Lawless litterers, beware!

New Jersey citizen volunteers now can use a new GIS-based crowdsourcing web app to report and map cases of illegal dumping throughout the state.

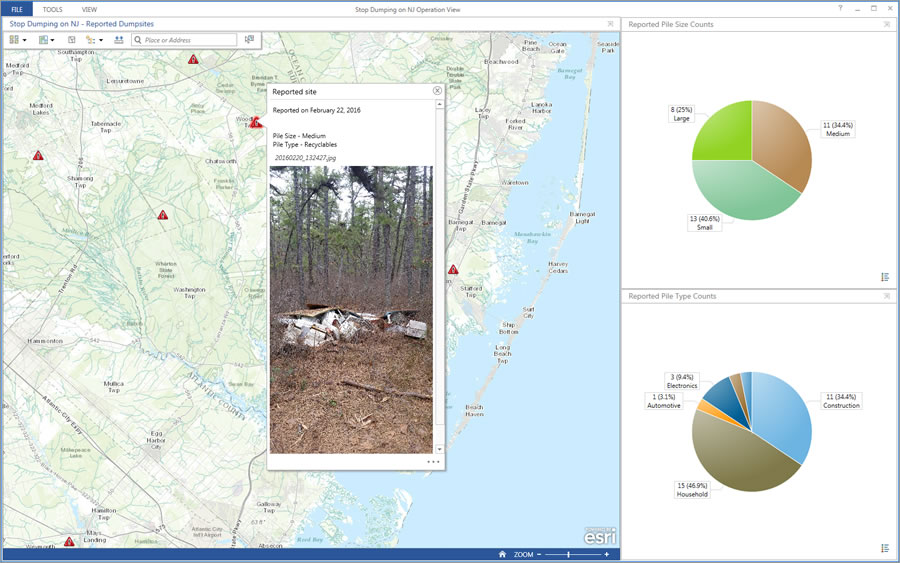

The app, created by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) using Esri ArcGIS technology, lets people specify the type of debris dumped, such as construction or hazardous materials, and the size of the pile, such as small, medium, or large. They can use their smartphone to take a picture of the debris and upload the photo via the app. They can then use their device’s GPS to capture the debris location and add the information to a map.

DEP staff can view the crowdsourced reports in Esri’s ArcGIS Online.

“Because volunteers are using the GIS web app to report illegal dump sites, we can understand what’s happening,” said Arthur Zanfini, administrative analyst with Compliance and Enforcement for DEP. “We can see the reports on a map along with truck routes, transfer stations, or recycling centers. Then we can easily see correlations between dump site locations—that clue us in to what is happening.”

DEP hosts the app, which is accessed through web browsers on mobile devices.

Sprucing Up New Jersey

DEP has a long history of using innovative ideas to keep the state clean. The department launched the Don’t Waste Our Open Space campaign to reduce illegal dumping in state parks and wildlife management areas. GIS is a driving technology for this initiative.

Each spring, thousands of people gather to clean up litter during the Barnegat Bay Blitz, held in Barnegat Light, on the Jersey Shore. Since 2011, local volunteers have been turning out to participate in the one-day event, sponsored by the DEP. From the start, the magnanimous community was truly engaged in this worthy cause. Unfortunately, volunteers soon realized that their efforts were being undermined and that they were cleaning up the same sites year after year. Wanton waste disposers had been returning to the scenes of their crimes, dumping garbage onto the once pristine landscape. It was time to make a stand.

The Don’t Waste Our Open Space campaign task force is composed of conservation officers and representatives from numerous DEP agencies including Compliance and Enforcement, Water Resources Management, the state parks service and police, conservation officers, New Jersey Natural Lands Trust, and DEP’s Bureau of GIS (BGIS). The group’s objective is to curtail illegal dumping by incorporating strict enforcement of the law while raising the public’s awareness of the dumping problem.

“We had people from the department sit down at a table and figure out a strategic way to work with what we have to attack a problem in our state,” said Zanfini. “We leveraged the Esri platform to aid in our effort.”

For decades, the DEP has been using Esri products, including an enterprise platform that is essential for sharing responders’ data about environmentally sensitive areas. With the platform already in place, it was natural and cost-effective for the task force to rely on it as a core technology for encouraging public participation in the project, changing people’s perceptions about dumping laws’ enforcement, and catching offenders.

Engaging Citizens

Public lands throughout New Jersey have become dumping grounds for perpetrators that unload litter, garbage bags, tires, televisions, electronics and appliances, yard waste, and construction debris. Illegal dumping threatens the local environment, wildlife, and the public. Moreover, it detracts from the natural beauty of public land, decreases property values, and costs the citizens of New Jersey tax dollars for cleanups.

The banner on the DEP’s Stop Illegal Dumping website reads, “Don’t Walk By While Your Park Is Trashed.” On that same website, citizens access a crowdsourcing app that enables them to take action by taking geotagged photos at illicit dump locations. People can send these images to the DEP along with incident information that they enter into a form on the app.

At each state park, DEP displays posters about dumping laws and their enforcement. These posters include a QR Code linked to the informative Don’t Waste Our Open Space landing page. The website tells visitors how to report illegal dumping to the DEP via the GIS web app on their smartphones’ browsers. App users can also use their cell phones to call a 24-hour hotline and make a report. GIS tracks the reports’ coordinates and posts them on a map so that investigators know exactly where to find evidence.

Catching Offenders

Citizens use the crowdsourcing app to report incidents such as dumped trash bags, leaking tanks, or dumpsters that contain asbestos shingles. Having photos and GPS coordinates helps authorities respond quickly.

When a user clicks the Submit button, an automated workflow begins. The app writes reports and photos to a feature service. At five-minute intervals, a Windows task runs a Python script that checks the feature class for any new entries that may have been submitted. The GIS processes spatial filter procedures that categorize location reports as being within the New Jersey boundary, a state park, or a municipality. GIS also notes if other illegal dump sites have been reported within 500 feet during the last two weeks, which may indicate a duplicate submission.

The web app report triggers an alert that lets DEP staff know about an alleged case of illegal dumping. If the incident is within a state park or wildlife management area, the report goes to the DEP’s communications center for investigation. Staff sends an email alert to the appropriate authorities for follow-up. If the email is sent to a park police department, the incident is automatically logged in the department’s dispatch system.

The ArcGIS Online map shows the reported locations of illegal dumping, along with the date of the report, so that investigators can analyze relationships and patterns. The image shows the magnitude of the incident so that staff can prioritize responses. Photos show items at the dump site, which may reveal whether the materials come from a nearby facility. Maps provide more context, such as the number of reports generated along a section of railroad track or a truck route.

Changing Perceptions

In a preproject survey, DEP discovered that most New Jersey residents did not believe that the state enforces its own dumping laws. The task force knew that its mission would not be successful if it had to rely on its small number of enforcement officers to decrease dumping on more than 814,000 acres of state land. The task force had to be smart. To deter potential perpetrators, it had to change the community’s perception and prove that laws are enforced and polluters are prosecuted.

To convey the message, the team published an online, interactive story map. It shows pictures of offenders that have been caught and the maximum fines they could face for their specified offenses. The Esri Story Maps app templates let DEP easily update photos and information for their story map.

Measuring Success

You can’t tell whether a program is working if you don’t measure results. From the inception of the project, the DEP task force set up progress indicators and established baselines for comparisons. For example, the results of the initial public survey provide a baseline for measuring the program’s ability to change the public perception that laws are not enforced. Perceptions can be measured over time. Another progress indicator is the number of reports made by recreational hikers and other park visitors and submitted via the web app.

Mapping the number and locations of arrests for illegal dumping over time makes it easier to understand data about law enforcement success. Furthermore, analysts can determine which arrests were related to citizen reporting. This year, mapping data from the Barnegat Bay Blitz cleanup day will show if and where volunteers are finding less trash in previously hard-hit areas, showing whether dumping activity has decreased. This is also a good way to advertise the effectiveness of the event.

It will take DEP a few years to gather measurements that show exactly how successful the Don’t Waste Our Open Space program has been. Within the first few months of its trial launch, volunteers had already started using the app.

Locating More Opportunities

Crowdsourcing apps are helping citizens participate in other action-oriented projects. For example, the DEP created a reporting app that members of the AmeriCorps NJ Watershed Ambassadors Program use to collect and report stream data necessary for keeping waterways clean. Moreover, community volunteers use a DEP web application to verify the locations of public access to the New Jersey coastline. Their work contributes to a map that shows where the shore is open to everyone.

Zanfini is happy to spread the word about the GIS solution for illegal dumping and to talk with other agencies interested in implementing a similar project. Contact him at Arthur.Zanfini@dep.nj.gov.