At the 2020 Esri User Conference, the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University won the Making a Difference Award for creating the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard.

Ensheng Dong, a doctoral student from Johns Hopkins University, created the iconic dashboard visualization the world uses to gauge the spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Less than a month into 2020, Dong heard that a new viral contagion, COVID-19, had begun to spread in Wuhan, the capital of China’s Hubei Province. Dong, a student living in Baltimore, Maryland, was thousands of miles away from the outbreak’s epicenter, but he had studied epidemics and knew how fast they can spread.

Taiyuan, the capital of Shanxi Province, has more than four million inhabitants and it is Dong’s hometown. Although it is 600 miles from Wuhan—the same distance that separates New York City and Detroit—Dong felt concerned for his family’s safety.

On January 20, the first case of COVID-19 in the United States was confirmed in Washington State. Suddenly, the virus—for Dong—seemed that much closer.

The following day, Dong met with his faculty adviser, Dr. Lauren Gardner, an engineering professor and the codirector of the Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering. They discussed the emerging epidemic and decided it was worth a closer look. Gardner suggested that Dong use GIS to construct an online dashboard to monitor unfolding events because he has a strong GIS background.

After completing his undergraduate work in China, Dong earned a master’s degree in geography and statistics at the University of Idaho. While interning at the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, he helped the agency use GIS to collect health-related data.

When Dong first contacted Gardner about the possibility of pursuing a PhD at Johns Hopkins, she was particularly intrigued by his facility with GIS, a skill Dong had honed during an internship at Esri. He arrived on campus at Johns Hopkins a few months before his program was to start, to assist in a study Gardner was coauthoring on measles vulnerability in the US.

“I immediately jumped into the project and helped her visualize measles risk in a dashboard,” he said. Media outlets, including the New York Times and CNN, featured Dong’s handiwork, a prelude to work that would soon focus on a much larger health crisis.

At Johns Hopkins, Dong studies systems engineering, which is a modernized approach to civil engineering for the complex, interconnected world.

“The emphasis is on civilization engineering,” Dong said. “It’s basically about the interaction of people with the built environment.” For Dong, the discipline allows him to explore ways to combine the objectivity of numeric data with the subjectivity of data visualization.

The Data Problem

Dong knew ArcGIS Dashboards was an ideal way to display data about the pandemic and provide a geographic visualization of the outbreak. A dashboard is typically oriented around a map, with accompanying charts, graphs, or other visuals to contextualize map imagery.

But a dashboard requires data. Soon after his meeting with Gardner, Dong gathered the data he needed to launch the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard. For the rest of January, he worked mostly by himself, driven by a desire to map the outbreak on Taiyuan, his home city.

“Ensheng and I were basically the two that started the dashboard, but he was really the mastermind behind it,” Gardner said in an interview for an Esri podcast about the dashboard. “He’s a total whiz with Esri technology and dashboard development.”

As cases began to multiply around the world, Dong struggled to keep up. He scoured the internet for reliable data, often consulting BNO News, a Dutch website that publishes COVID-19 data from several nations in tabular format. In addition to gathering data, Dong had to synchronize it, accounting for the different methods governments used for classifying cases as confirmed or recovering.

Twice a day, he would update the dashboard. “For a month, I barely slept—five hours a day or less,” he said.

One reason the work was so labor-intensive was that Dong was inputting all the data manually. A team of volunteers was assembled from Johns Hopkins to help update and maintain the site. In February, Esri’s Living Atlas of the World team helped Dong and his team with data scraping, automating the process of importing the data.

Cartography Communicates

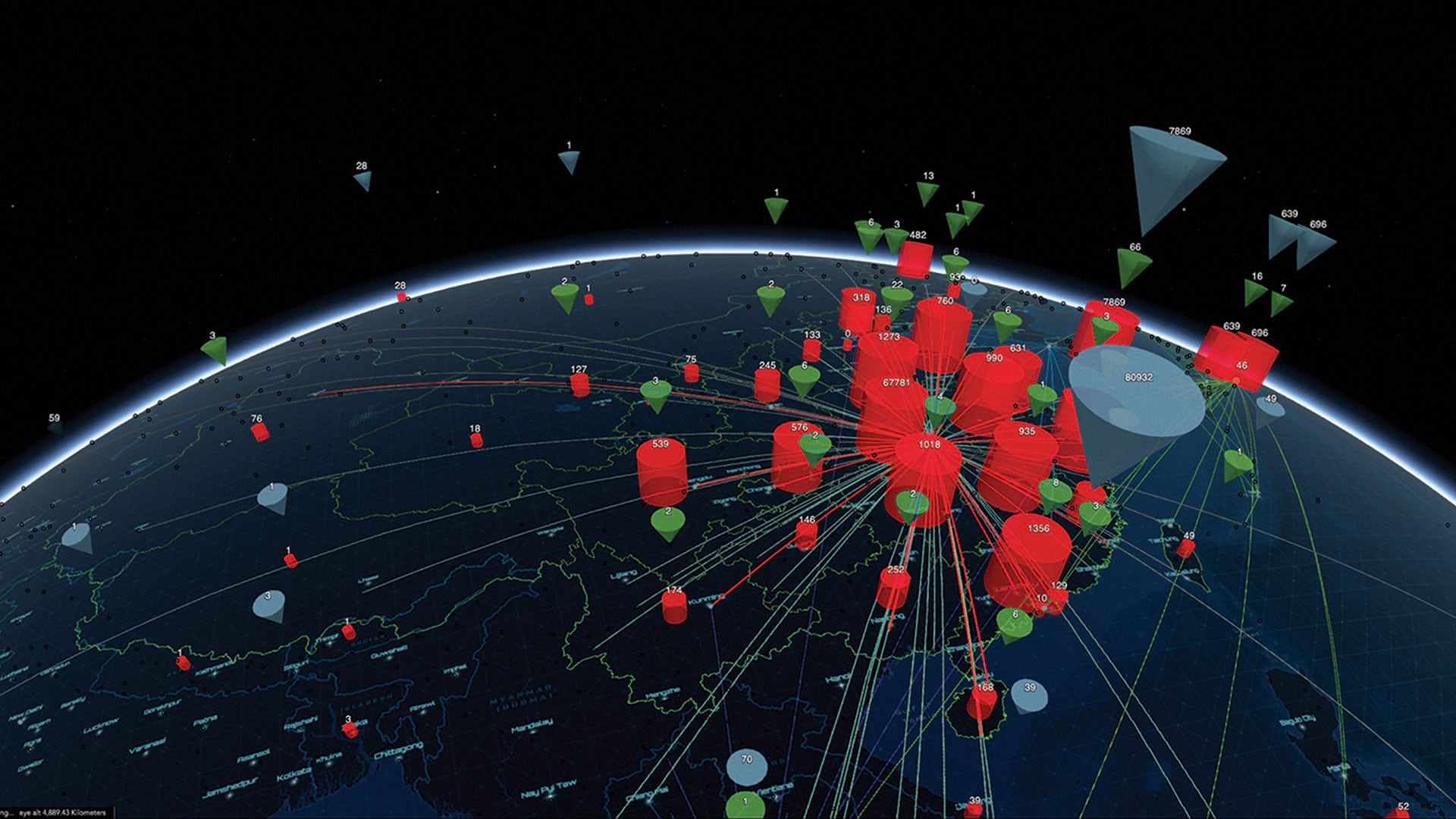

Soon after Dong began to amass data, he had to confront questions about how to present it. To emphasize the alarming nature of the pandemic, Dong chose to display bright red dots over a stark, black background. The larger the dot, the greater the number of COVID-19 cases in that region.

But behind each red dot lurks a plethora of choices. A major decision involved how to break down the data for presentation.

As Dong’s team adapted the map to provide worldwide data by state and province—and, in some countries, such as the United States, by county—these choices multiplied. The county-level perspective means the United States is blanketed in red dots, while other countries may have one large red dot and a lot of blank space.

“As we get down to the state level, for large countries like Russia, we can spread out that one large dot, so you’ll see more distributed dots that aren’t as large,” Dong said. “That’s a tricky thing for geographers—what’s the best size for the dot?”

A map like this needs to inform and empower people to take action, but it also runs the danger of making people lose hope so that they see no way out of the crisis.

“We’re constantly adjusting the dot,” Dong said. “We added a few other maps besides the cumulative and confirmed cases, such as active cases, to clearly communicate the data we were collecting and sharing. If more people in your country are recovering, you refer to that map. The dots are smaller, and you feel better.”

Directing Increasing Traffic

Increases in dashboard visitor traffic indicated the disease’s progress. “We had at least three crashes,” he said. “Each time, it was because of a surge of cases in new locations. I remember that at the end of February, as Italy and other European countries had more cases, we could see that a lot of Italians were jumping on the site to see what was going on.”

By mid-March, around the time the World Health Organization officially classified COVID-19 as a pandemic, Dong’s team was able to automate updates from all US counties.

As the world took notice, Dong and his team were driven to provide up-to-date and authoritative data. What began as an attempt to monitor the outbreak in China has evolved into one of the world’s most trusted sources of information on the pandemic.

“I think we’re now getting somewhere between 3 and 4.5 billion requests a day,” Gardner said. “And they’re coming from everywhere. Most of it is just individuals clicking around on the dashboard, but there are definitely lots of requests for the data that we make available, which other groups are pulling data directly into their own internal dashboards and using for policy making.”

With the data gathering mostly automated, Dong can step back a bit from the site and begin to study the epidemic itself, using mobility models as the basis for his doctoral dissertation. But with his adopted country now the pandemic epicenter, he still keeps an eye on the map.

“Initially, dots were mainly located in China and East Asia, and I worried about my family,” he said. “Right now, my hometown has zero new cases, but today there is a large dot near where I live in the US.”

The Data Tells Stories

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread around the world, the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard expanded its scope. What began as a modest effort by graduate student Dong to map the disease in China has become a multilayered resource that includes supplementary graphics and expert analyses.

With the epicenter now firmly established in the United States, the most significant addition to the Johns Hopkins Dashboard is an embedded United States map.

This part of the project was the brainchild of Beth Blauer, the executive director of the Centers for Civic Impact, a Johns Hopkins organization that works with local governments to use data to address problems. Blauer was one of the key architects of CitiStat, a program launched by Martin O’Malley during his tenure as Baltimore’s mayor to gather data as part of a smarter government approach. Blauer also ran a similar statewide program after O’Malley was elected governor of Maryland.

When Dong first launched the dashboard, COVID-19 was the story. Blauer recognized that as the pandemic touched the lives of millions of people, there was a story within the story. Actually, there were many stories especially in a country like the United States, which has stark extremes of socioeconomic inequality. Data associated with the pandemic could reveal the uneven nature of its impact.

The US map, which went live in April, displays county data relating to hospital capacity; health insurance availability; and demographic breakdowns, including statistics relating to age, ethnicity, and unemployment. The map, which also includes comparisons with statewide data, has proved to be a powerful illustrator of the inequities associated with COVID-19 and the disproportionate vulnerability of communities of color.

The overall effect of the US map is a reminder that behind all those red dots are lives in peril. In an interview quoted in the Washington Post, Gardner said, “When you actually start looking at the affected populations, it becomes so much more human.”