February 10, 2022

Ask Paul D. Graham about any of the 1,487 trees at the University of North Alabama (UNA) campus, and he’ll note their precise location, species, age, biometrics, and current condition. As an arborist, Graham has mapped trees for more than 20 years, most recently at the university as its manager of geographic information systems (GIS) and facilities information.

While lush campus landscapes can be a recruitment and retention tool—think study spots under shady canopies and naps under branches in between classes—Graham sees more. He’s taken his passion for trees a step further, using a geographic approach to transform campus vegetation management.

Graham knows which trees are likely to thrive in certain spots or soil types and which will restore needed biodiversity, and he keeps track with GIS. Urban forests, when designed right, help keep water from flooding or pooling at the surface which can affect the soil, impact future plant growth, and cause erosion. Also, urban forests play a role in mitigating global warming by capturing and storing carbon dioxide.

“Historically, the university has seen vegetation management as something to look at once or twice a year for pruning and removal,” Graham said. “With a database, I can show them where problems are, why costs might be higher on certain scenarios, how many trees we have, how many have been planted, or how many have been removed. They have a full picture.”

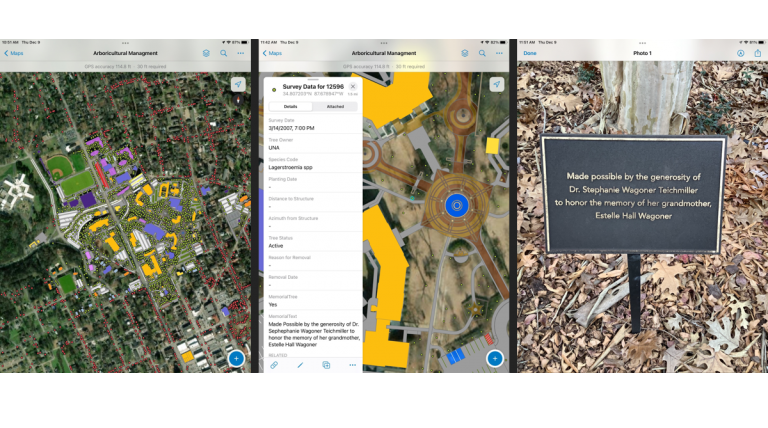

So far, Graham has mapped 79 species, 1,487 trees, and 42.79 acres of turf that make up the university’s 147-acre campus. It’s all part of the UNA Arboriculture Management Field Map. Graham uses it to address the wide variety of common challenges that come with managing urban forests such as removing diseased or risk-laden trees, diversifying the tree population in planning efforts, and scheduling routine maintenance.

“I’m all about attacking a problem with as much information as I can. That way I just come out with a better decision,” Graham said.

Graham’s interest in using digital maps for urban forestry stems from early in his career when, while conducting research, he ran into challenges identifying the right tree among a group on a paper map.

“A part of working in urban forestry is discerning identities of trees that are geographically close to one another,” Graham said. “Having a database with a geographical representation of the specimen, can help us triangulate the specimen and prevent classification mistakes.”

Already a believer in the power of maps for his industry, Graham accepted a position as an urban forester for the City of Florence in Alabama. In this role he used GIS to help complete a survey of 37,000 trees, which included UNA campus trees. Later, he strengthened his understanding of GIS while working as the UNA grounds superintendent and completing his master’s degree. Finally, Graham put all that education and experience together to create the first digital map of the campus and its trees.

“Landscapes are always in a state of flux, and as an arborist, you need to know where you are in that state of change,” Graham said. “The idea was to create a database that could be visualized and analyzed.”

Now, Graham makes the UNA Arboriculture Management Field Map available to anyone on campus. It functions as a dynamic management database with a 2D map of buildings, roads, crosswalks, parking lots, as well as iconography representing trees, plant species, and turf. Users can click on a tree icon and pull all the data associated with it such as the tree’s biometrics, history of planting or removal, measurements, tree events (early care, stake removal, pruning, and occasional vandalism), and potential risk factors like disease or overgrowth that could cause tree branches to fall. Images for each tree are also layered on the map so stressed or diseased trees can be visually tracked.

“Having this historical record provides us with the data to look at decline trends and determine if the cause is acute to the specimen or an environmental effect that must be accounted for and watched,” Graham said.

The university strives for a 1:1 replacement ratio of all trees. Graham’s management system empowers him to budget for new species that improve campus biodiversity and sustainability. For instance, he can select trees more tolerant to environmental stressors and climate change.

Not only does the database provide a form of institutional memory and overview for all campus vegetation, but it can also be easily shared with contractors for construction or tree removal work. “We use the database to identify specimen conditions that require work and can share the maps to communicate the locations and specific details of the job,” Graham said.

Since the creation of the map, UNA Facilities Administration and Planning Grounds department has partnered with the City of Florence Planning Department, Urban Forestry and Horticulture Department, Parks and Recreation Department, and Florence Electricity Department. The City of Florence and UNA’s tree datasets are shared among entities for asset management, tree removal, and collaborative projects.

“University campuses are an extension of the community in which they are located,” Graham said. “The landscape, vegetation and urban forest management practices at the university seek to add value to not only the campus but the city of Florence, Alabama and the region as a whole.”

For Graham, the database, demonstrates the utility of trees beyond landscape aesthetics. The arboriculture management system includes data highlighting net positive benefits like the top tree species on campus, carbon emissions in metric tons, carbon sequestration dollar value, and total overflow surface water prevented.

“We are in the process of demonstrating to the administrators and directors the values of the maps,” said Graham. “What we have now is good, and there is some acknowledgment that the data is valid and great for operational purposes— but we also want to show administrators the current value of our urban forest.”

The system’s relational datasets are easier to understand when visualized and communicated as charts, gauges, and maps of people, services, and assets in real-time and displayed in a dashboard environment.

“Having the ability to provide reports in a variety of formats, including the spatial context, is a big help,” Graham said.

All forest management is driven by changes in the season, and increasingly by awareness of climate change. Graham has found GIS to be invaluable for having the right information at the right time for vegetation management and hopes other municipalities and universities adopt this data-driven approach.

“I would like this to become a solution for others beyond our collaborators in Florence, because there is an opportunity to use this as a jumping-off point for all urban forests,” Graham said.

Learn more about how foresters use GIS for sustainable forest management.