We're all islanders on island earth.

November 2, 2021

By

Nobody is immune to the effects of climate change, but for island communities there really is no escape from the rising waters. “If you try to retreat,” Celeste Connors likes to say, “you quickly hit the other side of the island.”

As executive director of Hawaiʻi Green Growth Local2030 Hub (HGG), Connors is hyperaware of climate impact for the islands. HGG oversees the Aloha+ Challenge, a statewide effort to address the United Nations’ call to achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs) by 2030. Aloha+ sets major goals—involving clean energy, local food production, resource management, waste reduction, and sustainable approaches to education, workforce, and community management—designed to be reinforcing and interconnected.

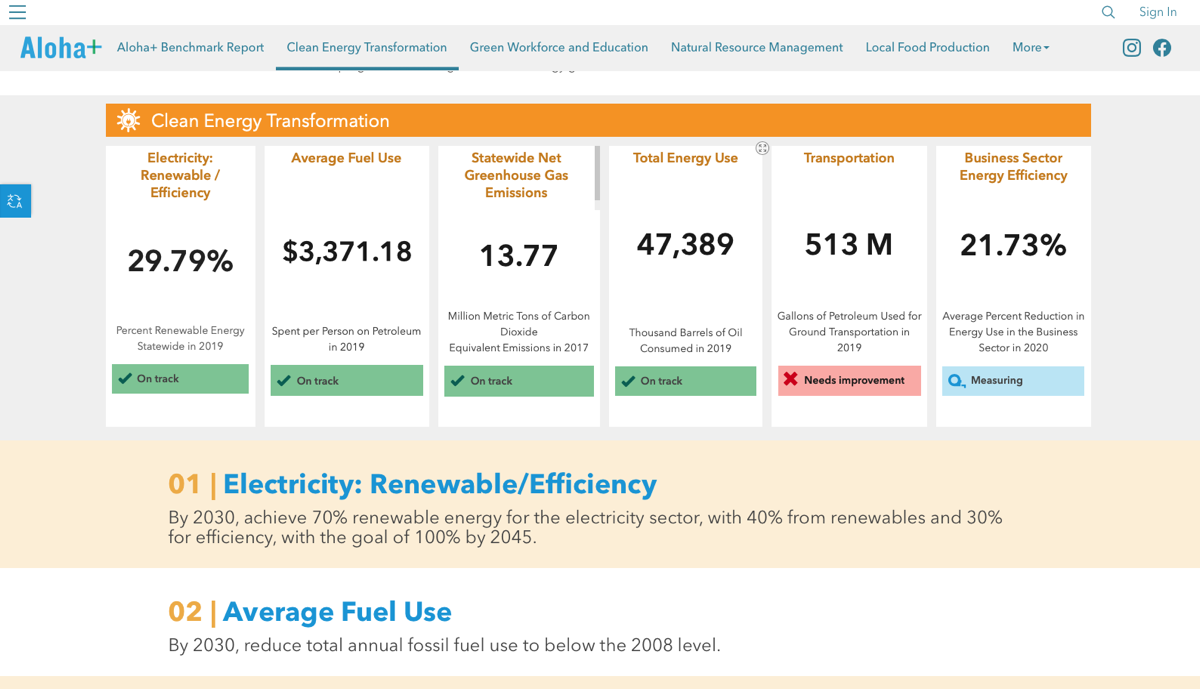

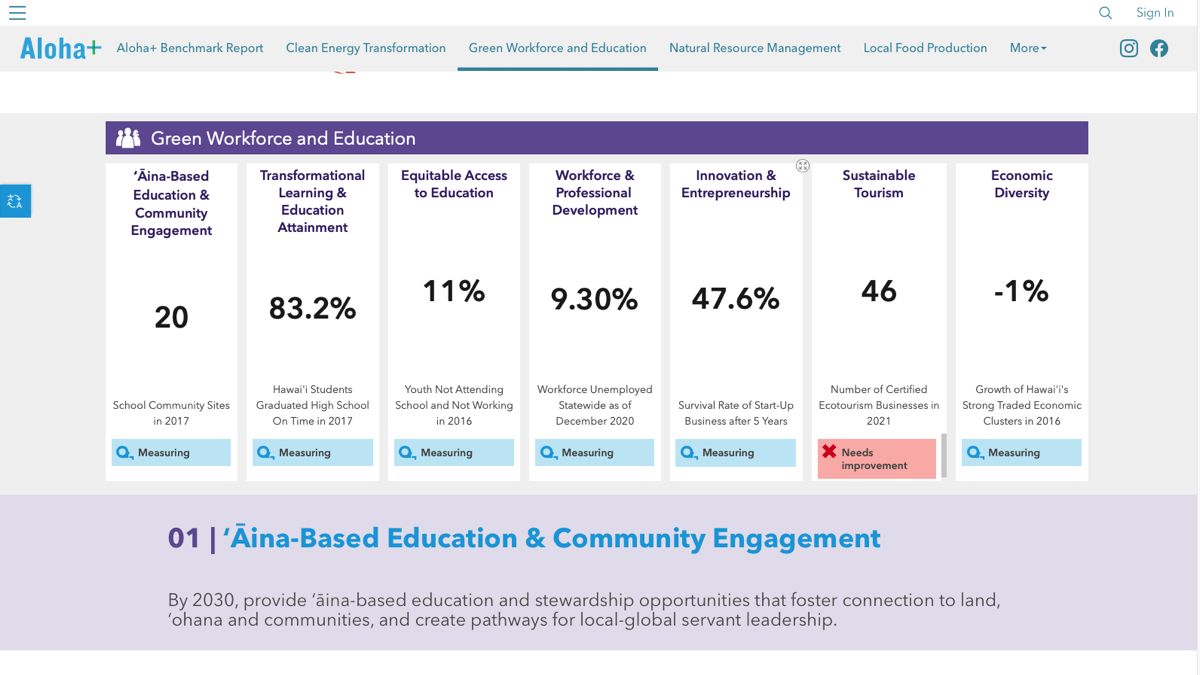

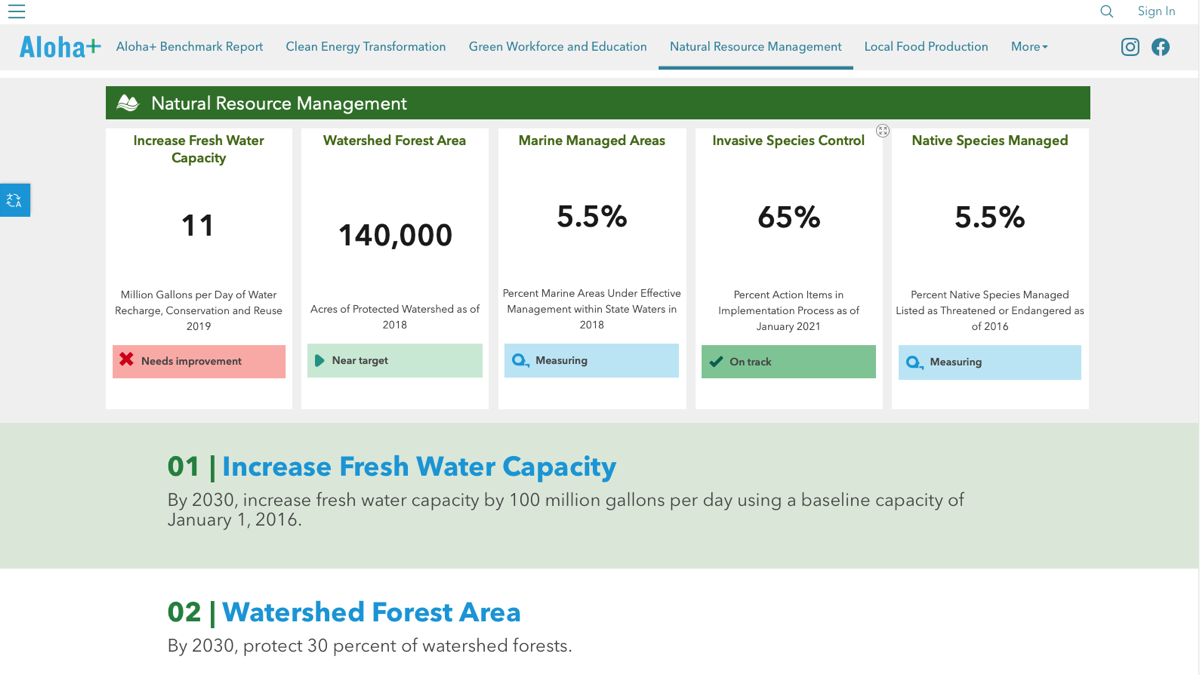

To meet the 2030 deadline, Connors and her team track progress toward the SDGs via a dashboard built on a geographic information system (GIS). They use the online tool to monitor Aloha+ Challenge’s objectives in the context of agreed-upon metrics.

“GIS, to my mind, allows you to reunite the head—the data—with the heart,” Connors said. “You can add the story and context and values to the science. And when you combine them, that’s when you actually inspire behavioral change.”

The Aloha+ Challenge is the culmination of more than ten years of climate activism among island nations. In 2005, a decade before the UN finalized its SDGs, Palau President Thomas Remengesau Jr. announced his country would commit to conserving at least 30 percent of near-shore marine resources and 20 percent of terrestrial resources by 2020. He challenged other leaders of island nations in the western Pacific Ocean to do the same.

His call led to the launch of the Micronesia Challenge the following year.

With the help of the Global Island Partnership (GLISPA), officials from the Marshall Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, and the Federated States of Micronesia joined Palau in pledging the same goals for marine and terrestrial conservation. They’ve since increased those goals to 50 percent and 30 percent, respectively, by 2030. Last year Palau opened a marine sanctuary that protects 80 percent of the country’s national waters, an area larger than the state of California.

We're all islanders on island earth.

“The Micronesia Challenge was really transformational, because they had actual numbers and milestones,” Connors said. “The leaders were saying that regardless of what happens—or, likely, doesn’t happen—in climate negotiations, they would make a commitment to steward their land and water resources.”

In 2008, 11 Caribbean countries launched the Caribbean Challenge Initiative, pledging similar goals.

During that same year, Connors began working in the new administration of President Barack Obama. As the director for climate change and environment at the National Security Council, she helped develop the SDGs, and was also involved in preparations for the US to enter the Paris Agreement climate change treaty.

It was all part of an extended journey away from Hawaiʻi, where Connors had grown up before she left to attend Tufts University in Massachusetts. Before reaching the White House, she was New York City’s foreign affairs officer and did diplomatic work for the US State Department that led her to Greece, Germany, and Saudi Arabia.

After leaving the administration near the end of President Obama’s first term, Connors taught at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies and cofounded a sustainable infrastructure consultancy.

Around that time, leaders of the GLISPA were thinking of their next steps in response to climate change and biodiversity loss. Involving Hawaiʻi would build on the Micronesia and Caribbean efforts, while connecting them with the broader industrialized world.

“The Aloha+ Challenge was the US and Hawaiʻi response to helping build a model for sustainability,” Connors said. They offered Connors the job of leading it. After 20 years away, she was eager to come home and contribute to Hawaiʻi’s future.

The “+” in Aloha+ Challenge is significant, representing an effort to create a holistic approach to sustainability, much like the UN’s objectives with the SDGs. “Despite our name, Hawaiʻi Green Growth is not an environmental group,” Connors explained.

Along with environmental goals, the Aloha+ Challenge involves hitting benchmarks related to equity, economic prosperity, affordable housing, and education. “I think the SDGs are the new economic, social, and political framework,” she said. “Climate change is the force multiplier, exacerbating broader tensions. It shouldn’t be seen as an individual silo.”

It wasn’t until Connors had returned to Hawaiʻi that she realized this philosophy, deeply ingrained in her upbringing, was part of what led her back home. “It was like, of course we need a systems approach,” she said. “Silos make no sense when you grow up on an island, because you know what happens in your upper watershed affects your coral reef and everything in between.”

A clue to the deep local origins of that philosophy lies in one aspect of the Aloha+ Challenge’s smart, sustainable community goal: connection to place. Explanatory text on the GIS dashboard reads “Ahupuaʻa Managed With Community-Based Plans.”

Until King Kamehameha III instituted a universal system of private land ownership in the mid-19th Century, every island in the Hawaiian Kingdom was divided into many semi-communal ahupuaʻa (ahu-pu-AH-ah). An ahupuaʻa was a slice of land that typically extended from a mountaintop to the coast.

Each ahupuaʻa was, to some degree, a closed system, encompassing within its borders every kind of local climate and terrain, and therefore capable of producing everything its residents required to live. Subjects paid taxes to a local chief for the right to farm, hunt, or harvest fish.

The Hawaiians believed the relative self-sufficiency of the ahupuaʻa maintained a crucial balance and interconnectedness. A problem in any one section affected every person’s ability to have access to life’s necessities.

Integral to the system was a concept called kuleana (koo-lee-AH-na), which translates as “responsibility” but refers specifically to a reciprocal relationship. People were responsible for caring for the land, which in turn was responsible for producing necessities of life.

Kuleana even extended to social relations. In return for the taxes paid to work the land, the chief was expected to maintain harmony.

Kuleana, Connors realized, was a local value she had internalized as a child and held close throughout her life. “Growing up here, whether you’re native Hawaiian or not, it’s just something you’re taught,” she said. “What people call a circular economy, we call an island economy.”

In its own way, the Aloha+ Challenge dashboard provides an outlet for a geographic approach as vivid as any map. With the ahupuaʻa system in the distant past, the dashboard treats the state of Hawaiʻi as a kind of single massive ahupuaʻa. To look at the dashboard—to see the goals and the progress made—is to witness an island community striving to create and maintain balance.

So far, according to the dashboard, environmental goals, especially clean energy transformation, are where the state is making the most progress. Benchmarks for renewable electricity, average fuel use, greenhouse gas emissions, and overall fuel use are on track for the 2030 goal. For the natural resource management goal, the amount of watershed forest area is already nearing the target, though water conservation and reuse measures need improvement.

The more human-centered parts of the dashboard, particularly those measuring livability and resilience, reveal the elusiveness of kuleana in a complex global economy; not surprising in a state with one of the highest supplemental poverty rates (a metric that weighs cost of living) and the nation’s largest per capita unhoused population.

Look closely, and the dashboard even tells stories about Hawaiʻi’s history. The goal of increasing agricultural acreage and doubling local food production has lagged. The reasons are complex, but partially reflect the many decades when most farmland was owned by a few large companies producing commodities, such as sugar and pineapple, primarily for export.

In 2018, a few years after the finalization of the SDGs, the UN decided a local approach was the best hope for achieving the goals by 2030. In the same way that island nations had set their own benchmarks years before the SDGs, it was important to let localities take the initiative in helping to reach global goals.

To highlight places where this approach was yielding strong dividends, the UN designated Local2030 hubs around the world, including cities in Sweden, Brazil, Japan, and the United Kingdom. Hawaiʻi Green Growth is the only Local2030 hub among North American nations, and the only island hub in the world.

HGG is currently helping to link islands across the globe, from Guam and Puerto Rico to Ireland and Grenada, as part of the Local2030 Islands Network. The goal, Connors explained, is “to see US leadership through an island lens.”

In 2014, the UN honored Thomas Remengesau, the Palau president whose example sparked the global island activisim that continues today, with its highest environmental accolade, the Champion of the Earth award.

“To solve the SDGs, I believe you need to think like an islander,” Connors said, before quoting an aphorism she attributes to Remengesau: “we’re all islanders on Island Earth.”

Learn more about how GIS connects society, environment, and economy to advance SDGs.

Jen Van Deusen led the Sustainable Development Industry Solutions team at Esri. She focused on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and telling and sharing the stories of community stakeholders who are applying GIS to achieve the SDGs. Jen’s background combines business, nonprofit leadership, and cross-sector collaboration in applying technology to achieve sustainable development in the infrastructure/AEC space, with efforts ranging from energy renewables and optimization for AEC, sustainable infrastructure in small island developing states (SIDS), to clean water access in developing communities. She has lived/worked internationally, and, as an alum of Brown University and IE University, also works with these institutions to partner with nonprofits and for-profit entrepreneurs to achieve positive impact in under-served communities in Ethiopia.