Every university must contend with the daily flow of people commuting to and moving around the campus. How can the students, staff, and faculty of a large university be encouraged to commute safely using alternative and sustainable transportation methods instead of individual cars?

GIS and spatial data can provide campus transportation planners and administrators with a view of the campus community’s behavior patterns and transportation dynamics that can help inform decisions.

A long-term and mutually beneficial relationship at Colorado State University (CSU) between Parking and Transportation Services (PTS) and a campus geospatial resource called Geospatial Centroid (the Centroid) has not only improved how the campus functions but also benefited a talented and motivated team of student interns.

Cross-Campus Connections

From his first week on the job in 2013 as the alternative transportation manager at PTS, Aaron Fodge knew he needed the power of GIS to do his work effectively. His role was to expand the options for efficient, convenient, and reliable commuting and communicate how and why the entire campus community could benefit from using other transportation options. To do this, he needed data—specifically, spatial data—and a way to visualize it. Around the same time, the Centroid was established at the Morgan Library at CSU. Fodge, who lacked the necessary GIS capabilities within his own team, immediately tapped the Centroid for help.

Putting Students to Work

As Fodge began this formidable task, the Centroid was grappling with how to ensure it could satisfy the needs of its clients despite having no significant funding to hire professional GIS staff.

Enter the student interns.

The Centroid already welcomed students from across campus to assist in performing small GIS and mapping tasks that complemented their classroom learning and furthered their hands-on GIS experience. However, the work Fodge needed would be substantively different. It would require developing new methodologies, new data management systems, and a vision for long-term maintenance.

These initial efforts in recruiting interns laid the groundwork for a long-term, comprehensive spatial database and delivery system that would significantly influence transportation planning as well as student learning and development.

Building on a Foundation

An initial scope of work outlined tasks the Centroid would perform for PTS. These tasks included gathering data from existing sources and developing maps to show a snapshot of the CSU community and its commuting options. Fodge found that sharing even the most preliminary maps with his colleagues and partners, helped them see the city differently.

Since these initial activities, the annual scope of work between PTS and the Centroid has been revised and expanded. These activities have built on previous achievements, while looking ahead and utilizing advances in technologies and the increasingly sophisticated skills of Centroid interns.

In addition, data providers from across campus—from the student records office to the police department—have realized the importance of generating accurate and clean spatial data. These providers have improved and streamlined their methods for recording and sharing data with the Centroid.

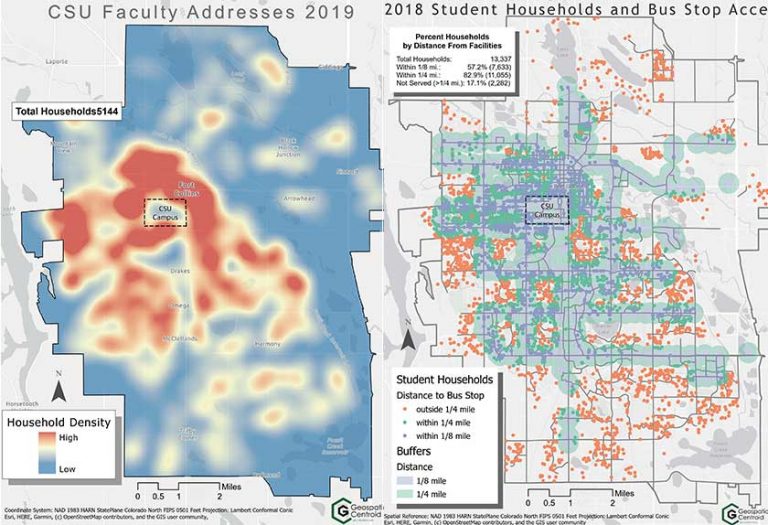

Where Do Commuters Live?

The first question was to find out where commuters to CSU originated. Each year, CSU collects the addresses of its students, staff, and faculty. This seemingly straightforward geocoding task was confounded by the fact that address fields did not clarify the difference between a local address and a home address. Consequently, some students’ home addresses were located beyond a reasonable commuting distance—sometimes outside the state or country.

For the purposes of creating a reasonable commuting reach, the points for home addresses were restricted to a 50-mile buffer from campus or a three-county region. As with other aspects of this project, educating others about the importance of spatial data—gathering it and making it usable—has also evolved. Now the survey for incoming students explicitly asks, “What is your local address while attending CSU?”

Knowing where people commute from enables additional analyses. If this data is consistently collected and mapped over time, observations can be made with respect to where people choose to live and whether patterns emerge when new transportation options are introduced.

All CSU affiliates can ride buses for free. After the introduction of the MAX, the new north–south bus rapid transit (BRT) line in Fort Collins, there was evidence that some CSU affiliates moved closer to the MAX corridor. Similarly, a buffer analysis around bus stops and routes quantified what percentage of CSU affiliates were being adequately served by these routes and where there were gaps.

Buses, Buffers, and Boardings

Transfort is the transit service in the city of Fort Collins. Because CSU is the largest employer in the city, Transfort is very receptive to the needs of the CSU community. Transfort has been an excellent partner for both PTS and the Centroid and has willingly shared its data. Every year, it provides new bus route shapefiles so that analyses can be kept current and accurate. Every month, Transfort shares bus boarding data, which includes the time, route number, and GPS point location for every CSU affiliate who uses a university ID card to board the bus.

Transfort boarding data is further processed to convert the GPS-generated coordinates into a spatial context and associate the imprecise boarding locations with specific bus stops. Erick Kelly, the first Centroid intern to work on the PTS project, developed protocols that generated buffers around each bus stop so that the number of boardings per bus stop could be calculated. This analysis revealed which stops were heavily used and which were not.

Kelly’s efforts provided the basis for building more efficient and accurate methods to show CSU bus ridership across the city. His maps clearly showed gaps where neighborhoods were not being served. Fodge now had concrete evidence so that he could work with Transfort to modify its bus routes to better accommodate CSU commuters. This work helped secure a $1.5-million study to design a second BRT corridor in Fort Collins.

Bikes and More Bikes

Fort Collins and CSU are recognized as being exceptionally bike-friendly places. Bikes are a significant part of the culture. CSU was named a Platinum Bicycle Friendly University by the League of American Bicyclists. The city’s annual Tour de Fat bike parade attracts thousands of zany revelers.

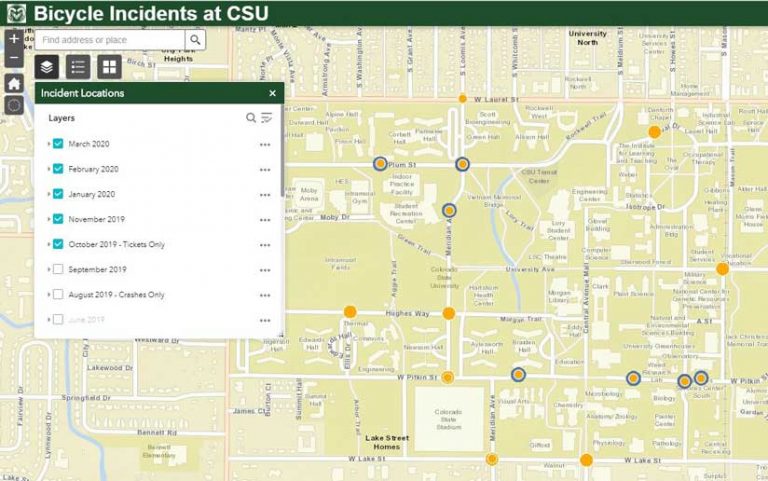

However, not all riders ride safely or courteously, particularly on campus. Can data help? By mapping the data, powerful stories can be told. The Centroid’s bicycle-related work focuses on plotting the location of tickets and crashes. While the CSU Police Department (CSUPD) records all bicycle incidents, including tickets and crashes, documenting the specific location was historically not a priority. When an officer recorded the location of an incident, it was as a verbal description, such as “south of Lory Student Center” or “on the corner of Plum and Meridian.”

By geolocating bicycle incidents and using graduated symbols to display them on a campus map, it became obvious where problems were. PTS could channel resources specifically to these places, adding increased signage, and even providing bike traffic monitors to encourage enforcement of safe policies.

Erica Cirigliano, a nontraditional student with extensive programming skills, volunteered to create a script that could translate these verbal descriptions into consistent point locations. Instead of manually locating bicycle tickets and crashes, this script would be used by interns to automate the process of accurately locating bike incidents.

However, within a few years and with some gentle pressure from the Centroid, CSUPD became cognizant of the extreme value of location information for detecting trouble spots and evolved its data collection methods. Now CSUPD provides data with latitude-longitude points, which has significantly improved accuracy and efficiency.

Online Delivery

After the first few years of data collection and map creation, it became clear that this information needed to be more accessible and widely shared. Every month Fodge meets with other transportation planners in the City of Fort Collins. Having access to these maps and data would enrich the discussions at these meetings and ensure that decisions are based on evidence.

The improvements and accessibility of ArcGIS Online, along with CSU’s campus-wide site license, made it the obvious choice. Danielle Davis, a recent geography/GIS graduate from Michigan State University with experience in the transportation sector, coincidently and fortuitously found her way to the Centroid office at just that time. She has since become a graduate student at CSU.

Over the next year, Davis built several web applications that not only visualized existing bicycle and Transfort data, but also allowed for ongoing updates. With these apps, Fodge could see data in near real time, visualize change over time, and readily share data with other transportation planners.

Retroactive Data Management and More Efficient Processes

After five years, despite a relatively well-functioning system in place, there were data organization and management issues that needed to be addressed. File management and naming conventions were not always as tidy as they should be. That led to inconsistencies and caused frustration when access to historic files was necessary.

Fortunately, Joshua Reyling, a new Centroid intern, could clearly see the issues and set about to clean things up. From ensuring that projections were consistent to automating naming conventions, Reyling worked tirelessly to bring order to the chaos. He created topical geodatabases (e.g., Bicycle Tickets, Bicycle Crashes) with feature datasets for each academic year. These geodatabases contained monthly data processes and outputs. The data is now clearly named, accessible, and easy to find.

In addition, Reyling streamlined and improved the methods for processing the Transfort boarding data by creating a Python script to perform tasks that previously had been accomplished manually. Instead of creating buffers around bus stops and counting the points that intersect, his script relied on referencing Thiessen polygons created between the stops, and then performing a spatial join to associate each boarding with its respective stop. This has increased efficiency and reduced user error.

Like many relationships, there are times of relative calm followed by times of significant change. In a small way, the past seven years have followed this pattern. New systems are created in a disruptive push, which are followed by a period of calm, until a change is needed.

In this case, much depended on the individuals present and the technologies available. Kelly used existing tools to build the initial foundation and Cirigliano increased efficiency while expanding her programming skills. Davis learned to publish services and develop web mapping applications and Reyling learned to write code to wrangle data. Each of these interns contributed their unique skills, influenced the improvement of the local transportation systems, and enriched their own careers at the same time.

Fodge understands and appreciates a geospatial approach. From the start, his instinct was right—he needed spatial data and a competent GIS team to accomplish his mission. He regularly sings the praises of the Centroid and the intern program that enriches student skills while providing him with exactly the kind of evidence he needs. He is often the envy of his colleagues at other institutions who ask themselves Why don’t we have a Geospatial Centroid?

For additional information, contact Sophia Linn at Sophia.Linn@colostate.edu or visit the Geospatial Centroid website.