If you drive north on Idaho Avenue North in Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, and go about a block past 71st Avenue, you will spot a red fire hydrant on the left side of the street. But it’s not just an ordinary fire hydrant. It’s Squirt, named by Brian, the man who adopted the hydrant using the city’s new online Adopt a Hydrant mapping app.

Brian assumed responsibility for Squirt, promising the Brooklyn Park Fire Department that he would keep the hydrant clear of snow and ice during what’s likely to be a long, cold, snowy Minnesota winter. The agreement is informal and nonbinding—Brian could abandon Squirt simply by clicking his mouse on the Abandon Me link. But city GIS coordinator John Nerge said that rarely happens in the civic-minded city of 78,728 people, located 10 miles northwest of Minneapolis, unless someone moves.

The City of Brooklyn Park’s Operations and Maintenance Department is tasked with clearing snow from the hydrants. Being able to easily access water quickly during a fire can be a matter of life and death. “Extra seconds matter in saving a property or a life,” Nerge said.

Hydrants covered by snow or surrounded by high snowdrifts or banks give firefighters a big headache, sending them scrambling—possibly in the dark—to clear a pathway to the hydrant and then shovel the snow off of it. Because it’s difficult to quickly remove snow from all 3,500 hydrants following a winter storm, fire officials sought out the public’s help by developing a civic engagement app that encourages hydrant adoption. “The goal of this program is mainly to help us save lives,” said Stephanie Pemberton, a program assistant for the Brooklyn Park Fire Department.

A Fun and Family-Friendly App

With this in mind, Pemberton pursued the idea of an Adopt a Hydrant program for Brooklyn Park. While other cities around the country have them, she thought hosting a mapping app would provide a great way to engage more people in the idea of personally caring for hydrants. “Some people are shoveling without officially adopting on the app, but we thought this was a new way to cause interest and engagement in a day and age of apps and tech,” Pemberton said.

She did some research online and learned about the City of Boston’s Adopt a Hydrant mapping app, created by Code for America, and found the code for the app in the GitHub repository. The app was created using the Ruby on Rails framework with a Postgres database.

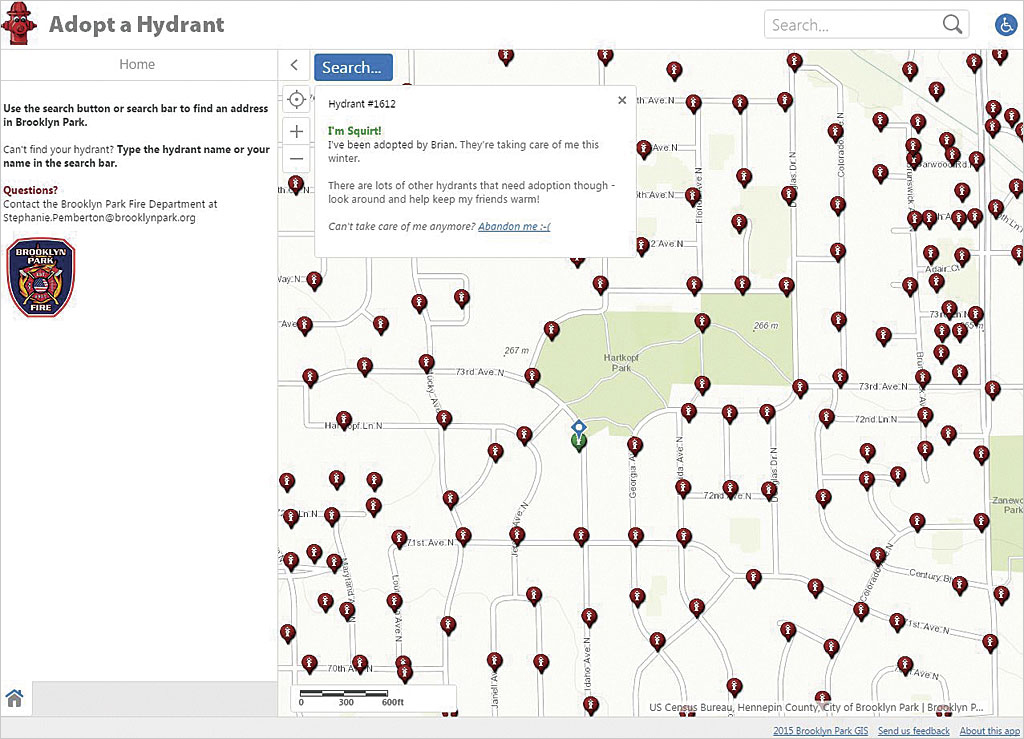

When contacted by Pemberton, Nerge, (an unapologetic nondeveloper) said he decided to use the software and services he had available instead—Geocortex Essentials and ArcGIS for Server. Nerge supervised Kaela Dickens, a GIS intern in Nerge’s office, who used Geocortex Essentials software to create the customer workflows and app components. These componenets included the text introducing the app to users; the address search box; the hydrant symbols; the adopted hydrant’s back story including its name; other search tools to find and select a hydrant; the Adopt me! links; the form that collects people’s names, email addresses, and hydrant names; and everything else the user or administrator needs to interact with in the app.

The online map, an HTML5 app built using Geocortex Essentials software from Esri partner Latitude Geographics, uses basemaps and transportation layers from ArcGIS Online and runs on Esri’s ArcGIS for Server. An ArcGIS for Server service records and stores information on hydrant adopters.

The app is user-friendly. People just open the app in a web browser, type their home or work address in a search box, and click Find Address, and the map automatically zooms to the location. As users zoom out from the address, the hydrants available to adopt appear as red icons. Fire hydrant icons that are green have already been adopted, while those pending adoption are yellow.

Each red hydrant on the map has a number and a pop-up that displays a message that reads “Hi, I’m available for adoption,” and a blue link saying “Adopt me!” That link takes people to a form that asks for their name, email address, and a name for the hydrant.

The app was designed to be family friendly. Dickens, who has served as an intern for Brooklyn Park for a year and a half while she earns a master’s degree in public policy at a local university, wanted the app to have lighthearted tone. She used simple language in the text of the pop-ups to appeal to parents who have small children and might be interested in adopting a hydrant.

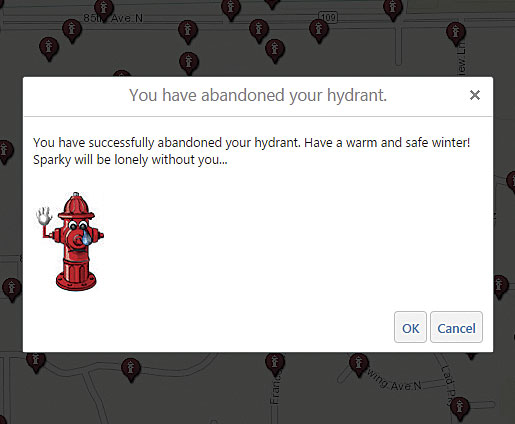

She wrote a standard reply for each hydrant. For example, hydrant #36 (also known as Sparky) generated this message when it was adopted: “I’ve been adopted by Hoidal. They’re taking care of me this winter. There are lots of other hydrants that need adoption though—look around and help keep my friends warm! Can’t take care of me anymore? Abandon me.”

If Sparky the Hydrant is abandoned, Hoidal will receive this automatic message generated by the app: “You have successfully abandoned your hydrant. Have a warm and safe winter! Sparky will be lonely without you.” A cartoon drawing of Sparky waving good-bye with a tear coming out of his eye is included.

“It seems people are having fun with it,” Nerge said. “That was the hope.” Joining Squirt and Sparky on the front line of the fire department’s army of hydrants are Viper, Batman, Captain Maximus, Diego, Olaf the Snow Hydrant, Miss Scarlett, Inigo Montoya, The Little Hydrant that Could, and Joe’s Flow (adopted, of course, by a guy named Joe).

Pemberton uses an administrator version of the app to send out confirmation emails when adoptions have been approved (or rejected, if the proposed hydrant name is deemed racy or offensive). She also will notify hydrant adopters if snow is forecast for the Twin Cities, gently reminding people to remove snow from the hydrants soon afterward. She personalizes the messages, too, writing questions such as, “How did Spot do in the snowstorm?” or comments such as, “I hope Olaf is keeping warm.”

Working with Residents

Adopt a Hydrant, one of the apps in the city’s gallery of 31 maps, offers a way for the city to communicate directly with residents. In the future, the staff hopes that the app and others like it will help get people involved with city government and foster civic engagement. “The motto at Brooklyn Park is, ‘We don’t do things to people. We want to do things with people,’ ” said Dickens.

Of the 3,500 hydrants in the city, about 45 have been adopted since the app’s launch last year, and that number is expected to climb this winter as a public awareness campaign goes into full swing. While the initial adoption numbers might seem like a drop in the bucket, even a budding program like this is valuable to firefighters, who depend on easy access to hydrants when fighting a fire. The city plans to build a mobile mapping app that includes the location of all the adopted hydrants, making it easier for firefighters to find ones they know will be cleared of snow.

“We’ve always had Good Samaritans shoveling out hydrants,” Nerge said of the residents. “This was an opportunity to create a program that would inspire neighborhood pride and be fun by naming the hydrants.”