A South Korean city is using a digital twin to become a truly smart city by using its geospatial infrastructure to engage its agencies and the public to help meet challenges, both present and future.

Incheon Metropolitan City, one of the largest cities in the Republic of Korea, is home to three million people and a sizeable population of mosquitoes. Exactly how many of the latter is difficult to say, but it is a question that interests the country’s public health officials.

Located on the northwest coast of South Korea, near Seoul, the nation’s capital, Incheon is a major industrial center. Incheon anchors the western side of the Seoul Capital Area, the world’s second-largest megaregion. As the world continues to urbanize, the region will get more crowded.

In this age of global pandemics, Incheon is also the gateway city to South Korea, with one of the world’s busiest international airports. “Due to the growth of overseas travel and global logistics, Incheon needs to be very careful about infectious diseases,” said Jo Gi-woong, a GIS expert who oversees Incheon’s smart city initiatives.

In recent years, South Korea has experienced an uptick in dengue fever, which is carried by mosquitoes. Warming in the region caused by climate change intensifies the threat of other foreign mosquito-borne diseases, including malaria, yellow fever, West Nile fever, and Japanese encephalitis.

Downtown Incheon was the representative urban area in a recent study that examined how climate change is affecting the mosquito population on the Korean peninsula, and whether there was a correlating effect on disease spread. For three years, a monitoring system logged mosquito captures, transmitting the real-time data over a Long-Term Evolution (LTE) network to ArcGIS GeoEvent Server. [LTE is a 4G wireless broadband standard that is used by mobile devices to connect to the internet from cellular towers.] System data can be cross-referenced with other geographic data, such as real-time feeds from the national weather service.

“We’re using an ArcGIS dashboard to monitor all this data together,” Jo said. “We share the information with related agencies to quickly identify vulnerable areas, so that the problem can be intensively and preemptively controlled.”

On the question of whether climate change was creating more mosquito-borne illnesses, the study was inconclusive. But the monitoring system itself was an example of an extraordinarily forward-thinking smart-city experiment unfolding in Incheon. Under Jo’s leadership, the city has built a digital twin, which was introduced in early 2021.

Digital twins are virtual representations of the processes, relationships, and behaviors of real-world systems. The concept began as a way for manufacturers to record and log the intricate functioning of factories. Industrial designers began to use digital twins to visualize the effect of proposed changes to an object or process.

More recently, the digital twin concept has been applied to urban planning. Virtual 3D models of cities, augmented by local information, provide a means of proposing, understanding, and analyzing development projects and other changes to the urban landscape.

Incheon’s digital twin attempts to mirror many of the city’s functions in real time. The real-world system it duplicates is nothing less than Incheon itself. In this context, mosquitoes are not just pests and disease vectors; they represent one more dynamic system in a city that contains many, ranging from power grids to weather activity. To varying degrees, these systems all affect—and are affected by—the others. The digital twin is an ongoing record of the processes and interactions of these systems.

The use of GIS for government functions in South Korea dates back to the 1990s, when several high-profile gas explosions revealed the need for greater understanding of underground critical infrastructure. “These disasters were caused by negligence in safety management and a lack of proper guidance,” Jo explained.

Municipalities across the country invested in GIS tools for surveying and mapping infrastructure, but not for gathering, sorting, and sharing data. For city managers, the costs of managing data were prohibitive.

Jo’s expertise combines land management, which he studied in the 1980s, and computer engineering, which he later pursued. The development of Internet of Things (IoT) sensors and strong mobile networks made gathering large amounts of location data a more realistic proposition.

In 2013, some civic offices in Incheon began to use web-based GIS. Eventually, 250 departments across the city were using some form of it. In 2016, Jo began doing GIS work for the city of Incheon. By 2018, a “data-based administration,” as Jo called it, was essential policy in Incheon. The next step, as Jo saw it, was to put all these departments on the same page using a digital twin.

As a first step toward that goal, Incheon’s smart city department oversaw the construction of a 3D basemap as the foundation for the city’s digital twin. “It’s all about the data, and we decided that for a digital twin, we needed very elaborate data to understand and capture a high-density city,” Jo explained. After considering several options, Jo’s team decided to capture precise point cloud data by using lidar to scan the entire city. That would produce data at a scale of 150 points or more per square meter.

Throughout the process of creating the digital twin, Jo and his team concentrated more on data creation and management, and less on developing a system architecture that was unique to the Incheon project.

“Some organizations, when building a digital twin, spend more on system development and the integration side than on the data,” he said. “But we decided to use web scenes. It’s not perfect for Korean conditions, but I think it’s the best solution, because the 3D basemap and data built by our city can be infinitely expanded.”

By the end of 2020, the virtual city was nearing completion, ready to become a true digital twin. Waterworks Headquarters Incheon Metropolitan City was the first local office to import its data into the digital twin. Using Portal for ArcGIS, a component of ArcGIS Enterprise, the department deployed a water utility network model and enabled web-service based architecture for the city’s water supply management system.

“The mobile era is overflowing with location information,” he said. “There is a convergence of data relating to temporal and spatial information, and the scope of use is expanding into all areas of local administration. There is so much data out there, from text data to large-capacity imagery data, but data that contains temporal and spatial information is like 100 percent pure gold.”

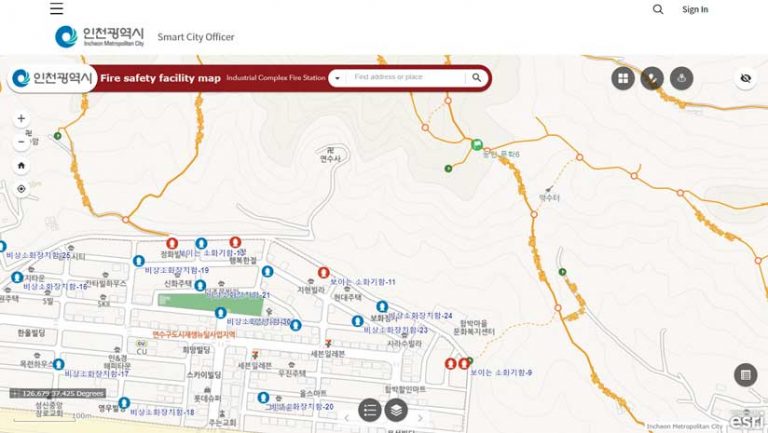

Since the beginning of the year, the Incheon digital twin has grown to include six project areas: fire response management, traffic, urban sanitation, facilities management, urban development, and city revitalization.

Activities for improvements include a method for routing and tracking the location of street cleaning vehicles, so that managers have a better understanding of progress at any given moment. By creating maps of garbage and food waste disposal throughout Incheon and monitoring its status through an app, the department can understand how to effectively allocate cleaning vehicles.

The Incheon Fire Department has used the digital twin to launch an experimental program for allocating resources. By outfitting 35 fire trucks with receivers that use an IoT network and GPS for precise real-time positioning, the department has the real-time location for each truck. “When the department is able to determine instantly where its resources are, it will definitely speed up response times,” Jo explained.

Incheon’s digital twin will soon be used to manage underground assets, such as sewer systems, power grids, telecommunications, and subways. Even natural gas lines—the impetus for introducing GIS into the urban management process in the 1990s—will be monitored and controlled with the digital twin.

Jo is particularly pleased that Incheon’s digital twin is now being used to operate a flood prediction monitoring system. This is an important development because the digital twin doesn’t just mirror the city as it is in the moment; it can be used to predict events caused by changes in conditions in the city.

“The ultimate model of a digital twin city,” he explained, “is a simulation based on the real world.”

Altogether, 500 staff members from 30 different departments currently use the digital twin in some capacity. Jo expects those numbers to grow as the complexity of the digital twin increases. “We are constantly collecting data, and we try to keep it as current as possible,” Jo said. He estimates that the digital twin has increased efficiency among Incheon city government offices by 10 percent. The next step in its evolution will be to begin making data from the digital twin more accessible to the public.

“We’ve realized that the more we engage constituents and connect data, the more we can reduce costs and make Incheon a more sustainable and prosperous city,” he said. “What really makes Incheon a smart city is that we’re creating a barrier-free zone with geospatial infrastructure. No matter what department, other agencies, as well as the private sector, can engage with us to help solve Incheon’s problems.”

As more of the digital twin becomes public facing, the mapping aspect and its GIS foundation will come to the forefront. Jo’s team is currently working on using the digital twin as the basis for mobile mapping apps.

The first of these apps is designed to support the local economy by focusing on Incheon’s 12 shopping areas in the older section of the city. The oldest of these markets is more than a century old. “There isn’t enough information about these old markets,” Jo said. “The lack of information about the types of stores, opening hours, and contact info has been a barrier, making it difficult for them to attract new customers.”

Incheon has worked with several prominent Korean companies to create maps of these markets. “As a result, people can now search for information about the stores, and even use GPS to find the exact store location,” Jo explained.

Generally, Incheon is not a city of young people. Nearly 30 percent of the population has limited mobility due to age or physical condition. To improve the city’s walkability and create a more pedestrian-friendly environment, Jo’s team is working on maps that are more than simple two-dimensional documents that flatten the city, both literally and figuratively.

“Maps help us find our way, but they don’t typically provide details about things that might be difficult for people, like a pedestrian overpass, elevated roads, or crosswalks that have a short signal duration,” he said. “Through data collection, we’ll publish maps that let people walk freely while avoiding obstacles like steep slopes and stairs.”

In a subtle way, these maps build on the premise that animates much of Jo’s work—that the gold standard for data merges a 3D spatial perspective that includes slopes, stairs, and overpasses with temporal information, such as intersections with lights that may change too quickly for slow walkers.

A city’s most dynamic system is always its people. In Jo’s formulation of the digital twin, people will have a place in the digital twin’s data. His dreams for its evolution, therefore, focus not merely on data, but on harnessing the power of the city’s residents to make the twin even more powerful.

For the moment, Jo’s smart city office has primary control over the digital twin, but in the coming years the digital twin will become a collaborative entity for all stakeholders. As he puts it, “all citizens will be part of this in the long run.”