID tracking technology.

Often only a fraction of a museum’s collection is on display at any given time. Most of the collection is stored behind the scenes on shelves, in drawers, and sometimes in off-site warehouses. The work of collecting, identifying, and displaying artifacts has long relied on handwritten notes and printed records. Keeping track of artifacts is challenging, even for the largest museums. It’s no wonder, then, that audits have revealed pieces that have gone missing or have been damaged or stolen.

Researchers at the Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation, which funds the Integrated Digitized Biocollections site, see value in digitizing records of collections. Such records would make it easier to answer critical questions about our Earth, including how the estimated 22 percent of remaining species recovered from the mass extinction event 66 million years ago that annihilated the remaining dinosaurs.

By attaching RFID tags to fossils, Hebert can track specimens from dig sites to warehouse shelves, to where they are cleaned and prepared and placed on display. This new awareness of fossil location—including near real-time tracking while in transit—provides a map-based audit trail that Hebert likes to call “dig to display.” It’s the first step in what he hopes could become a single shared map showing where many of the world’s dinosaur bones have been found and where they are now. Hebert also thinks the RFID technology paired with a map could be a tool for federal regulators to monitor the excavation permits they issue on some of the millions of acres of land they oversee.

It’s a continuation of Hebert’s mission to make dinosaur excavating accessible to more people of all ages, especially military veterans and children, whom he invites to join his digs on private property.

“Dinosaurs are how we get kids into science,” he said. His youngest daughter is the reason he started digging. She wanted to go on a fossil hunt, so Hebert found a group that offered trips in South Dakota. That is where he fell in love with the activity. His daughter is now studying to be a marine biologist.

From Insurance to Fossils

Before Hebert began venturing to rocky landscapes each summer to dig for fossils, he owned an insurance agency. He used GIS to find out about the locations he was insuring. When he returned to school in fall 2020, he had an aha moment sitting in a GIS class at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire.

“Wait a minute, why can’t we do this with dinosaur bones as we’re digging them up?” he thought.

That simple question turned into a research project and a request to borrow tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of the geography department’s mapping equipment. When the department said no, Hebert partnered with companies that were willing to lend him their technology. One company was Esri partner Carlson Software. The company’s field software and hardware are typically used for land surveying, civil engineering, construction, and mining.

Hebert reached out to Ladd Nelson, the company’s Midwest sales director. Nelson, who was fascinated by dinosaurs while growing up, said that the proposal captured his inner child. When Hebert explained what he wanted to do, Nelson was confident that Carlson had the equipment that could help him.

“We’ve tried to show people that Carlson can do much more than surveying and engineering,” Nelson said. “The word is getting out there that we can help organizations get all their geographic databases online and populated with highly accurate location information to ensure they not only know where their assets are now but can more easily find them again in the future.”

Or, in the case of dinosaur fossils, where they were first uncovered before being moved to storage or museums.

Recording Fossils on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation

Hebert crossed paths with Esri partner Berntsen, the maker of the InfraMarker RFID tagging technology, in the exhibit hall at the Trimble Dimensions conference in 2022. This encounter led Hebert to test Berntsen’s InfraMarker RFID solution during digs in 2023 on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, which encompasses more than 3,500 square miles and straddles the border between North Dakota and South Dakota.

“It’s all solving the same problem: how do you connect assets to a map?” said Mike Klonsinksi, president of Berntsen. Whether it’s an underground pipe or a dinosaur bone, in GIS, it’s an asset with a location.

Museum archivists and curators are generally reticent about physically handling their valuable specimens and pieces for fear of damage. RFID scanning can be done from a distance to inventory a collection. If someone on staff can’t find an item where it’s supposed to be, larger areas can be scanned to detect it. In addition, RFID antennas can be positioned in areas where artifacts are regularly moved from storage to display or vice versa to track where each item is at any given time.

“For us, the biggest lesson here is, it’s not a dinosaur solution, it’s really an asset-to-GIS solution,” Klonsinski said.

For the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Hebert’s efforts have offered a way to better record information about the more than 10,000 existing fossils the tribe’s leaders will need to relocate to a temporary storage facility. “We need to secure the fossils we have,” said Fawn Wasin Zi, the tribe’s outgoing director of reservation resources. In Hebert, the tribe members found a paleontological partner willing to donate his time to protect their fossils, Wasin Zi said.

Hebert and his team found and tagged about 50 new fossils in the field and created digital records for several hundred more in the tribe’s existing collection.

He is in the second year of a five-year agreement with the tribe that will be allow him to excavate fossils on the tribe’s land after permits are sought and secured from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Any fossils found are named and kept by the tribe. Hebert’s goal is to eventually help create an exhibit for a cultural museum that will be built on the tribe’s land.

At the Museum of Discovery at Sheridan College in Wyoming, Hebert and the museum’s directors spent five days in January 2024 cataloging about 700 fossils. Using ArcGIS Survey123 and ArcGIS Field Maps, they manually entered handwritten GPS coordinates that recorded where each specimen was found and attached an RFID tag to each one. Now a digital record will show if that fossil is on a shelf, on display, on a researcher’s desk, or loaned to another museum.

Hebert is also adding contextual metadata to each fossil, including images, chemical information to determine the age, research paper links, and other resources. Determined to digitize the information that’s normally been handwritten on index cards and stored in museum cabinets, Hebert wants to make the data and fossils easier to access.

“Cards get lost, cards get damaged, and reading handwriting is often impossible,” he said. Stored in the cloud and pinpointed on a map, digital records promise to reveal more about the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods, when dinosaurs roamed the land. Dusting off records and bones and digitizing them to relate their origins could safeguard essential data about where dinosaurs lived and died, helping lead to better understanding about Earth’s origins and changes over time.