In May 2015, the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) and Esri invited a small group of local government executives to Esri’s Redlands campus to participate in a white boarding exercise that would capture their ideas on how best to develop strategies for delivering services to citizens, fostering collaboration with other organizations, and measuring performance. This carefully selected group of professionals represented communities large and small from across the United States. White boarding exercises are informal events in a think tank-like setting where executives can learn about technology trends and discuss the needs of their organizations.

In recent years, executives have dealt with reduced budgets and staffing that is the legacy of the recent recession. In many cases, the sources and funds allocated to governments have shifted. Policy changes, new legislation, and changes in the tax base mean that resources are no longer sufficient to pursue large projects. In practical terms, this means many jurisdictions continue using legacy business systems with less than optimal workflows.

At the same time, they must deal with a growing list of issues, many related to an aging population and deteriorating infrastructure coupled with a citizenery that now expects additional social services for groups such as veterans and those with mental health needs. Citizens also expect those services to be conveniently accessible via the web and smartphones.

This had led many local governments to embrace a smart communities approach: using digital technologies to manage resources more effectively and engage citizens. GIS plays a pivotal role in enabling the transformation of a community of any size into a smart community.

Partnering with Communities

Over the last several years, ICMA and Esri have cohosted Executive White Boarding exercises as a way to better understand the challenges executives face and help Esri develop smart community solutions that address these needs. These exercises nominally focus on a specific topic. The most recent session zeroed in on health and human services, an area of growing concern for governments as the population ages.

However, government’s role in health and human services delivery can’t be neatly parsed from the other types of services governments furnish. Consequently, the initial discussion revolved around the much broader topic of how to communicate with citizens in a simple way and collaborate with other organizations. That sparked wide-ranging conversations that occupied the morning session.

The consensus was that phones, specifically smartphones, are the single best method to reach the people who need services but may not have traditional computer access or even a mailing address. According to the Pew Research Internet and American Life Project undertaken in 2014, 90 percent of all American adults own a cell phone, and of those, 58 percent have smartphones. These statistics span virtually all income levels. This reality has been acknowledged by some jurisdictions that give out basic phones to homeless people because it was found to be the only effective way to communicate with this population.

Beyond agreeing that apps are an effective mechanism for delivering information, several participants identified a fundamental problem governments have when communicating with citizens. Most local governments require citizens to understand government organizational structure to determine which department or agency can supply what they need. Michael Penny, the city manager of Littleton, Colorado, and a veteran of Esri White Boarding exercises summed the situation up by saying, “We did not design ourselves around apps.”

To be effective, public-facing apps should be user-centric in the manner of Yelp, Pinterest, and other popular consumer apps. Apps should be about what the citizen wants and not what is most expedient for goverment. “We don’t need to regurgitate the same information in yet another format,” said Penny.

John Salomone, the town manager for the Town of Newington, Connecticut, and Veronica Ferguson, an administrator for Sonoma County, California, also noted that—increasingly—the character of communication with the public is changing. Citizens, particularly younger ones, want a dialog with government, not just an answer. Technology is helping to change the nature of public meetings from the comments of a handful of citizens who showed up at city hall to an ongoing discussion online that can include input from many citizens. GIS applications such as GeoPlanner for ArcGIS can facilitate these kinds of interactions.

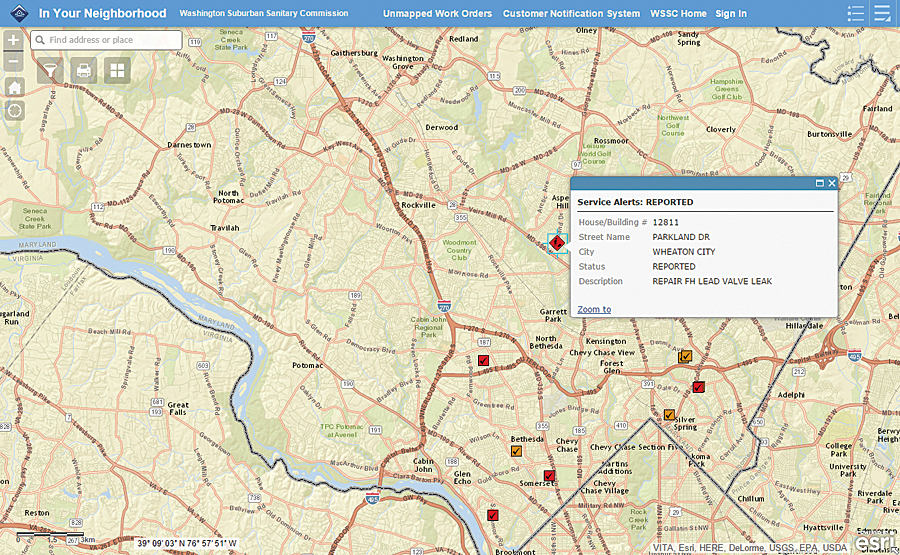

In fact, GIS is almost always an aspect of citizen-centric apps because information about the location of services is most useful when placed in a geographic context. People don’t always go to places in their own counties for services. They go to the nearest location for those services. Frequently, they don’t know or care about jurisdictional boundaries. They just want their needs met as quickly and simply as possible.

This jurisdictional indifference drives both collaboration and, by extension, interoperability. By working together, local governments, agencies, and nonprofits can provide better, cost-effective service by more intelligently locating service centers. Conversely, sharing data on community resources with nonprofits and other entities not only helps get information out to citizens but can also enhance other programs, efforts, and research and lead to collaboration.

However, unlocking data and forming partnerships can be challenging. As several participants noted, some open data solutions are far from user-friendly and “are basically for geeks.” Pushing data to the cloud primarily to eliminate local infrastructure requirements and reduce costs without any real plan for making it usable does not enable data sharing or app development with that data. From a developer standpoint, disparate cloud sources of data that have not been organized with openness in mind can be at best difficult to use and at worst nearly useless.

However, ArcGIS Online, with its online hosting, mapping capabilities, and apps and templates, facilitates data sharing without requiring a high level of technical expertise. ArcGIS Open Data, functionality built into ArcGIS Online, easily generates a website dedicated to sharing datasets selected from an existing ArcGIS Online or ArcGIS Server site and automatically updates those datasets, ensuring the most current data is used.

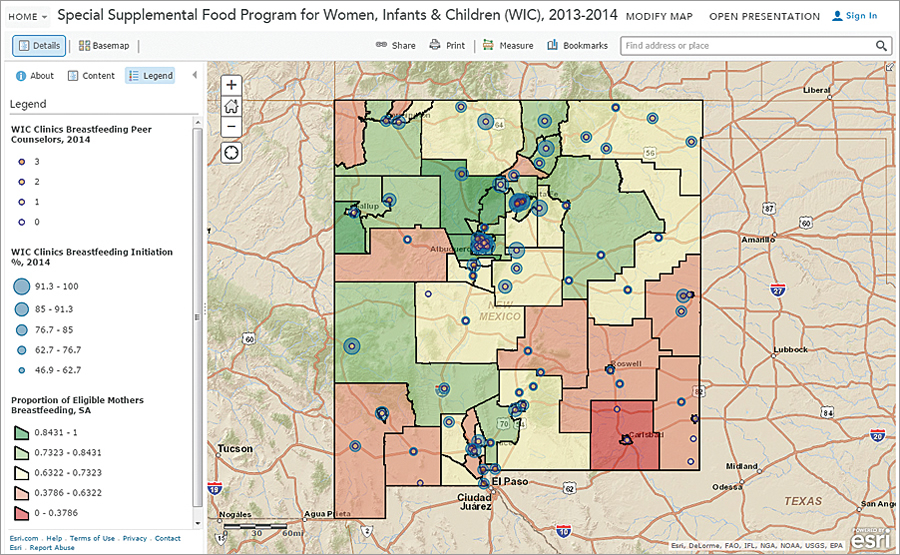

Esri director of government marketing Christopher Thomas, one of the event moderators, used the success of the New Mexico Community Data Collaborative (NMCDC) as an example of the value of data sharing using ArcGIS Online. This statewide data repository makes its health and human services data available through an ArcGIS Online site that was built entirely using free Esri apps. The site lives up to its motto, “Building community capacity to move data into action,” by making more than 200 neighborhood-level datasets with more than 1,200 variables available to other agencies, nonprofits, and researchers.

During its first few months of operation, there were 56,000 data downloads from the site. Instead of concentrating on developing health apps, NMCDC develops and shares the neighborhood-level data that makes it possible for other government agencies and universities to do research that promotes community assessment, child health, and participatory decision making.

In addition to supplying data, NMCDC will collaborate with and train users of its data warehouse, offering workshops, consultation services, and assistance to users without requiring payment. Collaborating analysts, who are subscribers to the site, can upload and store data, make maps and apps, use files shared by others, and copy and modify maps.

This example also encouraged continuation of a discussion of the characteristics of successful apps. Good apps should be self-service, relevant to the citizen, unconstrained by jurisdictional boundaries, and provide context so the information can be understood. Great apps should incorporate demographics and/or the user’s profile to provide information tailored to the individual that might even anticipate the user’s needs and support a virtual experience.

An Esri Story Map is a great tool for sharing information with citizens and other agencies, whether that information is the amenities available at local parks or the status of disaster response efforts.

Thomas said local governments often run into problems when they hire an outside app developer. These developers do not thoroughly understand the problem they are trying to address. They are not part of government and typically don’t understand the existing business processes or consider the needs of citizens.

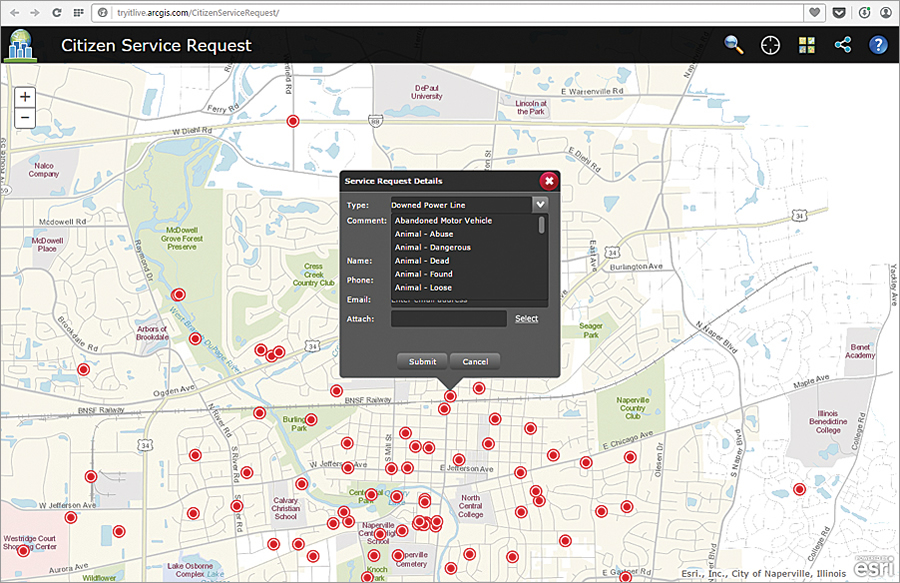

Esri has been extending the ArcGIS platform to bring app development within the grasp of local government without requiring hiring developers, either in-house or on contract. For several years, Esri has been developing solution templates that supply functionality needed for land records, water utilities, public works, fire services, emergency management, law enforcement, planning and development, and elections departments. More than 150 of these configurable apps—some the direct result of feedback obtained from white boarding sessions—are available at no charge from ArcGIS Online.

To provide greater customization, ArcGIS Online and Portal for ArcGIS now includes Web AppBuilder for ArcGIS. Using this what-you-see-is-what-you-get wizard environment, nonprogrammers can create custom web mapping applications that run on any device.

AppStudio for ArcGIS, currently in beta, is another tool that lets nonprogrammers create apps. It can convert maps into mobile apps for Android, iOS, Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux that run natively on smartphones, tablets, and desktops.

An App Wish List

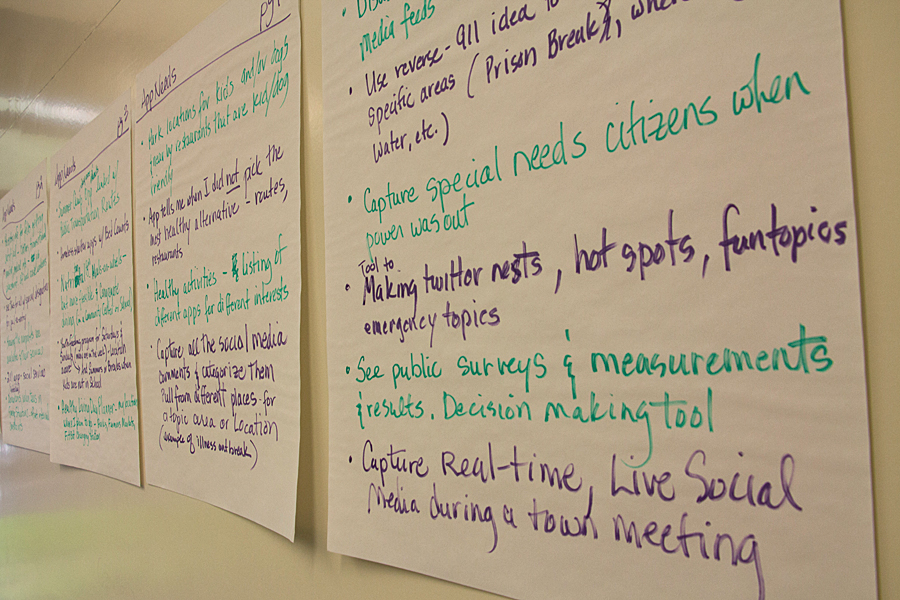

After lunch, the group engaged in a brainstorming session to identify apps that would improve the delivery of government services and internal government processes. A sampling of the long wish list of public-facing apps compiled during the session included apps that

- Provide captions for hearing disabled persons attending a city event.

- Locate nearby businesses that accept Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) cards.

- Apply the Uber model for sharing cars to provide transporation for seniors and disabled persons.

- Provide information on where to get clothes, transitional housing, and other necessities for people leaving jail.

- Locate all nonprofits in a community.

- Locate and describe nearby social services.

- Coordinate donations of clothing and food in response to a disaster.

- Show the real-time status of snowplows.

Internal apps were also listed. Most of these apps related to dealing with social media through aggregating feeds and mapping interest in specific topics to support officials when dealing with the public.

After creating the wish list, apps were prioritized and three high-priority apps were chosen: an app for capturing and aggregating social media comments, a 211 app for social services, and an app to measure the success of a job placement program. In the last exercise of the day, the group was divided into three teams and each was assigned a priority app. Each group identified the typical user for the app, the information it would provide, the information it would collect, how it would be used, and what would constitute a successful outcome.

Participants felt that walking through this robust app design process—which included not only who would use the app and how it would be used but also what information it would provide and how to determine if it was successful—was very valuable. They planned to share the insights they gained with others in their organizations and fellow ICMA members.

Intelligently built apps that promote smart community goals help executives make better informed decisions, departments accomplish more, and citizens remain engaged with local government.