One month after George Floyd was killed while in police custody in Minneapolis, Minnesota, street artists in Atlanta, Georgia, painted an unsanctioned Black Lives Matter mural on the east side of the BeltLine, a popular walking trail created on the bed of a former railroad line.

As of press time, the artwork remains untouched, as it is seen as a catalyst for conversations on race. Yet this mural runs alongside the Old Fourth Ward and Eastside, among Atlanta’s most historic—and historically Black—areas, which are now the site of rapid gentrification.

Just a few feet from this powerful work of public art, thousands of Black individuals and families were and are being displaced by revitalization efforts whose looming condos and new amenities will create pristine, planned communities in the heart of Atlanta—communities that will be mostly affluent and predominantly white.

Whose lives ultimately matter on Atlanta’s east side?

Present-Day Colonialism

As professionals who address spatial dynamics through geography, GIS, planning, and more, we like to believe that colonialism and imperialism took place long ago in distant lands. But we reproduce colonialism through research, policies, and teaching—and we need to recognize that. By colonialism, I mean not only the practices of dominating and replacing existing populations in spaces and places but also the mental patterns and elements of professional training that lead us to accept, normalize, and promote those practices.

Certainly, we often also use analysis to critically interrogate the world we live in. Yet our data and numbers can themselves prevent us from interrogating our own blind spots. We use quantitative, and sometimes qualitative, research to justify our claims regarding space while ignoring what occurs—who does what to whom—in that space.

Who constitutes the “we” of our profession also matters. Without robust racial representation, we cannot have a geospatial workforce that is experienced and prepared enough to engage with the critical questions of cities, towns, and rural communities. (See “Earth Science Has a Whiteness Problem” for more on this.)

I challenge us to consider the impacts of our work on the everyday spatialization of public space. How has data science, as a tool, impacted not only the future of cities but also the current battles over racial violence and racial injustice?

Communities Have Realities

Four years ago, while living in Atlanta, I occasionally attended city hall and planning commission meetings to remain connected to conversations surrounding urban design, development, and policy. I once sat in a room of planners and graduate students who were discussing the future of Atlanta. Even though the theme of the conversation was What Is Your Atlanta, the Atlanta in that room was not representative of the city.

It was a predominantly white, well-heeled, elitist, and closed space. Participants in the group cited data and examples of crime prevention that rested on environmental design and the blending of public and private spaces. They completely ignored the role that race-based policies have played in shaping the city.

While this discussion was intended to cultivate entrepreneurial innovation around urbanization, the nearly uniform social, political, and economic standing of those in the room ignored the history and lives of the people who are impacted by their policies. Furthermore, the event was advertised among networks of acquaintances and occurred at a time and place that fostered an inequitable and exclusionary decision-making process. As a result, the gatekeepers and power brokers engineered communities that they visualized more as properties on a Monopoly board than as real people.

In addition, experts, armed with long-range data that insulates them from immediate consequences, often ignore economic realities. Take, for example, the well-known scholar who spoke at Atlanta’s planning commission about the development impacts of the BeltLine. He had recently accepted a joint position in real estate and urban planning at the university where he taught, and I was struck by the convergence of commerce and planning in academia contained in that title.

As I scanned the audience that day, I noticed a repeat of the previous meeting: I was surrounded by the same people, just in a larger venue. After the professor’s lengthy talk and bold predictions, we entered the Q&A period, where local residents posed questions about rising housing costs, gentrification, and the unsustainable population bubble that choked Atlanta. I recall one interaction most vividly: a white, middle-aged man described the extreme gentrification that was occurring in the neighborhood he grew up in, Cabbagetown. He stated that it was becoming difficult to afford his mortgage and property taxes.

The professor dismissed this man’s concerns. Eventually people would grow tired of the city, he insisted, and the cost of homes would decline. The professor’s reliance on a long-term scenario—so popular in planning practice and so prized in data analysis—failed to even consider what would happen to people in the meantime.

As so-called public forums, these meetings illustrate the extent to which a powerful few make decisions behind closed doors. This power frequently goes unseen and unchecked.

Race-Conscious Geospatial Practice

When geographers and planners of color hold the opportunity to frame and use the powerful, exploratory tools of geoscience, outstanding work is possible—work that creates a path for responsible and effective decision-making in matters of community planning, public health, economic development, business creation, housing and homeownership, and much more. Once we commit ourselves to a more diverse and representative geospatial practice, we will be committing to a future of thriving, healthy, equitable neighborhoods, towns, and cities.

Just one example of the depth and dimension of data frameworks that are made possible by racially just geospatial practice is the Texas Freedom Colonies Project. In mapping the presence of more than 550 (and counting) historic Black settlements in Texas, Dr. Andrea Roberts’s participatory atlas reflects the full history and status of these places. Using ArcGIS technology, residents and descendants of these communities can submit qualitative and quantitative evidence of settlement, from deeds and documents to personal recollections and family trees. So far, Roberts, an assistant professor at Texas A&M University, has verified and mapped 357 communities and made place-names and crowd-sourced information available for 200 more.

The processes for confirming and documenting these irreplaceable places are an act of community revitalization and preservation. Mapping these once-rural communities—many of which are in the path of exurban development and have been subjected to devastating environmental pollution—improves their chance for survival. The Texas Freedom Colonies Atlas includes layers for the state’s current transportation projects, 2010 Census data, and Hurricane Harvey disaster areas, making it a critical resource for addressing current planning problems as well. (Read more about Roberts’s work.)

Transforming Our Profession

Recently, as I have watched the news and lamented my own position as a Black woman, planner, and geographer, I’ve been paralyzed by intellectual fatigue.

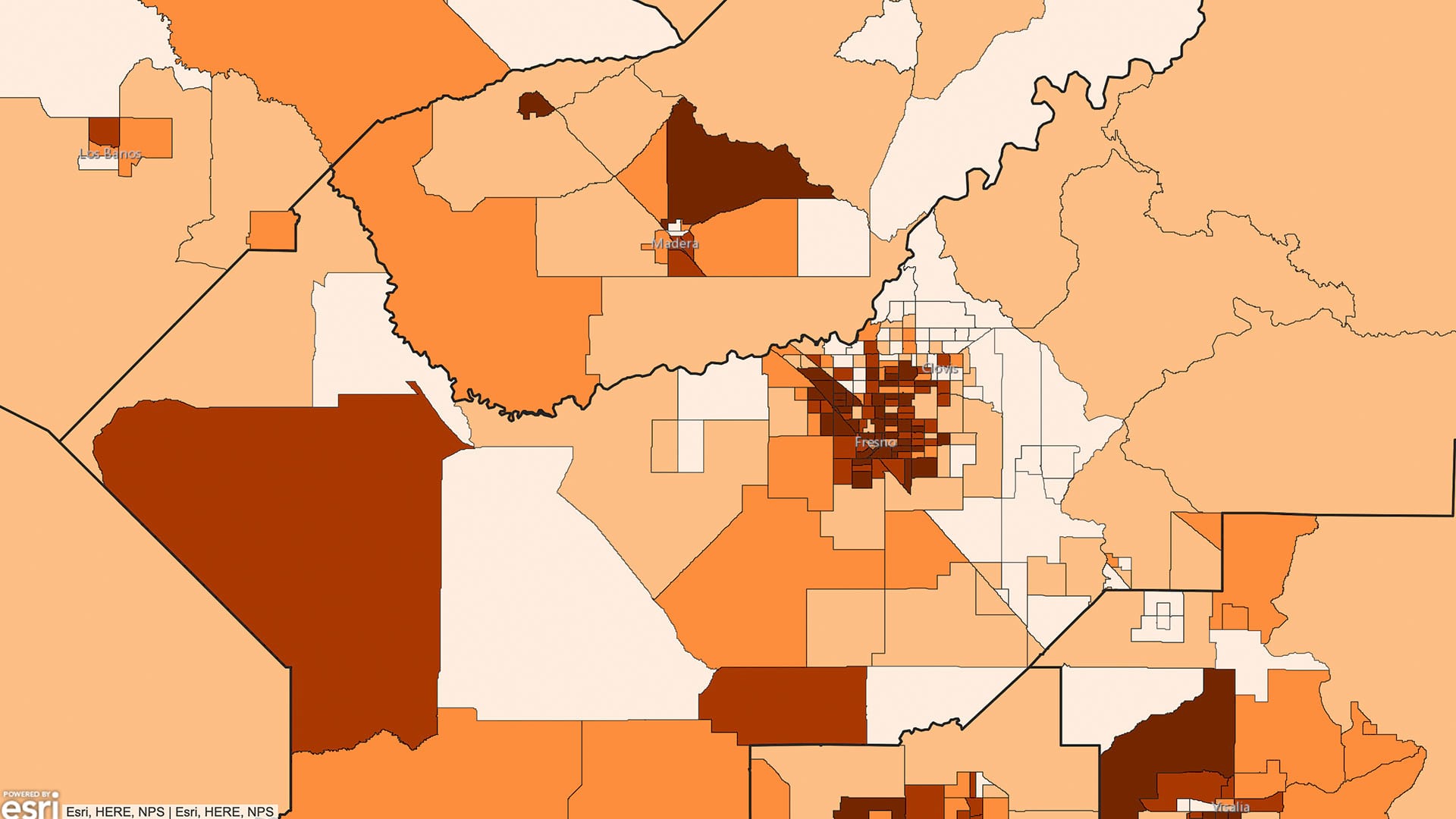

With the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, we can no longer pretend that everything is business as usual. Our cities today are an amalgamation of not only redlining, historic zoning codes, and Federal Housing Administration (FHA) policies but also of color-blind data science that is used to justify the demolition of communities of color.

As I look at images of the BeltLine in Atlanta, I am reminded of the decisions made by faceless planners who mapped boundaries that excluded and displaced people—people whose lives didn’t matter to those planners. We must transform our profession’s practices in ways that incorporate community-based participatory action, research, qualitative data, and socially conscious policies while bursting the pipelines that skew our field white and male.

Our communities are more than dots and lines. They are people and places.