Researchers Use ArcGIS to Evaluate Impact of On-Site Social Programs on Affordable Housing Residents

California is in an affordable housing crisis. The Golden State has the second-lowest home ownership rate and the second-highest median property value in the United States. Although the fiscal challenges of home ownership drive more than 40 percent of the state’s residents to rent, California’s average monthly rent is 50 percent higher than the rest of the country.

Take Orange County, for example. This county of 3.1 million residents is one of the most expensive rental markets in the United States, with 90 percent of very low-income households reportedly spending at least one-third of their income on rent each month.

Building affordable, multifamily housing could provide many socioeconomic benefits to Orange County’s low-income residents, though, according to a 2014 report commissioned by state housing authorities. Affordable housing has been shown to decrease residential instability and enhance educational outcomes for children. It also reduces pressure on household budgets so that families have more discretionary income to spend on food, health care, and other basic living expenses.

Even so, securing stable housing is only half the battle, given that more than 4 million US families living in government-assisted rental units earn less than 30 percent of their area’s median income, according to the National Resident Services Collaborative. Thus health and education challenges abound for many low-income families in affordable housing.

That is why researchers at the University of Southern California (USC) School of Social Work recently applied geography to examine whether a service-enriched housing model—which provides on-site social services to residents—could minimize socioeconomic, educational, and health disparities for children and families living in affordable housing communities.

Can On-Site Social Services Narrow the Rift?

To see if providing hyperlocal educational, nutritional, and health assistance to low-income residents would make a difference, the research team sought out three affordable housing sites in Orange County to test the model.

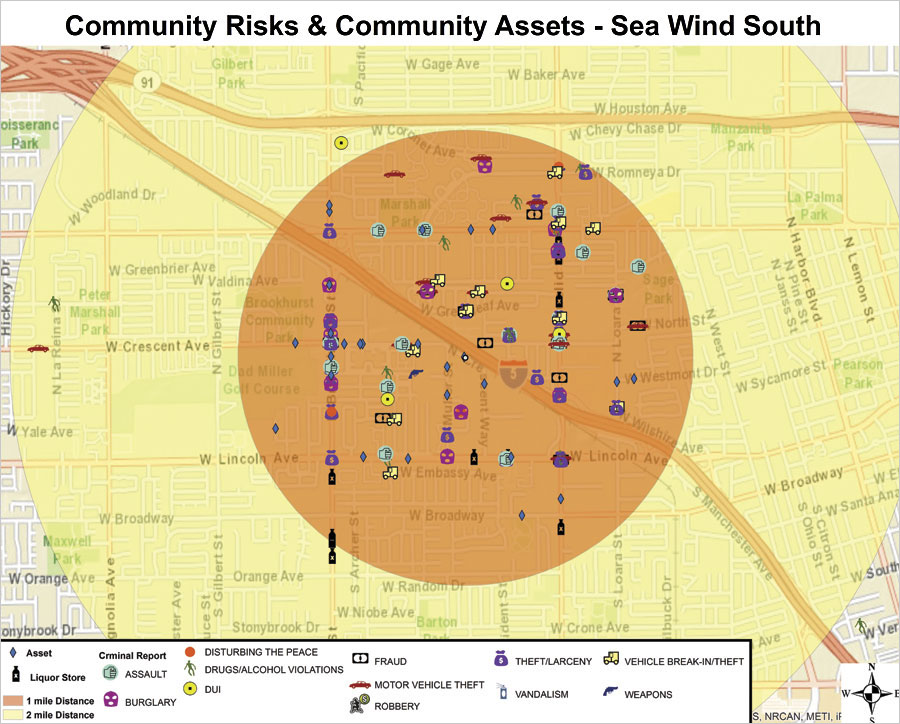

The team used data available through Esri’s ArcGIS platform to identify three sites that were comparable in location and composed of similar populations: predominantly low-income, Hispanic residents. Once the three apartment complexes were selected, researchers employed ArcGIS for Desktop to map the key assets and risks within a one-mile radius of each location. Assets included the number of neighboring parks, schools, grocery stores, and recreational centers, while risks comprised the quantity of nearby liquor stores and local crime rates (taken from the total number of police reports made during the month of June 2014).

Teaming up with Project Access, a nonprofit that specializes in residential services for low-income families, the researchers decided to administer different doses of adult nutrition classes and after-school youth programming to each of the three housing complexes. The experimental site received full-time services, the comparison site received part-time programming, and the control location was given no services at all.

The team’s ArcGIS maps displayed the sites’ tallies of assets and risks. For the sites that received full-time and no services, results were comparable: they each had more than 100 criminal activities with varying degrees of severity reported to local authorities throughout the one-month time frame. The part-time site, however, only had one criminal activity reported for the month—nonaggravated assault. Moreover, the part-time site had few risk factors altogether. This data on the sites’ sociogeographic variations proved to be vital when analyzing the study’s outcomes.

Connecting Location with Program Performance

Although the three-year study is ongoing and researchers are continuing to collect data, results for the first year revealed stark differences among the three locations.

Researchers discovered that residents at the full-time programming site strongly outperformed the other two sites, achieving more considerable gains in developing and maintaining positive relationships, contributing to community integration, and working toward healthier lifestyles.

Tenants in the full-time group also experienced higher satisfaction rates with their programs. Residents from the other two sites voiced concern about the lack of services and support systems in their complexes. At the part-time site, participants said they wanted more program hours and better scheduling flexibility. Residents who received no programming at all expressed a strong desire to participate in social programs but cited lack of transportation, long waiting lists, and high costs as reasons why they could not take advantage of similar services being offered elsewhere.

According to the first-year investigation, full-time social services do have a significant impact on the lives of low-income families—especially when it comes to their sense of community; making better lifestyle choices, such as eating well and exercising regularly; and perceptions as to whether their needs are being met. However, part-time and no-services participants had much lower—and nearly identical—perceptions of their quality of life and respective communities. This is especially telling considering that the part-time site is situated in an area with a much lower crime rate than the other two sites.

Geospatial Analysis Confers Credibility

Social science studies conducted in the field differ from those done inside a laboratory because researchers cannot control every variable. In these instances, it is pertinent to consider any influencing factors that might alter the study’s outcome.

For this research project, it would have been ideal—albeit unrealistic—to have comparable crime rates across all three sites at the outset. However, employing geospatial analysis lent credence to the researchers’ conclusion that part-time services may be less impactful on residents’ quality of life than full-time services.

Because the full-time group appears to have received greater benefits from its social services, researchers determined that the number of community risks identified in ArcGIS at the outset of the project did not impact the on-site programming. It was revealing, too, that although low-income communities have to combat multiple risk factors—including poverty, crime, lack of resources, navigation of public services, and language—full-time, on-site services appear to go a long way toward improving educational and health outcomes.

In the long run, researchers hope that this study can advocate policy changes for affordable housing. It has important implications for social policy, as the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee, part of the state treasurer’s office, awards tax credit points to housing developers that provide different levels of social programming. Since GIS helped illustrate that full-time services may have more substantial impact than part-time services—despite sociogeographic variables—the research team recommends that the committee reconsider the quantity of award points given for supplying part-time programming.

For more information on this study, contact USC professor and researcher Dr. Juan Araque.