|

On Saturday, February 1, 2003, Jeff Williams, then a graduate research assistant at the Forest Resources Institute (FRI), a research group within the Arthur Temple College of Forestry at Stephen F. Austin University, took his four dogs on their customary early morning walk through the woods in northeastern Nacogdoches County in eastern Texas. Suddenly, all wildlife ceased their usual morning clamor. The woods were silent and then it happened. A tremendous blast nearly knocked Williams to the ground. The trees were swaying, the dogs scattered, and Williams realized that he was running. The terrifying noise continued with successive explosions and blasts. It was 8:00 in the morning. On Saturday, February 1, 2003, Jeff Williams, then a graduate research assistant at the Forest Resources Institute (FRI), a research group within the Arthur Temple College of Forestry at Stephen F. Austin University, took his four dogs on their customary early morning walk through the woods in northeastern Nacogdoches County in eastern Texas. Suddenly, all wildlife ceased their usual morning clamor. The woods were silent and then it happened. A tremendous blast nearly knocked Williams to the ground. The trees were swaying, the dogs scattered, and Williams realized that he was running. The terrifying noise continued with successive explosions and blasts. It was 8:00 in the morning.

Several miles away, P.R. Blackwell, information scientist at FRI, was enjoying a second cup of coffee in the kitchen with his wife. He heard the explosion and felt the house walls shake. He went outside and looked around but did not see anything out of the ordinary. He went back into his home, turned on his television, and saw the early announcements. "The reporters were not sure what was happening, but those of us who heard the explosions knew," explains Blackwell.

| |

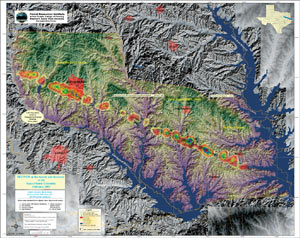

Debris density over 10-meter DEM produced for environmental hazards modeling. (Map courtesy of Forest Resources Institute. Digital Elevation Model courtesy of USGS. Vector data courtesy of Texas Natural Resources Information Systems.) |

The space shuttle routinely flies over Nacogdoches County in eastern Texas on its way to land in Florida and was expected to fly over that morning. Shortly after the explosions, Williams called Blackwell to discuss the situation. They knew that the Space Shuttle Columbia and the STS-107 crew had gone down in disaster. They said good-bye to their families and headed into the office for what was to become a 14-day geospatial first response effort. It was 8:15 a.m.

Gregg Fuselier, a special project coordinator at the Humanities Urban Environmental Sciences (HUES) GIS lab at Stephen F. Austin University at the time of the disaster, was at his Nacogdoches County home watching the gold finches at his bird feeder. Suddenly they flew away. He thought that a feral cat was nearby, but then his house began to shake. He experienced a series of very severe shocks.

"I could only relate to a refinery explosion since I am originally from the Gulf Coast," explains Fuselier. He and his wife went outside and saw a huge swirling contrail unlike any they had ever seen before. A few moments later, he received a call from Tred Riggs, a colleague from the HUES lab. "We knew we had to start mobilizing," says Fuselier. He called Dr. Darrel McDonald, professor of geography and the HUES GIS lab coordinator, and told him they were heading to the lab.

"My first thought was that whatever had happened was a localized event and that local mapping would be needed," explains Williams. Stephen F. Austin University maintains site licenses of both Esri's ArcGIS software and Esri Business Partner Leica Geosystems' ERDAS IMAGINE software. The FRI and HUES labs routinely use the software for teaching as well as research.

"Usually we all have multiple sessions of each software running simultaneously," says Blackwell. "We used these products in our work, and we were able to use these technologies as geospatial first responders during the emergency."

"We didn't know the extent or the scope of the situation initially," continues Williams. "It just kept getting larger and larger as the days went on."

Nacogdoches County is in the western extension of the southern pine forest in the United States and is a heavily forested, rural area with a lot of water features, such as deep river bottoms, lakes, swamps, rivers, bayous, and marshes. As was soon discovered, the shuttle broke up upon reentry and most of the debris came down in national forests and on forested private land. This topography makes for especially difficult search and recovery efforts.

"Much of the very early mapping work was done by Jeff," says Blackwell. When Williams arrived at FRI, he immediately began plotting a current Landsat 7 satellite image map of Nacogdoches County, which he coincidentally used in ERDAS IMAGINE for an FRI research project the previous evening. Williams explains, "At 9:15 a.m. the first set of satellite-based locator maps were packaged and delivered to the Nacogdoches County Emergency Operations Center (EOC) by Dr. James C. Kroll, FRI's director." Then a high-resolution basemap for the city of Nacogdoches was composed using a January 4, 2003, QuickBird image and ArcInfo. Annotation of features, such as roads, streams, and physical features, were then added to the current Landsat 7 image. FRI staff soon began to arrive.

| |

FRI staffer Terry Corbett (center) uses a map to point out current conditions to search and recovery team. (Photo by Hardy Meredith/SFASU Public Affairs.) |

The lab staff began moving in a frenzied state of production to deliver maps to EOC every couple of hours. "We started gathering points from incident reports faxed by 911 call operators," says Blackwell. "We had the procedures to work with the 911 operators in place because of recent regional hazard mitigation planning." Around 10:30 a.m. Williams and others began to set up mapping environments in ArcInfo to plot the 911 call report data.

"The process of what we call 'east Texas geocoding' commenced," adds Blackwell. "We were gathering data and plotting by best guess using ArcInfo, then providing the resulting maps to the search and recovery crews."

"We could easily geocode calls that were associated with an address," says Williams. "But approximately one out of three calls required geocoding based on a description." The calls listed places such as the "watermelon patch on Brewers Ferry Road," "the creek at Spanish Bluffs," "a quarter mile down Skillern Cemetery Road," or "the second white house past the Nazarene Cemetery." Along with the use of high-resolution aerial photography from the county, satellite imagery, digital orthophoto quarter quadrangles, and an old map with old road names, Williams' local knowledge of the landscape was essential to accurate placement of "best-fit" geocoding.

Kroll called from EOC to tell the FRI staff that Space Shuttle Columbia debris was all over the city and county of Nacogdoches. Fuselier had been organizing the GPS equipment at the HUES lab. Fuselier explains, "Then I was dispatched to San Augustine County because of the sensitive nature of the debris."

"During the early hours, volunteer GPS teams began to assemble," says Williams. "FRI and HUES began to coordinate their data collection strategies. By midday, volunteer GPS crews were being dispatched with law enforcement, emergency personnel, and radio operators in response to the 911 calls to record precise locations and collect descriptive data on each debris find. During this time, the HUES staff agreed to coordinate and process GPS data collection while FRI staff agreed to develop and produce map products."

"The entire first response effort was phenomenal," states Williams. "Those who understand the utility of geospatial technologies began to show up at FRI and HUES during the first few hours without being asked and without being called. People wanted to go where there was equipment and where they could help."

The Annual Texas GIS Forum, the state GIS user conference, was to begin on day three after the disaster. FRI staff had planned to attend and present papers but obviously could not. Instead, they set up an audio link to the conference during the plenary session in which they gave a first-hand account to several hundred Texas GIS professionals. About an hour and a half later, a videoconference with the session was set up. Williams explains, "I can remember seeing friends on the video conference and saying 'come now-we need you!'" These were friends, geospatial professionals, who had the field science experience necessary for dealing with the dense forestry in eastern Texas and also the GIS and remote sensing technical expertise. And they came.

"We had volunteers from all over the state and the nation," states Blackwell. "These were people who left their businesses and families for 10-14 days on a voluntary basis to aid in the search and recovery effort. During the emergency period, our two labs saw a tremendous effort on the part of more than 200 geospatial people from all levels of responsibility-from students to top agency administrators."

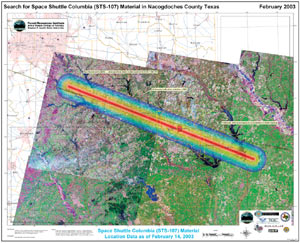

February 14, 2003, map of debris scatter in Texas and Louisiana. (Map courtesy of Forest Resources Institute. Images courtesy of USGS AmericanView Program. Vector data courtesy of Texas Natural Resources Information Systems.) |

|

Mike Parma, an employee from the city of San Antonio, came for a day and ended up staying another nine. He slept on Blackwell's living room floor, along with another dozen or so volunteers. His parents came to Nacogdoches to feed everyone dinner and restock the refrigerator. There were people who came to simply remind the volunteers to eat. Local church groups were cooking full meals, setting up boot drying racks for the field crew, bringing clothes, and doing their laundry. A kindergarten teacher volunteered to clean latrines after work.

"It was very chaotic during those early days. We were scrambling for computer equipment and chairs," says Williams. "People were camping in and around the building. Susan Henderson, former research associate at FRI, cooked breakfast for 80 people in a small downstairs kitchen. Every single electric plug in the building had some sort of battery charger, data collector, etc. Multiple power strips were used at each outlet. The HUES lab did a marvelous job setting up data dictionaries for the GPS data collectors so we could standardize."

GPS data was coming back from the field and added to the database. Around 2:00 p.m. on day one, the data set grew, and it became evident that there was a linear trend. The team began receiving GPS data from adjoining counties and saw the linear trend extending. It appeared to be accurate and consistent. Around this time Williams was feeling anxious, expecting ground injury and fatality calls to start arriving. "It didn't seem conceivable that no one on the ground got hurt, and I was hesitant to explore the spatial pattern. Miraculously, there were no ground injuries."

Blackwell explains, "I was concerned with the validity of the trend path because it followed Highway 21 and could have represented a population path. Also, I was suspect that the debris path was not as narrowly defined as our analysis was indicating. When we presented these first findings, we did it with many caveats. It turned out to be highly accurate, within 1-2 km on either end from Dallas to Toledo Bend on the Louisiana state border. This is an incredible illustration of the importance of geospatial technology."

Williams states, "We were running a simple least squares linear regression analysis against the relative location of reported debris to quickly see the scatter trend. When I displayed the regression in ArcInfo, it showed a linear trend with a bearing of 109 degrees relative to the shuttle reentry flight path. This Base Search Vector (BSV) model represented a best fit of data showing the debris trend. To display the magnitude of the debris scatter from the BSV centerline, I developed a 20-kilometer radial buffer with rainbow coloring signifying debris density. The first maps to incorporate the BSV encompassed only Nacogdoches County and were delivered to EOC by 4:00 p.m."

Blackwell continues, "NASA, of course, did much more sophisticated calculations later, considering velocity and weight, etc. What we did was 'down and dirty' hands-on analysis to get a job done immediately, and it worked."

HUES continued to process incoming GPS data, and FRI staff quickly added it to its maps. This continued throughout the night and into the morning. Sometime around daylight, using ArcInfo, Williams began to produce the first map that was presented to the international media in the afternoon of the second day. Approximately two dozen maps had been delivered to incident commanders at EOC by midmorning.

"The days after became a blur," according to Williams. "We typically began our day around 4:00 a.m., preparing maps for the EOC search and recovery teams by 7:00 a.m. Using ArcInfo and ERDAS IMAGINE, we began a daily process of map composition, data mining, data processing, and spatial analysis. It would then remain relatively quiet until the search teams returned after dark with their GPS data. Spatial analysis would extend into the early hours of the next morning."

FRI produced image-based operational maps for field navigation, strategic maps to aid the planning process for search and recovery efforts, and overview maps for the media. During the 14 days of FRI's involvement in the search and recovery mission, Williams mapped for more than 250 hours. He only slept two hours during the first 50 hours of the emergency. He was not alone.

"This is a very good case study for emergency response to a large-scale event using geospatial technologies," says Blackwell. "Nacogdoches County is located in a rural and forested part of Texas. Because of the expertise surrounding the university and the volunteer force from all over, we were able to respond in a dramatic way. This situation is a great example of the potential for small communities to deal with big things."

For more information on search and recovery of the Space Shuttle Columbia and geospatial first response efforts in Nacogdoches County, Texas, visit the Forest Resources Institute on the Web (fri.sfasu.edu) or contact Jeffrey M. Williams, GIS systems administrator (e-mail: jmwilliams@sfasu.edu), or P.R. Blackwell, information scientist, FRI (e-mail: prblackwell@sfasu.edu). Gregg Fuselier can also be reached at FRI (e-mail: gfuselier@sfasu.edu).

Visit the Arthur Temple College of Forestry on the Web (www.sfasu.edu/forestry). Also visit the HUES lab on the Web (strand.sfasu.edu).

For more information on spatial solutions, contact Leica Geosystems (tel.: toll free in the United States at 1-877-463-7327 or outside the United States at 1-404-248-9000, Web: (gis.leica-geosystems.com).

|