The first Ocean GIS Forum

This year’s event, the first of what is expected to be many ocean GIS conferences, showcased the multitude of ways the ocean community uses GIS to better understand and protect the ocean. Speakers at the conference emphasized the importance of enlisting the public’s support in saving the world’s oceans from the adverse impacts of human activity. The event also gave Esri an opportunity to unveil new tools and enhancements to existing tools for handling multidimensional data.

The conference, held November 5–7, 2013, on the Esri campus in Redlands, California, drew 150 attendees from academic and research institutes, government agencies, nonprofit organizations, consulting firms, and ocean-related businesses that use GIS in the marine environment. While most were from the United States, some attendees traveled from Spain, the Russian Federation, Brazil, Canada, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom. The event was sponsored by Oceaneering, ExactEarth, QPS, Amazon Web Services, and RPS/ASA.

The groundwork for this event was laid last year at the first—and only—Esri Oceans Summit. Fifty leaders in the oceans community invited to the Redlands campus were joined by an almost equal number of Esri staff to establish a community of GIS ocean interests, identify challenges to using GIS in the ocean environment, and guide the development of GIS tools for that community.

The summit was one of the first steps outlined in the Esri Oceans Initiative. Announced in 2012, it is an organization-wide effort to enhance Esri’s capabilities to support GIS in both coastal and open ocean applications. Esri has been involved in ocean conservation efforts since it first developed a marine spill analysis system in 1989. Efforts in this area continued with digital nautical charting projects with National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) [former name of the US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency] and hydro information systems for Finland and Sweden. This work highlighted the need for handling more than two dimensions and resulted in the development of a data model for the marine environment.

Exploration and Understanding

Keynote speaker Dave Gallo, an oceanographer and the director of special projects at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, was one of the first scientists to use both robots and submarines to explore the deep sea floor. Recently, he has become more widely known for his work with the film director James Cameron and for his wildly popular Technology, Entertainment, Design (TED) Talks.

At the beginning of his address, Understanding Precedes Action, Gallo displayed an image of the earth as seen from space. It emphasized one of the challenges facing the ocean community: the misconception that “since we can see it all we know it all.” The reality is that only a small percentage of the ocean has been studied. But even that limited exploration has revealed the ocean as a place of vast diversity, esoteric creatures, and geological features that dwarf terrestrial mountains and valleys.

“Oceanography, to me, has always had these two parts. There is the excitement of exploration and discovery,” said Gallo. “The other part is the importance of understanding it for the sake of the planet.” Gallo has been using GIS as a tool for increasing his understanding since the 1980s when he traded his colored pencils in for ARC/INFO when drawing bathymetry contours.

He observed that the lack of a holistic view of the ocean is the underlying cause of the poor response to events like the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Years of studying the ocean have impressed on Gallo the critical importance of the ocean to everyone and the need for the public to support the work of the ocean community.

Enlisting the Public

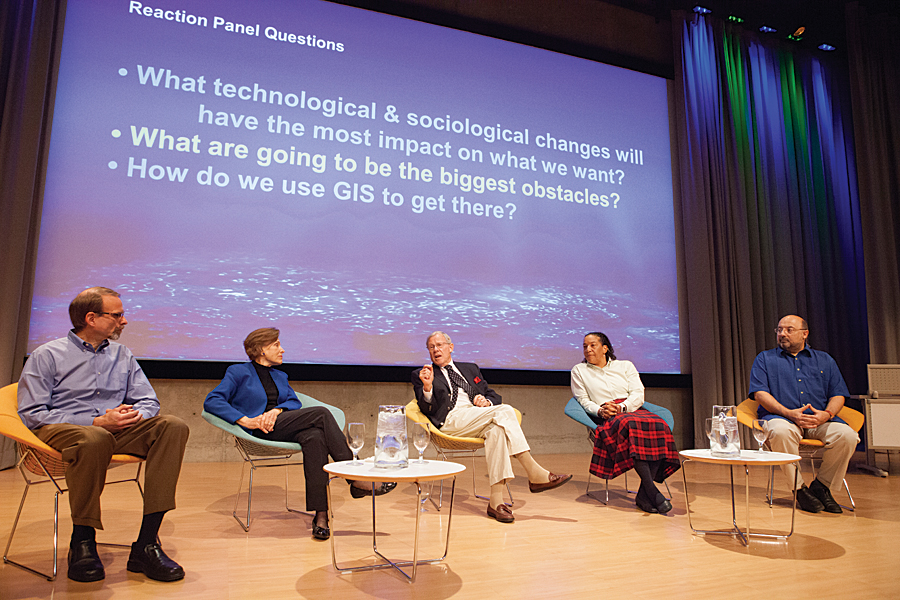

In the panel discussion that followed Gallo’s keynote, Sylvia Earle reenforced Gallo’s message that “protecting the blue part of the planet that keeps us alive” should be our first priority. Earle is a renowned oceanographer, author, and National Geographic explorer-in-residence. She was joined by Dr. Jerry Schubel, president and CEO of the Aquarium of the Pacific; David McKinnie, senior adviser for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Ocean Exploration Research; Gallo; and Wright.

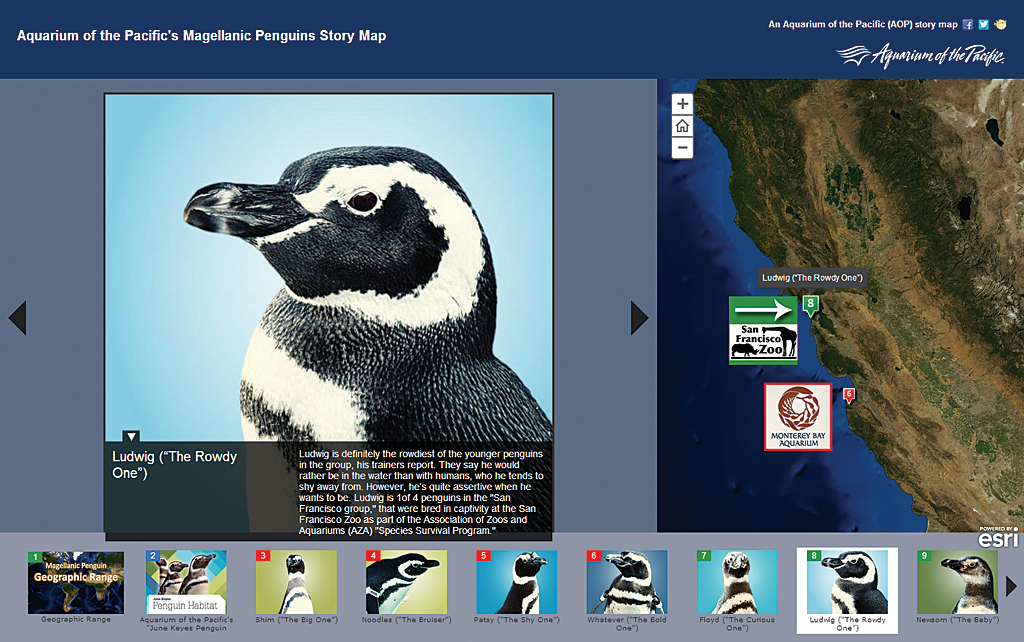

Schubel talked about the importance of getting “the public interested in, commited to, and caring about the ocean. You’re all involved with data but the public and the policy makers don’t want data,” he said. “They want information. Data has to be converted into information, and that is one of the powerful things that GIS can do.” GIS aids collaboration and helps the ocean community tell powerful stories to the public. Schubel’s Aquarium of the Pacific has effectively used story maps to translate science to the public.

Data sharing, public engagement, and technology were three of the major components of a national program for exploring the ocean discussed at Ocean Exploration 20/20: A National Forum, held July 19–21, 2013, in Long Beach, California, at the Aquarium of the Pacific. McKinnie, in speaking about the 20/20 event, noted that the need for good data has contributed to a blurring of the line between exploration and research with the advent of privately funded researchers and citizen explorers. This means more data users and more data providers, resulting in more data but also a more complex landscape that requires some agreement on priorities, partnerships, platforms, and technology development.

Pushing the Limits of GIS

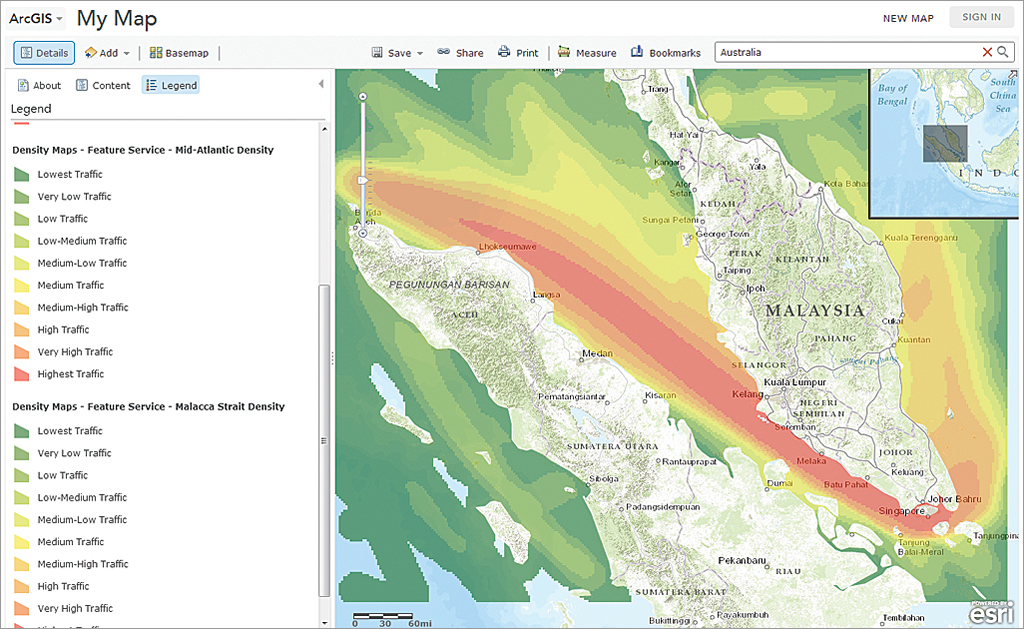

During the afternoon on both days, Lightning Talks by an assortment of researchers, people in marine-related businesses, and government agencies gave a quick overview of the many ways the ocean community is exploiting the latest GIS capabilities for collecting, managing, and analyzing large, complex datasets and collaborating and communicating using web mapping and the ArcGIS Online platform.

One of the Lightning Talks given on the first day aptly illustrated how GIS is enabling crowdsourced ocean science. Lei Lani Stelle, an associate professor of biology at the University of Redlands in California, described a smartphone app that helps gather data on marine mammal sightings. She maps mammal distributions to identify and find ways to mitigate potential human-marine mammal conflicts.

The app lets her obtain data in a usable format from a previously untapped source: companies that offer whale watching tours. The app uses the device’s GPS capabilites to supply location information, user accounts qualify who is submitting the data, and drop-down selections in the interface speed the input of species and activity information. A photo can also be included. Observations are uploaded by syncing to an online geodatabase.

Another presentation demonstrated how GIS is helping oil and gas companies operate in the marine environment more safely. In just five minutes, Mark Stevens described how GIS helps his company, Oceaneering, provide a common operationing platform (COP) for intelligently and rapidly responding to incidents and disaster and coordinating drills. Oceaneering, a sponsor of the Ocean GIS Forum, supplies engineered services and products to the offshore oil and gas industry and specializes in deepwater applications.

The company creates COP interfaces for clients that use ArcGIS Online to create mapcentric, GIS-based dashboards that integrate information about a site with all types of data on current conditions and operations including the deployment of vessels, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), other special equipment, and staff. Oceaneering works with companies to define and prebuild bathymetry, environmental, and other layers that support a COP and inform response efforts.

Improved Tools for Ocean GIS

The second day began with the technical plenary session delivered by Kevin Butler, a member of the Esri product development team. He demonstrated how the ArcGIS platform can serve as a basis for e-science and highlighted ongoing development efforts to improve support for multidimensional scientific data—specifically support for Network Common Data Form (netCDF), GRIdded Binary (GRIB), and Hierarchical Data Format (HDF) data in the mosaic dataset and rendering rasters as vector fields. This work was inspired by feedback gathered at the Ocean Summit last year.

Many of these development efforts have been delivered in the Multidimension Supplemental toolbox Version 1.1, a collection of nine tools that extend the functionality of the Multidimension toolbox. The tools, developed in response to requests for better support of the OPeNDAP protocol and netCDF files, can be used as-is or modified to handle specific use cases. Additional tools, new with this version of the toolbox, perform statistical operations on multidimensional data. (Download this toolbox for free at esriurl.com/MultidimensionSupplementalTools. Note that the samples included are designed for ArcGIS 10.2 and higher.)

Existing GIS tools have also been enhanced with the capabilities requested at last year’s Ocean Summit. Mosaic dataset functionality has been expanded to allow the storage of netCDF data so that it can be temporally and spatially aggregated.

Esri software engineer Shaun Walbridge introduced a new version of the Benthic Terrain Modeler (BTM). This set of Python scripts in a custom toolbox lets ocean researchers extract more value from bathymetric data by classifying surficial seafloor characteristics for use in studying benthic habitat, geomorphology, the prediction of benthic fish species, and other aspects of oceanography. BTM can create grids of bathymetric position index (BPI), standardized BPIs, slope, and terrain ruggedness from an input bathymetric dataset. Two terrain classification tools let users create zone and structure classifications and define the relationships that characterize them. BTM is open source, and the code is available on GitHub.

More Data Resources

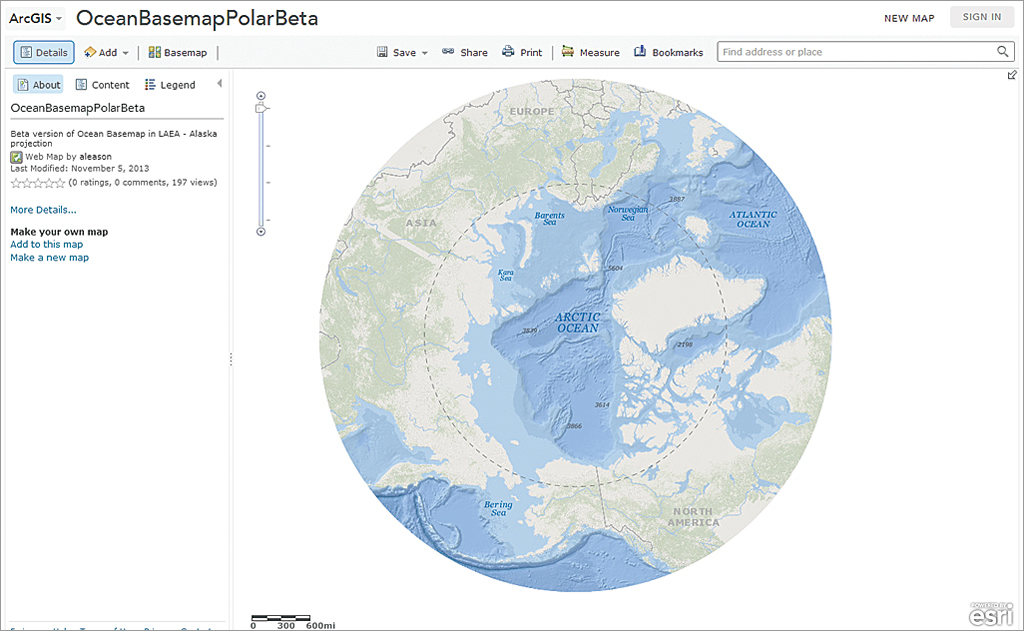

Caitlyn Raines, Esri project manager for database services, announced some structural changes to the Ocean Basemap that was released last year. The new version, the New Ocean Basemap—Beta Version, covers 36 million square miles in high resolution and will comprise two feature services. The first feature service provides hydrographic and terrestrial cartography, and the second feature service contains reference information and labels. By allowing the reference layer to be turned off, this change provides more flexibility in using the basemap with other data. In addition, the NoData tiles will no longer display when the map is zoomed in beyond the resolution available in an area. Instead, the closest available resolution will be resampled. When the official updates are published on ArcGIS Online, the beta version will be removed, although the previous version of the Ocean Basemap will be supported until the end of 2014.

In addition to changes in the Ocean Basemap, Raines also announced the release of the Arctic Ocean Basemap—Beta. It will use a Lambert Azimuthal Equal Area projection centered over Alaska to allow the Arctic Ocean Basemap to interface seamlessly with other Esri software products.

The Journey Continues

With the feedback from this year’s conference, Esri will continue moving the Esri Oceans Initiative forward and developing the GIS tools and data that enable the ocean community to better understand and work in the complex marine environment. GIS can be especially valuable in capturing the public’s interest in the fate of the ocean by delivering scientific information as maps that make a compelling case for changing human behavior.

Moving from “what is”—limited knowledge of the ocean and abusive practices toward it—to a “what could be” future of greater understanding and widely held appreciation of the critical role of the ocean is a challenging goal. In his closing remarks, Esri ocean solutions manager Drew Stephens proposed enlisting the help of members of the ports community, offshore energy and shipping industries, and atmospheric research field who could provide additional information and insights. The situation is urgent, and the task is great. As Gallo noted, quoting Cameron, “The oceans are changing faster than we can understand them.”