The collared peccary of Ecuador and the black-backed jackal in Kenya act differently in their natural habitats than in a zoo. You can see how they interact with other animals and how they hunt for food at Smithsonian WILD, a website filled with images of animals photographed in the wild. Maps powered by Esri show where those photos were taken, too.

For this Smithsonian Institution project, researchers use motion-triggered camera traps to capture the animals’ images. The small, ruggedized camouflaged cameras are waterproof, have multiple sensors, and can be locked. They are attached to trees or other natural objects. The camera’s infrared recognition sensor detects animals at night and trips the camera, which takes rapid-fire pictures.

Wildlife from all over the world were captured on camera including bears, coyotes, foxes, lions, deer, pigs, zebras, iguanas, owls, and many others. More than 206,000 photos of animals are now online, along with the accompanying Esri powered maps that show their habitats and where they were photographed.

The Smithsonian Institution worked with Blue Raster, LLC, to build an application that accesses Esri ArcGIS Online basemaps and images that are stored on Flickr and include the x,y coordinates of camera locations. This makes it easy for users to search for animal photos, descriptions, and locations by entering a name, selecting an option, or clicking an area or camera site on a GIS map.

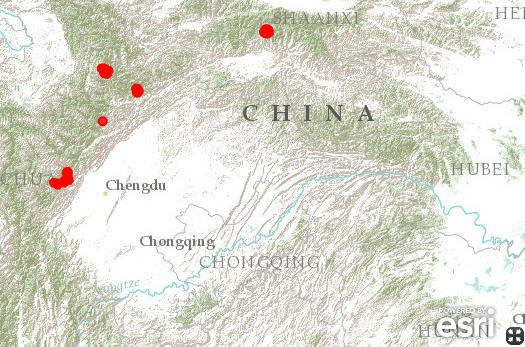

Search the index of animals for the golden snub-nosed monkey, for example. A map on the web page shows the primate’s habitat in central China. If you zoom in on the map, you will also see images of other animals in the area such as the barking deer, leopard cat, and giant panda (more about the pandas later).

“GIS takes the viewer from a bird’s-eye view of the region and drills down to the camera location on the ground where these animals are recorded in space and time,” said Robert Costello, national outreach program manager for the Smithsonian. “Each image is like a museum specimen in a sense. The photo is a voucher for the existence of that species at that place and time. It is a record with the potential of becoming more important over decades.”

The Smithsonian WILD website includes a red taskbar that makes it easy for the user to select a species and learn about a project. You can click the A–Z Index of Animals tab and select from a category (e.g., bears). You can click on a species by name; both its common name, such as giant panda, and its scientific name (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) are shown. The giant panda web page includes links to species source data from the Encyclopedia of Life and the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List databases.

Caught in the (Camera) Trap

The web application also has thumbnails of panda photos taken by camera traps. Click a photo and it links to a page with project information and an Esri-powered map. Click the map and zoom to panda habitats in Sichuan, China, where the camera traps are located. These camera points link to an album of all species photographed by that camera. The user learns about the giant panda; its behavior; and other creatures that share its habitat, such as the Chinese serow.

When the site launched in 2011, popular media sources such as Wiredmagazine, Gizmodo, Engadget, and NBC Nightly News, quickly picked up the story. Smithsonian WILD has had as many as 57,000 visits in a single day. It is a cloud-based website with tools that access Esri’s map services (basemaps) from ArcGIS Online. The project’s images are managed on Flickr. After paying nominal fees for a Flickr Pro account and use of the Amazon cloud, Blue Raster quickly moved the Smithsonian’s 206,000 images to the Flickr platform.

A Mobile Guide

Will such a species information service replace the trusty field guide? Possibly. The common field guide is comparatively inaccurate, because it shows gross estimates of the potential boundaries of a species.

Smithsonian WILD shows the locations where the species were actually seen on camera. A field guide provides one map for one species at a time, but Smithsonian WILD shows the community of species that are active at a geographic location. A field guide is easily stuffed into a rucksack. Smithsonian WILD can also be stuffed into a rucksack.

In 2012, Blue Raster built a mobile application that works on iOS (iPhone and iPad) and Android phones and tablets and accesses Smithsonian WILD maps via ArcGIS Online. One might expect that two development teams would be needed to build the smartphone application—one familiar with Objective-C for iOS and the other with the Android language.

However, Blue Raster wrote the application once by using ArcGIS API for Flex to create the application and Adobe Flash Builder to compile it into formats that run on Apple iOS and Android devices.

Users can analyze animal activity and behaviors in ways that were never before possible. Scientists and others can see how the animals act and interact in near real time.