National GIS Is for People’s Empowerment and Better Governance

National GIS of India is an innovative program within the country’s Twelfth Five Year Plan that has generated much interest. Spearheading many of its component efforts is Dr. Mukund Rao, member-secretary of the National GIS Interim Core Group and chairman of the GIS Task Force of the Karnataka Knowledge Commission. Rao has more than 32 years of experience in earth observation (EO) and GIS programs and building space activities. His unique experience—working in both government and the private sector and now in the consulting domain—brings impactful and effective practices. Over the years, he has also provided leadership to many national and international forums related to EO, GIS, and space. Recently, ArcNews had an opportunity to speak with Rao.

AN: What is National GIS?

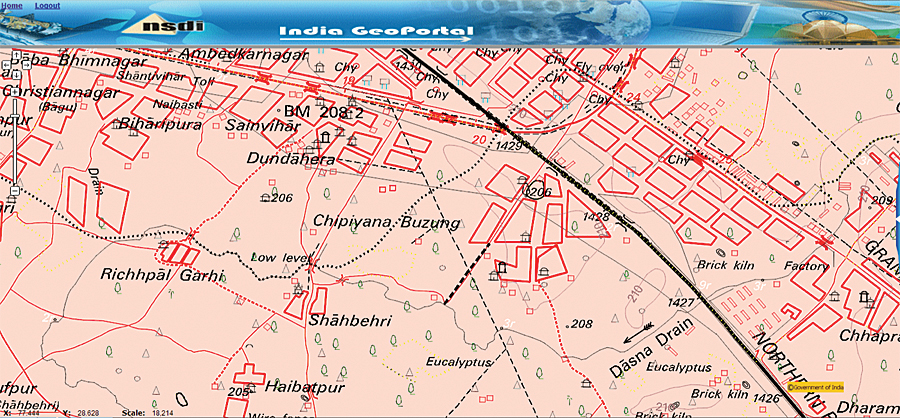

Rao: National GIS is India’s next-generation GIS program, envisioned as critical support to the national governance and empowering its citizens—thereby extending GIS to all levels of society. In the long term, National GIS is envisioned to build national capability in GI and enable India to maintain global leadership in GI. India has vast experience in mapping and GIS—systematic mapping has been carried out for more than 200 years; remote-sensing images have been used for the past 40 years, and GIS technology has been used for almost 30 years. India has realized that the true power of GIS can only be realized when GIS is embedded within governance and taken to every citizen.

AN: What is the significance of National GIS now?

Rao: First, as a nation, we are witnessing tremendous progress, and our economy will grow significantly in the coming 5 to 10 years. With such growth, society will demand very high efficiency in governance and quality services, and the government will depend on very efficient, guaranteed methods of nation building and bringing equity in quality of life for people—doing so with transparency, speed, and compassion. Immense amounts of analytics will be called for. Support data/information systems have to be ready to use and no longer limited by the need to start getting organized. As demand on governance is becoming anticipative and futuristic, the decision process must always be a step ahead of the people’s demand. Similarly, democracy demands inclusiveness, and thus citizens must be able to participate in and judge every development option/decision or even demand specific development needs—this, too, National GIS should be able to provide. Thus, National GIS will not only improve the efficiency of governance but also enable citizens to participate in the development process.

AN: How is this different from GIS in India today?

Rao: I think the key differentiator is the shift from a data generators drive to a user demand or national needs drive. Meeting what the user needs (or what the nation wants) is the supreme goal rather than providing only what is available—most times, data generators seem to be driven by what technology can offer or make available, whereas user needs require ready-to-use authoritative GIS data; therefore, a wide gap emerges between these two ends. Thus, even though the nation has a long history of surveying and mapping, years of imaging, and many years of GIS project activities, the usage of images/maps/GIS has yet to be impactful and meaningful to grassroots levels. Until such GIS-ready and user-specific data for the whole nation is easily available, how can a user or governance mechanism or citizen make the best use of GIS technology in decision making, and how can citizens be really empowered? National GIS would bridge this wide gap and ensure that GIS-ready data that is regularly updated as users require is made available.

Another differentiator is in the shift toward a mandated, organizational structure for National GIS and the shift away from just doing GIS projects—thereby critically aligning the existing multifarious remote-sensing and GIS activities to this national goal. Over the past 20–30 years, many GIS projects have been carried out by quite a few organizations—thus, while projects have been completed, these are contributing less to effective and efficient use in decision making and becoming part and parcel of good governance. We have realized that simply doing GIS projects is not leading us to this goal, and we need an organizational mandate at the national level—that way, GIS will get the responsibility and also bring accountability. To this important shift, the visualization of the Indian National GIS Organization is something critical, important, and unique.

AN: What are the challenges for National GIS?

Rao: The biggest challenge is already behind us; that is, getting the concept debated/discussed and endorsed. This has happened very efficiently, thanks to the Planning Commission’s efforts. Almost all ministries (in central and states), GIS industries, GIS academia, etc., have been consulted, and a wide range of discussions have taken place. This first round of consultations led to the vision document for National GIS (in October 2011). Even after the vision document was prepared, the Indian government has undertaken another round of in-depth consultation for programmatic and financial approvals. Now, National GIS has been marked down as a new initiative in the Twelfth Five Year Plan. As I gather, the last round of processing is in its final stage of approval by the Indian Cabinet. So, I think, now the issue is not what National GIS is or whether National GIS is required but when National GIS will become operational.

Workwise, there are many challenges, but none of these are insurmountable. Technically, one challenge is organizing the National GIS asset that is seamless, nationwide, and GIS ready. Getting almost 41 parameters of data organized into a national spatial frame is a challenge—India still does not have an authoritative spatial foundation framework, and this will have to be organized for the first time. Similarly, bringing in myriad sets of available survey data, maps, images, tabular development data with geotagging, cadastral data, etc., is also going to be a challenge—a voluminous challenge! Designing and developing a data updating cycle and creating a GIS warehouse for timeline GIS assets will also be important. Even as the GIS asset is organized for the first time, the importance of updating existing content, adding more content, and keeping the GIS asset live and updated will become a prime goal.

At the same time, creating an environment for the widest usage of GIS applications is yet another challenge—especially considering the wide variety of user ministry (at central and state levels) and citizen needs that will have to be met from a GIS perspective. Thus, a culture of National GIS apps has to be developed and positioned. Similarly, establishment of the GIS infrastructure and systems has to be undertaken.

There would be critical policy, access, and licensing issues that would have to be positioned. Already, some thought has been given to the GI policy (through a study undertaken by the National Institute of Advanced Studies), and tenets for a national GI policy have been worked out. Human resource development in states, central government, and citizens at large will also be important, and program elements for these have been defined in a report being prepared by the Ministry of Human Resources Development.

What will be also challenging (and proof of success) is to make all these elements work in tandem and establish an operational framework by which GIS data and GIS application services become a reality and for National GIS to be firmly embedded in the nation’s information and governance regime.

AN: What about policy needs? You have also been associated with the GI policy study.

Rao: National GIS will need innovative policy instruments that are quite different from those available today in the five individual policies. Policy has to be determined in an analytical manner—defining the long-term “GIS ecosystem” goals and short-term achievements. Such an overarching GI policy should not only operationalize National GIS (in the short term) but also enable national GI excellence, industry participation, academic emphasis on GIS, and the nation’s commitment to citizens for GIS. In a study undertaken in India, we have prepared a comprehensive, first-of-its-kind policy report that includes a draft of the national GI policy. The report has already been submitted to the government and is a major input for positioning National GIS.

AN: What about the Karnataka GIS?

Rao: When we completed the visioning of National GIS in October 2011, it was recognized that the success of National GIS will be exponential if states’ GIS needs are also met; after all, states are a more direct mechanism for delivering governance and are directly closer to citizens. So, thanks to the government of Karnataka, we took up a task force study to logically drill down National GIS to a state requirement study. We conducted state-level discussions and workshops and stakeholder/user meetings and determined that states’ needs would be much greater and quite different than what would be required in a national GIS. The GIS data needs comprise almost 60 parameters, and most of the GIS applications need to be linked to cadastres—that becomes very important at the state level.

What we also see happening is that if state GIS programs are organized, they not only achieve some key goals of National GIS but also trigger a set of GIS apps at the state level—thus, Karnataka GIS (and other state GIS programs) can become vehicles for quickly and systematically organizing an aligned GIS that not only serves state-level governance and citizen needs but also integrates well into National GIS. Many other states are also being primed to align their GIS tasks into the National GIS system. Now, with the vision of National GIS and the Karnataka GIS, we understand what it will mean to develop state systems and how the dovetailing to National GIS would happen. Now, we see a GIS system of systems—meeting state and central governments, citizen, and enterprise needs.

AN: What about schedule and budget and official sanctions?

Rao: National GIS is now part of India’s Twelfth Five Year Plan. The proposal is to deploy National GIS in two stages and complete the establishment process (with many GIS data and app services also rolled out) in about three to five years—after which the operations and maintenance phase would be undertaken. As I said earlier, all the groundwork is now done, including financial approvals, and it is just the last step of cabinet approval that must be accomplished. Within the state of Karnataka, the schedule for Karnataka GIS is about two years, and here, too, the state-level processing is in its final stage.

Budgetwise, I can only say that, as the government of India (and state governments) is determined to implement National GIS, budget would not be an issue—especially for such a well-developed program that has endorsement at all levels.

Like many in India, I am keenly looking forward to National GIS becoming one core element of the development process and for GIS to be firmly embedded in every governance process and for empowering every citizen of India.

For more information, contact Dr. Mukund Rao.