No coastal city in the world is immune to the effects of climate change, but if current trends continue, Boston will be among the first to bear the brunt. Rising sea levels are set to have profound impact on businesses near Boston’s historic harbor area. Executives considering locating their companies in this rapidly expanding area would be wise to use location intelligence to decide whether this is a smart move.

As Bloomberg Businessweek recently reported, Boston is the leading East Coast city for high-tide-related flooding, with an average of one incident per month—a nearly 300 percent increase over the rate 60 years ago.

Yet looming catastrophe does not appear to be dampening economic progress. The city’s Seaport District, once a crime-riddled area containing mostly parking lots and disused warehouses, is experiencing explosive growth that appears resistant to anxieties about climate change. The district’s rebirth began with the construction of a federal court building in 1999 and is culminating in massive projects worth $3 billion, spearheaded by the Massachusetts company WS Development.

Citing an analyst at Enki Research, Businessweek notes that the developed area of 1,000 acres represents an unsurpassed collection of expensive real estate. To cope with the area’s inevitably watery future, projects will include such safeguards as portable water barriers and lobby floors that can be elevated.

Those precautions raise questions about whether businesses will continue to migrate to such areas, and whether they should. To figure out the answers, companies will consider many variables. Location intelligence from a geographic information system (GIS) can provide analysis on current and projected data about specific locations, proving a crucial tool for these calculations.

The Lure of the Seaport

People want to live in cities like Boston. Such desirability drives up residential real estate prices while attracting the kind of educated elite workforce many companies value. These tendencies are mutually reinforcing: workers flock to the cities with strong economic prospects, and companies locate their offices where the workers live.

This is why, for instance, tech company PTC, after 30 years in the Boston suburbs, recently relocated to the Seaport—in part, to recruit augmented reality talent. The kind of young, tech-savvy employees PTC values are attracted to urban centers.

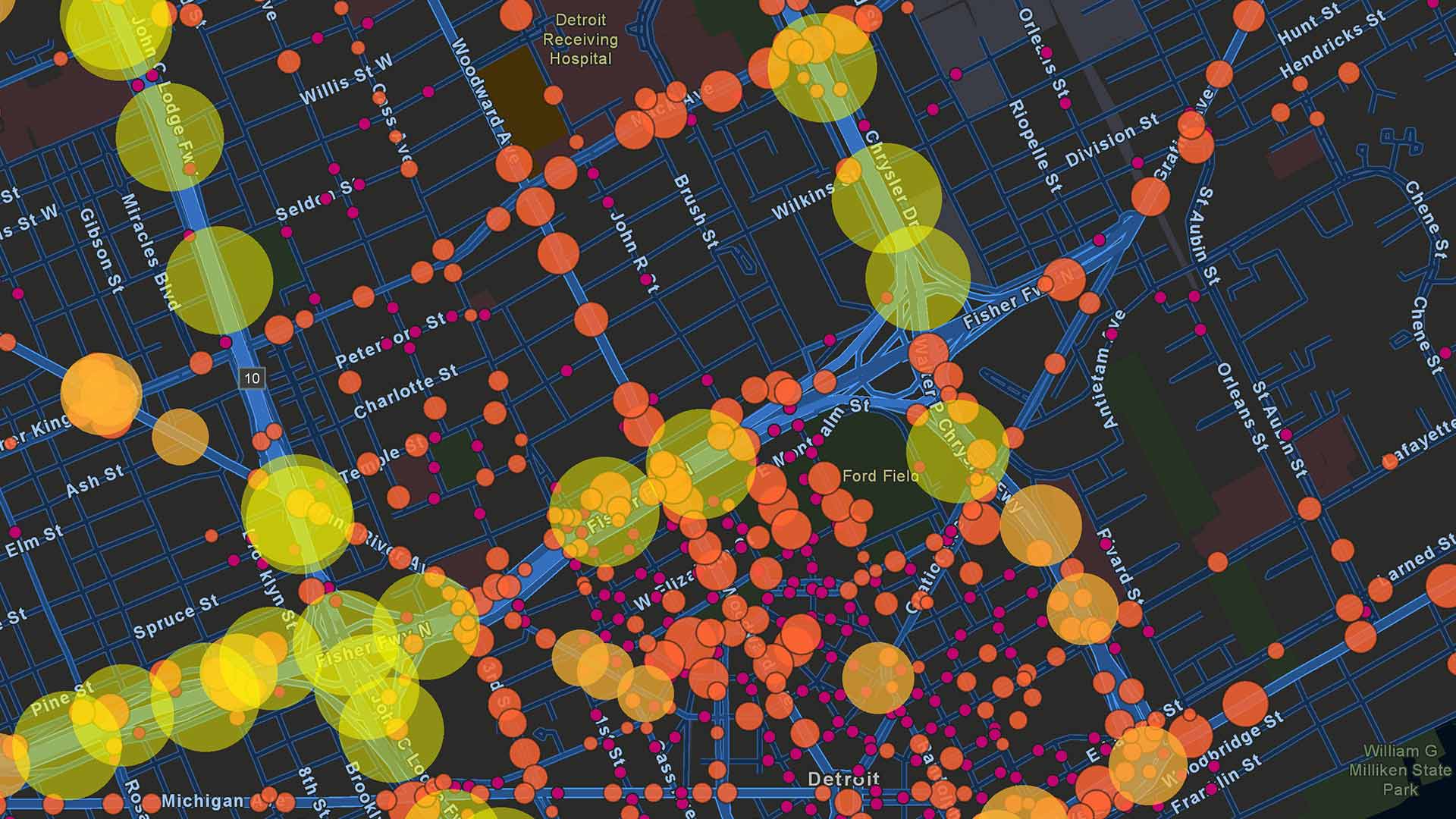

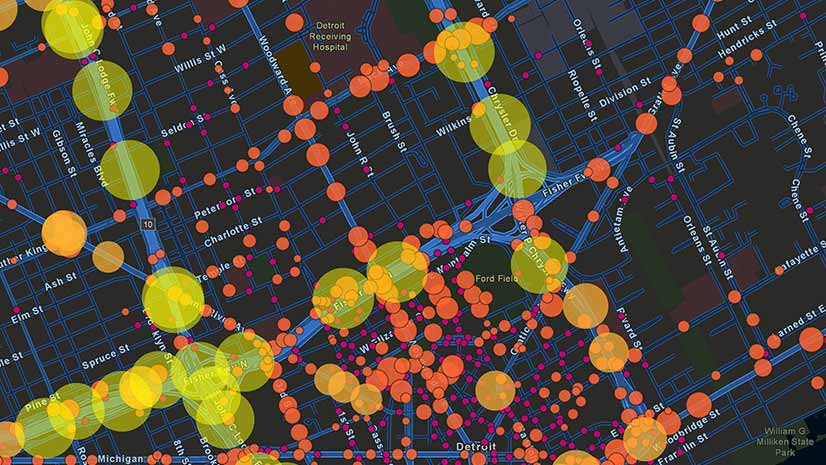

To make decisions about where to set down roots, top companies use tools that generate location intelligence. Using GIS software, for example, executives planning a company’s future can analyze where talent pools are coalescing and industry hubs are forming.

The calculus that has drawn many firms to Boston in recent decades won’t be right for all companies in the years ahead, which is why location intelligence will be such an essential tool. GIS-based location intelligence will allow executives to analyze the delicate intersection of where talent is emerging and how those locations are likely to be affected by climate change. Smart companies are already utilizing location intelligence to assess how new weather patterns will affect such variables as a company’s supply chain and technological infrastructure.

Balancing Risks, Protecting Assets

The smartest companies examine how climate changes will affect not only natural resources but also human resources. Those considering moving to locations in coastal cities or flood-prone areas will take advantage of growing networks of IoT sensors—including tools like the StormSense project—to get a better understanding of threats.

And they’ll need to balance the desires of workers with the financial realities of locating offices in vulnerable areas. Insurers are increasingly using location intelligence to quantify the cost of underwriting properties in threatened areas. A recent WhereNext article noted:

Location intelligence helps drive “point-based risk scoring,” which gives underwriters a more complete view of a property than they have traditionally had. Insurers might take into account everything from local soil composition to the types of trees in a nearby forest.

Climate change will increasingly figure into these calculations.

While GIS can help companies perform this kind of sophisticated analysis on a city’s predicted future, executives might also draw location intelligence from the more mundane objects in their midst. In Boston’s valuable Seaport District, for instance, the landscaping for the latest round of buildings will include an ode to glacial erratics, the hulking boulders that were left behind when the glaciers last receded.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

November 12, 2018 |

July 25, 2023 |

February 1, 2022 |

March 18, 2025 |

May 28, 2025 |