Wherever businesses come in contact with people, they are working hard to minimize hazards and ensure safety.

Spurred on by consumers who demand safe practices from the companies they support—and mindful of the consequences of negligence—pioneering organizations are pushing beyond what is necessary as they find new ways to safeguard the public.

Here we reveal how companies are using technology to see where the public is vulnerable, understand why, and develop strategies to lessen the chance of harm.

Quietly, their work is saving lives.

Seeing Clear to the Danger

For one electric utility in Australia, 2015 and 2016 were average—and dangerous—years. During that time, residents made 1,400 accidental contacts with the company’s assets: overhead power lines, underground cables, utility poles, and other structures.

Ostensibly, the offenders were civilians and working professionals driving cars, tree-trimmers, grain harvesters, and excavators. But the real culprit was lack of visibility. No one involved in the incidents set out to contact high-voltage equipment. They simply didn’t know where hazards were located before they broke ground on a housing project or maneuvered a tractor around a worksite.

The minor incidents resulted in damage to property. The high-impact events cost lives.

Concerned, managers and executives responded by investing heavily in the utility’s hazard prevention and education efforts.

To help prioritize their outreach to customers and the community, they set out to identify the types of incidents that occurred most often. For that, they needed visibility into the location of all incidents, the contributing circumstances, and the most grievous outcomes. The team enlisted a technology commonly used to map utility networks—a geographic information system (GIS).

GIS created location intelligence by plotting the 1,400 incidents on a map of the company’s service territory—all 300,000-plus square miles of it. For each incident, executives could see the vehicle that made contact with electrical equipment and the type of equipment involved, as well as when it occurred and whether injuries or death resulted. Among other revelations, the analysis showed a high concentration of accidents on farms during months that coincided with harvest seasons.

More Effective Education and Prevention

Knowing that farm vehicles—balers, forklifts, backhoes—frequently hit overhead wires revealed only part of the story. The utility company needed to peer deeper into the problem to see why. Executives turned to artificial intelligence.

On public roads, utility companies can pinpoint where low-hanging wires might cross paths with cars or trucks, and install warning equipment to minimize accidental strikes. But the roads on farms—even large ranches with miles of improvised roads—aren’t mapped in public databases. The utility team couldn’t see the conditions that created the company’s greatest hazard.

They turned to a GIS-based machine learning model to create the visibility they needed. The model paired coordinates of each incident with satellite imagery of the area, and began to spot unpaved farm roads that crossed beneath power lines. With that insight, the team could see what it hadn’t previously seen.

Armed with location intelligence, company representatives fanned out to talk to farmers about safety and install preventive equipment on power lines.

The utility’s GIS also helped staff schedule outreach for maximum effect. The system identified not just the location of farms, but what type of crops they grew. Using that data, the company timed its outreach to precede the various planting and harvesting seasons, when farmers and farm equipment would be most active.

The utility even gave farmers a GIS-based app that revealed electric infrastructure and hazards on their land. Similarly, crop-dusting pilots could access an app to visualize power lines at each farm where they applied treatments.

Through these efforts, the utility helped farmers see—and avoid—dangers that had previously been unseen.

Saving Lives on the Brink

Around the world, suicide attempts are a difficult fact of life on railways.

Germany reports an average of 800 suicides by train every year. In Japan, 6 percent of suicides happen on the rails. In the US, nearly 1,700 people ended their lives on train tracks in the six years leading up to December 2017.

In each instance, one life touches many others. The train conductor becomes an unwitting accessory to death. The victim’s family loses a loved one. Railroad police and first responders encounter a scene that can stay with them for years.

Amid the magnitude of the human tragedy, there are also operational consequences. Hundreds of passengers will be stranded on their journeys to work, weddings, or job interviews. Some may be injured due to the abrupt engagement of the train’s brakes.

Officials at Amtrak, the only high-speed intercity passenger railroad in the US, did not accept train suicides as inevitable. Instead, they have chosen to use data to change the story.

Early signs show it’s working.

Convincing the Skeptics

Barbara Petito didn’t think it would. The Amtrak Police Department’s lead communications specialist thought there wasn’t much that could stop someone bent on ending their life.

“I was not on board in the beginning because I just didn’t know that we could measure any value. And I was not sure that, honestly, this was going to be a method to eliminate the incidents of suicide on the railroad,” Petito told WhereNext.

But Amtrak chief of police Neil Trugman was convinced the company needed to take action, and a colleague named Michelle Jennings had already begun using data and location intelligence to assess the situation.

When Petito got involved, she found Jennings hard at work, using GIS technology to spot unseen patterns in the data.

Grim Trends Emerge

With approximately 87,000 daily riders, Amtrak runs the equivalent of a midsize city—if that city were spread across 46 states, hundreds of stations, and 22,000 miles of track. The same crimes that happen in a city happen throughout a rail network: vandalism, disorderly conduct, theft.

Amtrak’s police department had been using GIS for years to understand and mitigate those incidents. Jennings and the team routinely created hot-spot maps of crime and steered Amtrak officers toward places where preventive policing might yield the biggest impact.

Now she was using the same technology to understand where suicides occurred. Through GIS, Jennings identified the exact location of every pedestrian incident and—by collating additional information such as coroners’ reports and video feeds—determined whether the event constituted a suicide.

She plotted all the events on a nationwide map, and patterns emerged. Clearly there were clusters—places where two or more people had committed suicide. The highest concentrations were in Florida, Illinois, and parts of California—the Bay Area and southern portions of the state.

Officials wondered why.

As Jennings deepened the GIS analysis, she saw clues: Some areas lacked fencing to keep pedestrians out. Other locations were close to homeless encampments near the tracks. In Carlsbad, California, a mental health facility sat near the site of several recent deaths.

By 2017, the investigation had revealed 150 sites—100 along tracks, another 50 at stations—where multiple suicides had taken place.

Using Data to Change the Course of a Life

Petito, her skepticism dimmed slightly by the insight she saw on the map, set to work. Her opportunities for action were complicated by the fact that Amtrak owns fewer than 1,000 miles of the 22,000 miles of track it travels; the rest it accesses through agreements with host railways. But through its own actions and the help of its rail partners, Amtrak worked to install access barriers where it could, and directed its officers to patrol other high-risk areas in hopes of deterring suicide attempts.

Still, many rail lines run on street level and cross pedestrian areas where physical barriers aren’t possible. So Petito and team also invoked a more direct tool. With guidance from Jennings, they installed suicide prevention messages in problem areas. About the size of a stop sign and visible even at night, the signs include the phone number of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-8255).

Petito knew just where to place them, thanks to Jennings’ analysis.

“If you have 22,000 miles of railroad and you’re just putting these out there willy-nilly, I’m not so sure you would have any kind of success,” Petito explains. “We’ve been able to place signs in the exact areas where these strikes have occurred.”

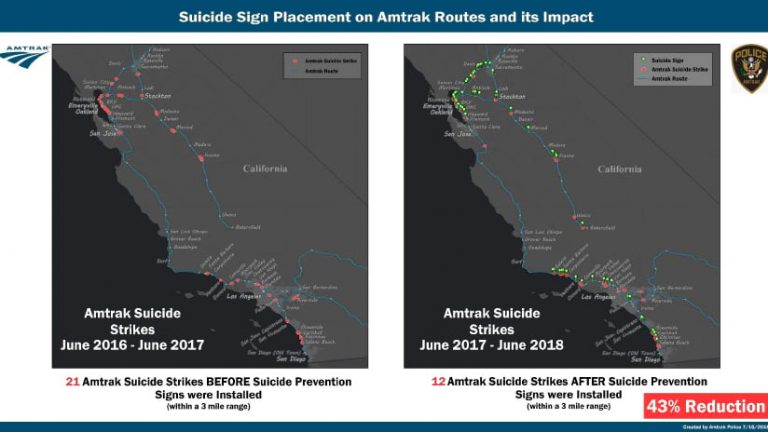

To the relief of Petito, Jennings, and all Amtrak professionals, the increase in the number of signs (222 at last count) coincided with a decrease in the number of suicides on the company’s tracks. From a total of 84 in 2017, the number dropped to 56 in 2018. In specific regions like California, the total went from 21 suicides in the year before the signs were installed to 12 the year after, a 43 percent drop (see image above).

Petito says she’s been heartened by the results, although she and Jennings caution that there’s no definitive proof the program alone is responsible. Still, “there’s a certain percentage of people who are attempting to commit suicide, that see a sign like this, offering help, offering an alternative, [and] they will respond to it,” Petito says. “So that’s what I can say may be happening here.”

In my mind, this is a success. I don't know if scientifically it could be documented as such. But if someone's responding to this, thank God we've done it, and I applaud the host railroads that have agreed to work with us on this program.

Seeing as a Company Grows

Creating visibility across 22,000 miles of track, 300,000 square miles of utility infrastructure, or a sprawling network of stores and offices can be a daunting challenge.

For Amtrak, the utility company, and many other organizations, GIS technology is producing location intelligence that helps decision-makers see problems clearly and understand how to react.

At Amtrak, it turned Petito into a believer.

“There is no question that without that technology, I wouldn’t even begin to try to claim any kind of success for this program.”

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

November 12, 2018 |

February 1, 2022 |

April 29, 2025 |

April 1, 2025 |