Pat Dolan and his wife, Mara, are experts at navigating long days.

After his 2016 diagnosis for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)—also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease—the couple learned that the neurodegenerative disease requires continuous multidisciplinary care. This involves spending entire days throughout the year receiving treatments and therapies at an ALS clinic. While exhausting, care continuity is critical for ALS patients, which makes having a nearby clinic crucial.

On one such visit, while the Dolans sat in the lobby at Loma Linda University Health Center for Restorative Neurology in Loma Linda, California, a few miles from their home, they struck up conversations with the other patients to pass the time.

One couple said they traveled 170 miles from Bakersfield, California, to Loma Linda every three months to receive the closest clinic care available. Another woman said she drove herself 80 miles round trip. Her exhaustion was palpable, and her concerns about driving home alone after a day of treatment during rush hour traffic were well-founded. But she had no other choice, as this was the nearest clinic.

“It was unbelievable,” Mara Dolan said. “The stuff we saw was just so heartbreaking, but it made us feel so lucky to be where we were, and we just wanted to help them somehow.”

Pat Dolan instinctively knew he needed to apply GIS to the problem. As a former solutions team lead at Esri, Dolan had spent his 25-year GIS career creatively using the technology to solve real-world problems in the utility industry. He even lent his expertise to collaborate on the 2014 movie Godzilla to ensure that the script represented GIS technology realistically—or “[as] realistically as you can, chasing giant monsters,” Dolan said. His career enriched his understanding of the world and empowered his approach to overcoming unique challenges, including being diagnosed with ALS.

“I wanted to continue contributing to society, and I hope my GIS skills and work continue to contribute in a small way,” Dolan said.

Moved by conversations with other people with ALS—known within the ALS community as pALS—as well as his own experience trying to locate clinics, support groups, and medical trials, Dolan quickly began applying GIS technology to support the ALS community. For example, where were the ALS clinics in the United States, and how could pALs across the country easily find the ones closest to them on a map?

“Location is everything for the chronically ill, and—amazingly enough—this information wasn’t mapped,” Dolan said.

He first began by mapping the location of ALS clinics across the country to understand the pattern of care in the United States and help others find their closest clinic. Inspired by a friend who created a brewery locator that enabled a survey component, Dolan decided to use his GIS skills to create a similar resource for his community.

“I thought this [brewery locator] was a brilliant idea and wanted to provide the same capabilities to enable pALS and cALS [caregivers for people with ALS] to find their clinic and gain insights on the services that are so important to the ALS community,” Dolan said. “If we can find a brewery, we should be able to find a clinic.”

Dolan built the ALS Clinic Locator & Survey web app with ArcGIS Web AppBuilder and ArcGIS Survey123. The app gives pALS and cALS nationwide the ability to find the location of the clinics closest to them, using a street address or just a ZIP code.

For example, typing the 92373 ZIP code in the location box and 60 miles in the search distance box will bring up four ALS clinics in the Redlands, California, area, marked by red symbols on a map and listed on the right side of the screen. Both the map and the list include a pop-up information box with the name and address of each clinic and the approximate distance to the clinic from the searcher’s location.

The site can be navigated by those with eye-tracking devices (frequently used in the ALS community) and includes an optional survey for pALS to share their experiences about the care they receive at clinics. Moreover, the app provides a holistic view of more than 200 clinics across the United States—a function Dolan considers vital, since many diagnosed with ALS consider moving to be closer to family or may need to relocate altogether from states without a clinic.

“By having this information, it helps patients like me have a sense of hope and gives us the opportunity to put an action plan together,” Dolan said. “The app shows location of care and enables [pALS] to provide feedback to the care providers; my hope is that it will become a common pattern in the health-care industry to do so.”

Creating a Sense of Urgency

In April 2021—ahead of ALS Awareness Month in May—Dolan saw an opportunity to not only launch his app but also push for the passage of proposed legislation that would offer more opportunities for faster therapies and broaden access to those who need it most. The legislation, S.1813 in the United States Senate and H.R. 3537 in the United States House of Representatives, is an updated version of the Accelerating Access to Critical Therapies for ALS Act, also known as the Act for ALS.

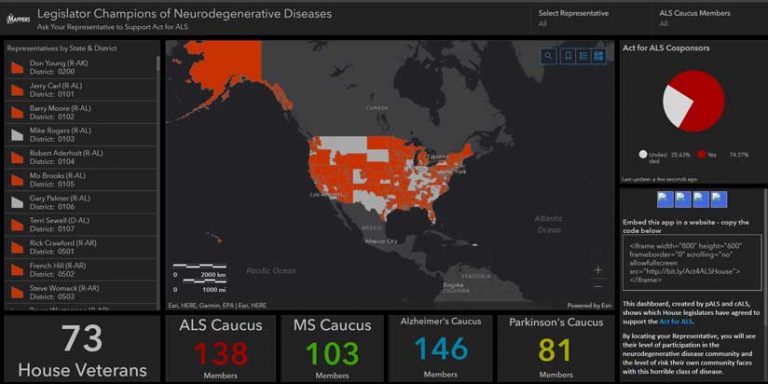

What began as Dolan asking friends and family on social media to see if their congressional district members were cosponsoring the act evolved into creating a dashboard that tracked and monitored which lawmakers signed on to the legislation. Focusing first on the House bill, Dolan included details on the 138 members of the ALS Caucus to encourage their advocacy. [The ALS Congressional Caucus is a bipartisan group of champions on Capitol Hill who are leading the federal fight to end ALS.] Dolan also included ways to contact 73 military veterans who serve in the US House of Representatives, since those who serve in the military are twice as likely to be diagnosed with ALS, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. He also highlighted those members who had supported the original act in 2020, as a gentle reminder to them to offer continued support.

To inspire action, Dolan enriched the Legislator Champions of Neurodegenerative Diseases dashboard (https://bit.ly/3uuIrvH), built using ArcGIS Dashboards, with demographic data showing the number of veterans and residents over the age of 55 years—the people who are at the greatest risk of ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis—living in each representative’s district. Dolan also leveraged his ALS Clinics dataset to summarize the number of clinics per district. The goal was to inspire action and simplify the process for people to ask their representatives to support the legislation. He followed the same pattern with the Senate Champions of Neurodegenerative Diseases dashboard.

“My hope is that these maps will create a sense of urgency and the need to support the act,” Dolan said.

First, though, Dolan needed assistance with coding the functionalities of both his app and the dashboard. He turned to a longtime collaborator, Amanda Stanko, a solutions engineer at Esri, to launch them. The pair worked for three weeks, communicating primarily through instant messaging and email, to build the dashboard and app.

“Pat had carefully thought this out and knew exactly what he wanted,” Stanko said. “[Building the resources] was intense, but even with tight deadlines, it was great because we had this energy and drive going, and we were having a great time.”

Stanko said the combined map and legislative dashboard have more impact than a static spreadsheet might. “To see [information] visualized on a map helps you understand so much more quickly the impact [of] how few clinics there are or how many votes are still needed,” she said.

Dolan said Stanko’s involvement was key. “Not being able to talk and relying only on my eye-gaze device to type out my response can be very frustrating and exhausting at times,” he said. “Fortunately, Amanda is extremely patient and was able to take my half-baked ideas and turn them into an amazing solution. Working with her inspired me to continue pushing myself to be the best GIS professional I can be.”

Stanko called Dolan “a hero of mine” and added, “To keep working to make change in his community and spread that information is just amazing.”

Persevering with Passionate Work

ALS has no cure. According to the Johns Hopkins Medicine website, 30,000 adults in the United States are living with ALS. The neurodegenerative disease affects nerve cells, causing muscles throughout the body to stop working; this leads to weakness, then full paralysis, including the inability to breathe or talk. After diagnosis, a person typically lives from two to five years with the disease, but that time can vary with age.

In addition to attending support groups and visiting ALS clinics routinely throughout the year, successful treatment relies on a holistic approach to care such as promoting a healthy mindset. Mara Dolan said her husband’s ability to keep mapping and giving back has been vital in managing the stress of and treatment for ALS.

“We all have our own ways of handling the hard things; Pat’s [way] is working on maps—maps that will help other people,” she said. “If I walk into the room while he is working on maps, I can see it in his eyes—he is happy. Maps take ALS out of his picture as much as possible in those moments, which is wonderful.”

To learn more about ALS and join the ALS movement, please become a member of I AM ALS.

Watch Pat Dolan’s 2017 presentation on using GIS for supporting pALS.