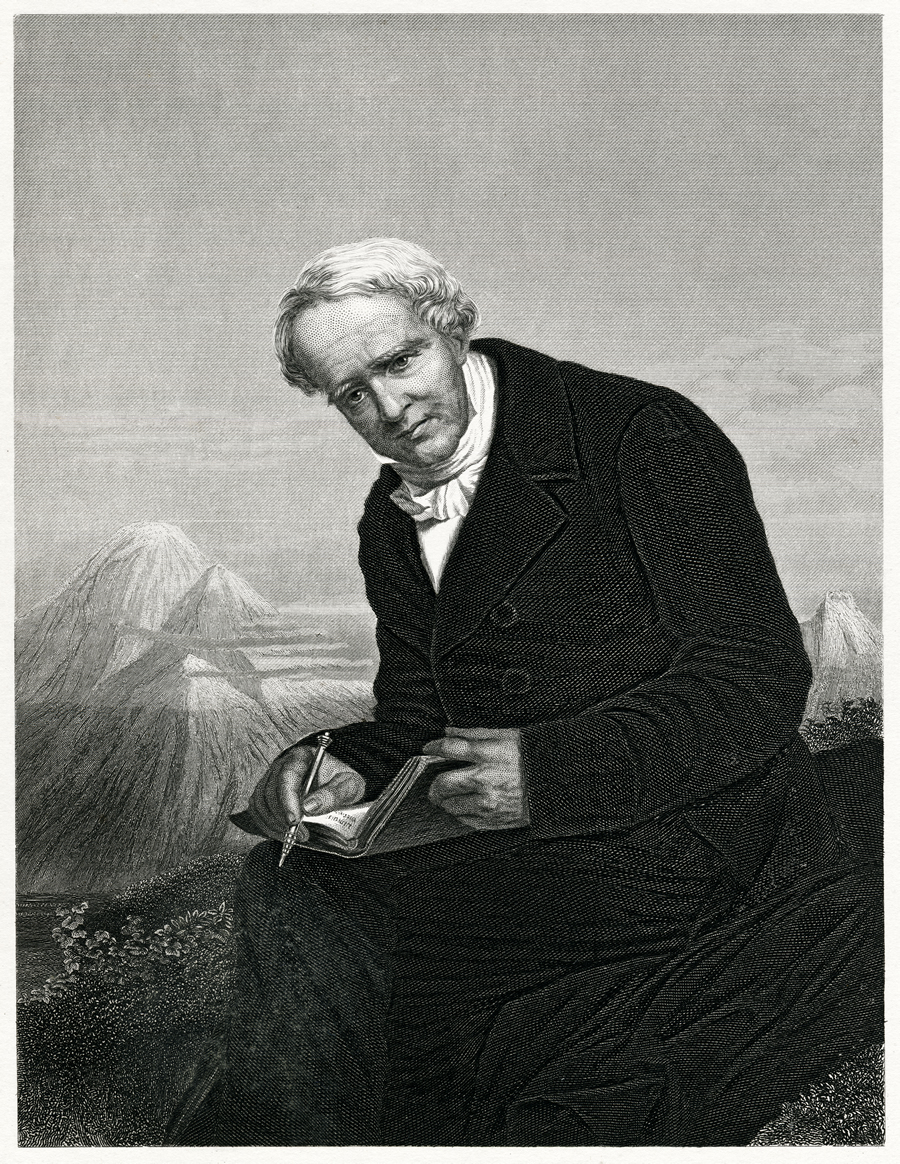

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, Alexander von Humboldt was the embodiment of a Renaissance man. A famous expedition to the Americas had the Prussian explorer, geographer, and naturalist climbing steep, icy Mount Chimborazo, an inactive stratovolcano in today’s Ecuador; battling oppressive heat, rain, and mosquito hordes while trying to steer clear of crocodiles during a trip down the Orinoco, one of South America’s longest rivers; and meeting president Thomas Jefferson and future president James Madison, two American Founding Fathers.

Perhaps you’ve never heard of Humboldt. Andrea Wulf, who wrote a book about his life called The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World, doubts you have. But she hopes you will come to know and appreciate him as the world once did.

Esri president Jack Dangermond gave The Invention of Nature a rave review. “I read her book, and it was amazing,” he told the audience at the 2016 Esri User Conference (Esri UC) Plenary Session in San Diego, California, where Wulf was the keynote speaker. “She channeled one of the greatest scientists of our time—well, not our time—a previous time.”

Wulf extensively researched Humboldt and his writings, including his five-volume scientific crown jewel, Cosmos: A Sketch of the Physical Description of the Universe. She credits him for first raising the alarm about human-caused climate change, being a pioneering force in the fields of infographics and mapmaking, and bringing the arts and sciences together to understand nature.

“Humboldt invented a concept of nature that still very much shapes our thinking today. He came up with this idea that nature is a web of life,” she said. “He described the earth as a living organism where everything was connected, from the tiniest insect to the tallest tree.

Famous Name, Forgotten Man

Maybe you’ve heard of the Humboldt penguin; the Humboldt Current; the Humboldt squid; Humboldt’s lily; Humboldt County, California; or, perhaps, even Humboldt, Saskatchewan. Though many places and things bear Humboldt’s name in honor of his scientific observations and explorations, his story languished in relative obscurity for years until Wulf published The Invention of Nature, named by the New York Times as one of the 10 Best Books of the Year in 2015.

Wulf said Humboldt was “brazenly adventurous—not a cerebral scholar,” a man considered the “greatest and most famous scientist of his age.” Essentially forgotten over time except by a small circle of scientists, geographers, and naturalists, Wulf said her goal is to return him to his rightful place in the pantheon of science.

Wulf described him as a restless man. “Humboldt was a scientist who believed you can’t sit in your study and learn from books,” she said. “You have to go out and see the world. And it shaped his view of nature.”

Humboldt had an insatiable thirst for knowledge about nature. He was fascinated by everything from fluttering butterflies to rumbling volcanoes. He was famous for his far-flung explorations and scientific observations, which led him, as Wulf writes, to view nature “as a global force.”

Humboldt witnessed this interconnected ecosystem as he journeyed through South America from 1799 to 1804, lugging 42 instruments, such as barometers, thermometers, and cyanometers, which he used to study the environment.

Born in Berlin, the intrepid explorer noticed signs of human-caused climate change, Wulf said. He warned of trouble after a visit to Lake Valencia in present-day Venezuela and saw that the land surrounding the lake was barren, having been cleared of trees for plantations that grew cash crops like indigo, sugar, and tobacco. “Forests had been felled. Heavy rain was washing off top soil. The lake level was falling and [farmers were] diverting water to irrigate fields,” Wulf said during an interview from her home in London, England, prior to the Esri UC.

Humboldt noticed other ways that humans were negatively altering the ecosystem—for instance, depleting the ocean’s oyster stocks from overfishing and damaging the land from mining operations. “He saw nature as a web of life,” Wulf said. “If you pull one thread, the whole thing might unravel.”

Before GIS, There Was Naturgemälde

The Invention of Nature describes in detail Humboldt’s quest through South America, where he mapped rivers, collected plant samples, studied rocks (he was a trained mining inspector and geologist), and even conducted experiments on electric eels.

Following a 19,413-foot climb up Mount Chimborazo that left him bloodied and ill, he took all his measurements, such as altitude, air temperature, and barometric pressure, at various locations, along with extensive notes on the locations of plants and animals, and began to initially sketch his Naturgemälde, which in English loosely translates to “painting of nature.”

Wulf said that after Humboldt returned to Europe, he hired mappers and artists to create a color lithograph of the Naturgemälde. Geographie der Pflanzen in den Tropen-Ländern or Geography of Plants in the Tropical Countries, was published in the 1807 Essay on the Geography of Plants by Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland, the French botanist who accompanied him to South America.

Snow-covered Mount Chimborazo appears in the lithograph, with a small plume of ash spewing out the top. Written into the mountainside are the names of plants, mapped at the location where Humboldt and Bonpland found them. Columns on the left and right sides of the lithograph contain information including the elevation, barometric pressure, temperature, types of soil, blueness of the sky, and the boiling temperature of water at various elevations. One column contains extensive notes on the men’s geognostic view of the tropical world.

The lithograph of the Naturgemälde with its mapped plants looks like an early version of a geographic information system (GIS), and Wulf concurs. “That is exactly what it is,” she said. “It is packed with complex information, yet it is simple to understand. It shows connections that no one knew before.”

Everyone who attended the Esri UC Plenary Session received a copy of the lithograph in poster form.

Humboldt used infographics to show the spatial distribution of the plants on the mountain and the relationship between the types of vegetation found at various elevations. Publishing the lithograph in a book was his way of sharing that knowledge with a wide audience.

“He so much believed that knowledge should be accessible to everybody,” Wulf said. “He is similar to the GIS community. He believes in a free exchange of information [like what is done today] through Web GIS.”

Long after she had sifted through dusty archives, reading the writings of Humboldt and his admirers including Charles Darwin and John Muir, long after she had followed in his footsteps up Mount Chimborazo, and long after she had written The Invention of Nature, Wulf arrived at Esri headquarters in Redlands, California, last April to speak about her book and learn more about GIS. She was impressed with the creation of the Living Atlas of the World, led by Esri, which includes contributions of maps, apps, and imagery from many organizations.

She said Humboldt was a big believer in collaboration and of making knowledge accessible. “Humboldt created an incredible network of people who helped him collect all this information, and that’s what you are doing when you are engaging with citizens, students, scientists, [and] coworkers,” Wulf said. “You have contributed millions of datasets—it’s a Living Atlas that Humboldt could have only dreamt of.”

Wulf said she felt quite at home at Esri. “When I went to Esri, I thought I’d landed in a Humboldtian heartland.”

Wulf believes Humboldt would feel right at home, too, at the Esri UC. “I am pretty sure he would have loved this community, and he would have loved the possibilities of GIS, because what you do here is truly Humboldtian.”

Esri UC attendees, such as Judith Bock from Elmhurst College in Illinois, were delighted by Wulf’s talk. “Her passion about him came through, and I learned a lot about him,” Bock said, adding that the information Wulf provided about Humboldt’s Mount Chimborazo vegetation map was particularly enlightening.

Noel Cressie, an expert in spatial and spatiotemporal statistics and a distinguished professor and director of the Centre for Environmental Informatics at the University of Wollongong in Australia, was equally impressed by this year’s keynote. “I thought it was wonderful to hear about Humboldt, a scientist for all of science,” Cressie said. “He was probably the last scientist who saw the big picture.”

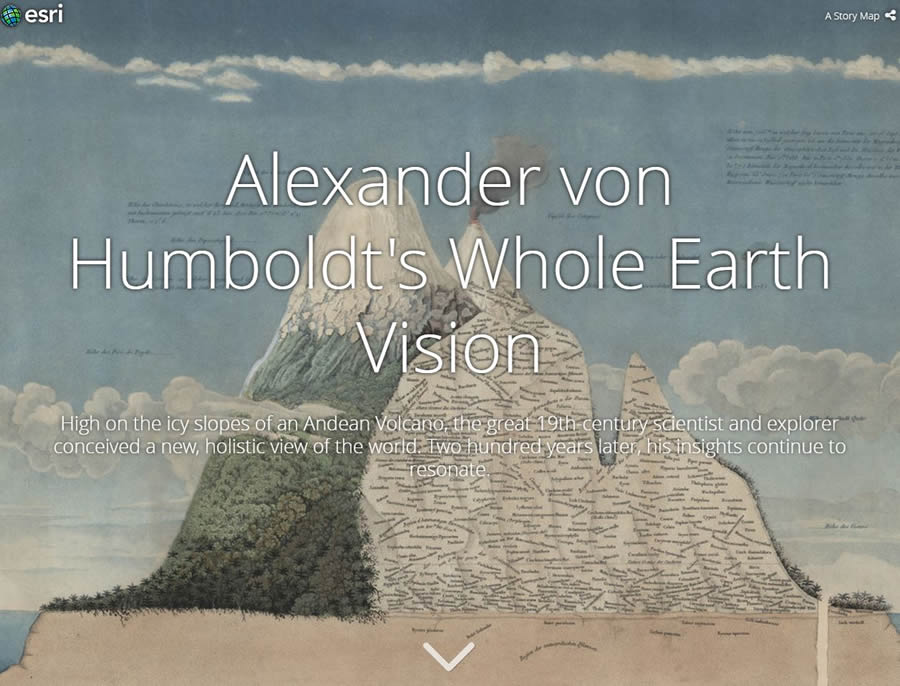

Watch Wulf’s presentation on video. View the Esri Story Map Alexander von Humboldt’s Whole Earth Vision to learn more about the scientist’s expeditions, studies, and lasting legacy.