You don’t need a geography degree to get paid to talk about using a geographic approach across industries or understand how to mitigate some of the most severe challenges of our time with GIS.

Psychology, sociology, anthropology, and epidemiology are a testament to this. The ologies were helpful to me. They set the stage—so to speak—by providing a viewpoint that sent my career path toward inquiry. Truthfully, long before academia, I had many questions about the world and our modern Western social system. Those questions explored where the system might have blocks, inefficiencies, and even gaps that lead to sickness and a lower quality of life for so many.

Because I had more questions than answers, I knew that school was the place I needed to go, so off to college I went. Although it seems like an obvious next step from high school, I started this journey as a dropout and then a teen mom, so college was not on my radar.

I was a hard worker, and the longer I worked—first in the service industry and then in social services—the more I kept accumulating more questions about our world and the state of our systems. In college, surrounded by the ologies, I began understanding that pattern dynamics were emerging from my ad hoc queries. That led me to develop my top five geographic approach questions—a core set of questions that could only be answered spatially.

- What exists at a location?

- Where are certain conditions satisfied?

- What has changed in place over time?

- What spatial pattern(s) exist(ed)?

- Where do variables interact?

In academia, I encountered some unique and inspiring professors. The most influential ones in GIS were Dr. Sheila Lakshmi Steinberg and Dr. Steven Steinberg. Both were university professors who were starting a new course based on a book they co-authored, GIS for the Social Sciences.

I was in! I loved the idea of using a spatial intelligence platform to provide information in a logical system. I did not know what GIS was then, nor did I know it would change my life forever.

The Case for Participatory GIS

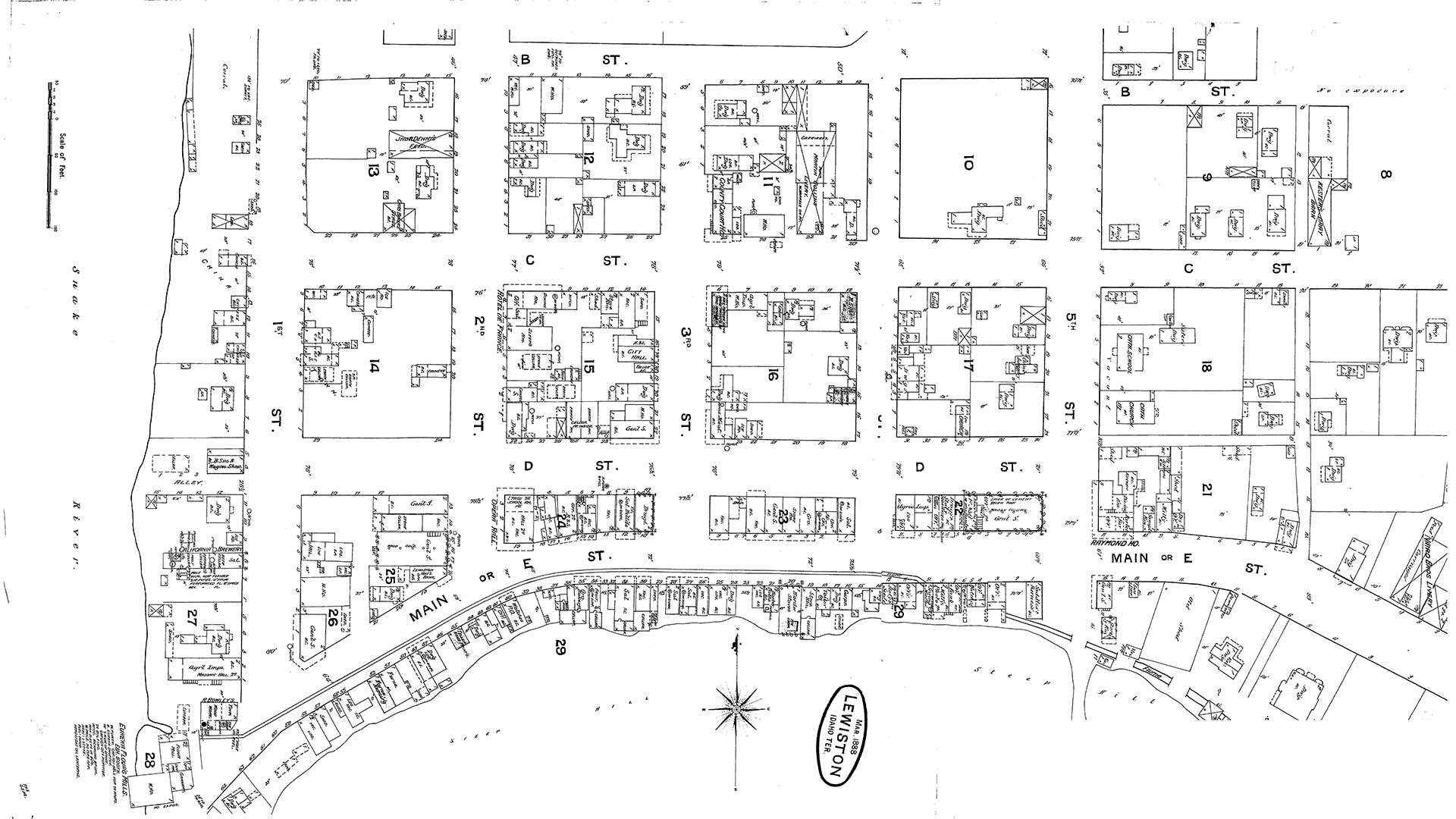

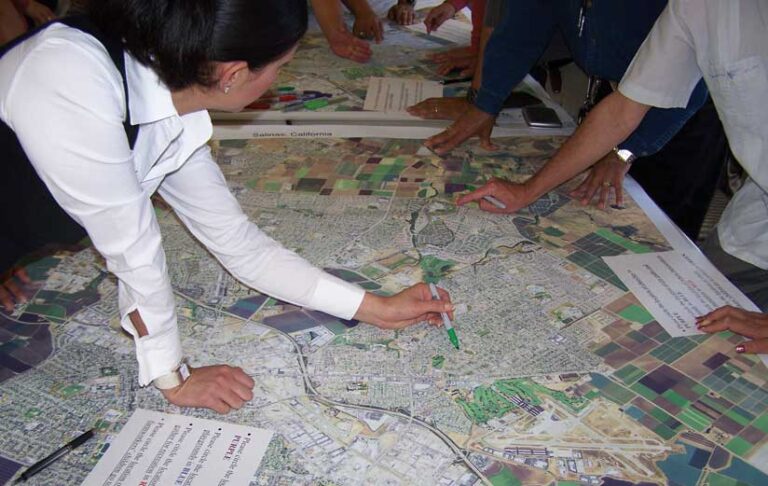

This one GIS course, along with my love of research and data exploration, allowed me to get my first paid student job on a GIS participatory research team for the Agricultural Workers Health Initiative (AWHI). [AWHI was an intervention funded by the California Endowment to empower agricultural workers to improve overall health in the community.] I examined pesticide drift in agricultural worker communities across the state and collected pictures and measurements and helped lead the qualitative portion of the participatory GIS mapping. I developed key informant questions, went into homes, and led focus groups. I asked questions about pesticide exposure and home decontamination procedures. I was able to work side by side with some excellent cartographers.

My team traveled throughout the agricultural lands of California, gathering stories of pesticide exposure in migrant communities. This work was an immediate success and led to publications and presentations to inform decision-makers of opportunities for real change and provided a precedent for using GIS to tell a community story and improve lives.

A few years later, I entered graduate school and continued as a research assistant, still exploring my top five spatial questions as applied to the ologies. I was the only person in the public health program with any experience in GIS. Yes, I still had only taken one class, but what I learned in that class—coupled with applied expertise and how to use location intelligence to communicate toward effective change—was still very applicable.

Making Effective Change with GIS

Dr. Lisa Pawloski, department chair in the Department of Global and Community Health at George Mason University, asked me to create a map of food deserts in Washington, DC, for a peer-reviewed paper. With my participatory GIS background and statistical knowledge, I could quickly link data and ground truth findings to ensure the story was accurate. We found that while many areas had grocery stores, those grocery stores carried no fresh food and had only processed or junk food. Understanding a community and its data are paramount for telling an accurate visual story. This is our responsibility as researchers and mapmakers.

The analysis I performed informed the paper, “The spatial food environment of the DC metropolitan area: Clustering, co-location, and categorical differentiation” by Timothy F. Leslie, Cara L. Frankenfeld, and Matthew A. Makara. Published in Applied Geography, Volume 35, Issues 1–2, this article is still used in literature reviews as a precedent for mapping food insecurities and telling the story of the food deserts in urban areas.

My previous experience in GIS—although minimal—left an impression and led to a paid graduate practicum experience in the Division of Maternal and Child Health of the Kentucky Department of Public Health. This work included environmental health. I was the only applicant with any GIS experience. Although it had been some time since I had used GIS, I got the gig. (This is a reminder to brush up on those GIS skills.)

The project focused on determining if there were any correlating geographic factors between children in Kentucky who were hospitalized for asthma and children who tested positive for lead poisoning. Using my top geographic approach questions, I explored the story behind the data. This was no easy task because no single variable could easily correlate both datasets. I was intrigued by this conundrum.

Of course, the solution was a spatial one—rural-urban classification codes. This project told a powerful story that led state officials to pass housing ordinances targeting areas with the most significant exposures. This experience let me learn on the job and make positive changes. I also received a job offer before my graduation.

What I have learned—and applied throughout my career—is that place matters. My first job out of grad school was as a contract employee for two initiatives—Health Happens for All and Health Happens Here—that were being run by The California Endowment (THE), a private nonprofit statewide foundation dedicated to making California a healthier place. I primarily worked under the prevention component of both Health Happens initiatives, although I touched all portions of Building Health Communities (BHC), another THE initiative.

Quality of life and life expectancy can be influenced by where you live, so ZIP codes helped focus these programs on areas that were most in need. These initiatives employed ZIP codes to target preventive programmatic efforts across California and developed innovative approaches to address the social determinants of health and promote racial and health equity. Along the way, these programs reimagined the role of philanthropy in public health through the creation of a new model for effectively supporting communities.

I was interested in examining policy, systems, and environmental change to enhance disease prevention and continued working in the health field and creating change through tribal health initiatives. I worked on the Good Health and Wellness in Indian Country initiative, a cooperative agreement with the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and tribal epidemiology centers and a few tribal nations. As an example, one of my projects supported sustainable farming practices at some reservations.

Using spatial thinking, I have brought my skills and knowledge of GIS to all my work as an advocate for this amazing technology and helped open the doors for folks to ask questions that can only be answered through a geographic approach. Every academic and professional path I have explored over a few decades has included some perspective of a geographic approach. Geography is everywhere. A picture is worth a thousand words, and a map is worth a thousand pictures. Keep asking questions and use those maps to tell the data story.