Deep in the heart of Texas lies Texas A&M University (TAMU), known to generations of former students as Aggieland.

Founded in 1876, TAMU was the first public university in Texas and is now one of the largest research universities in the United States, with more than 58,000 students, including nearly 14,000 graduate students. It was one of the first US universities to hold the triple distinction of being a land-, sea-, and space-grant institution, meaning it does leading research in all three domains. Thus, it is prime breeding ground for GIS.

The Organic Growth of GIS

During the 1980s, GIS research developed organically across TAMU. Professors in several departments—including landscape architecture, entomology, parks and recreation, forest science, and geosciences—used the emerging technology to support their diverse research needs.

Due to the high costs of computers at the time, TAMU began GIS instruction in 1985 only in the forest science department after PhD student (and now associate professor) Douglas Wunneburger developed microGIS. This homegrown program ran on 20 Tandy 2000 personal computers in the university’s then state-of-the-art computer lab.

Interest in microGIS spread quickly. The College of Medicine used it, along with electron micrographs (digital images taken through an electron microscope), to calculate the density of whole viruses. The plant pathology department also employed microGIS to create spatial models for controlling oak wilt, a fungal disease that can kill oak trees quickly. Those models have since become standard practices.

Student interest escalated, too. By the end of the 1980s, the forest science department’s class, GIS for resource management, had expanded to six sections, reaching more than 100 students per semester.

At the same time, workstation costs decreased and Esri became the standard GIS software on campus. This gave the department of geography in the College of Geosciences the impetus to become TAMU’s second venue for GIS coursework, even motivating the geography faculty to construct its own GIS laboratory.

From its inception, GIS instruction in the geography department focused on the underlying philosophy and theory of GIS rather than just keyboarding. Before long, GIS instruction in the geography department began to nurture research, and masters and doctoral students started submitting theses and dissertations in which GIS played key roles.

In 1994, the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences opened the Mapping Sciences Laboratory (MSL). This was an important milestone for GIS research at TAMU, as it expanded the university’s capabilities in GIS, remote sensing, and GPS navigation. Resident scientists were initially from the department of forest science, though scientists and students across campus used the laboratory. Scientists from the Center for Infrastructure Engineering later joined the facility. Campus GIS projects managed by the administrative GIS team under the Planning and Institutional Research Office also contributed to the strong cohort of GIS specialists housed in the lab. In fact, the combination of talents from each of these groups gave rise to a significant body of knowledge that, to this day, still tackles mapping science problems on campus and around the world.

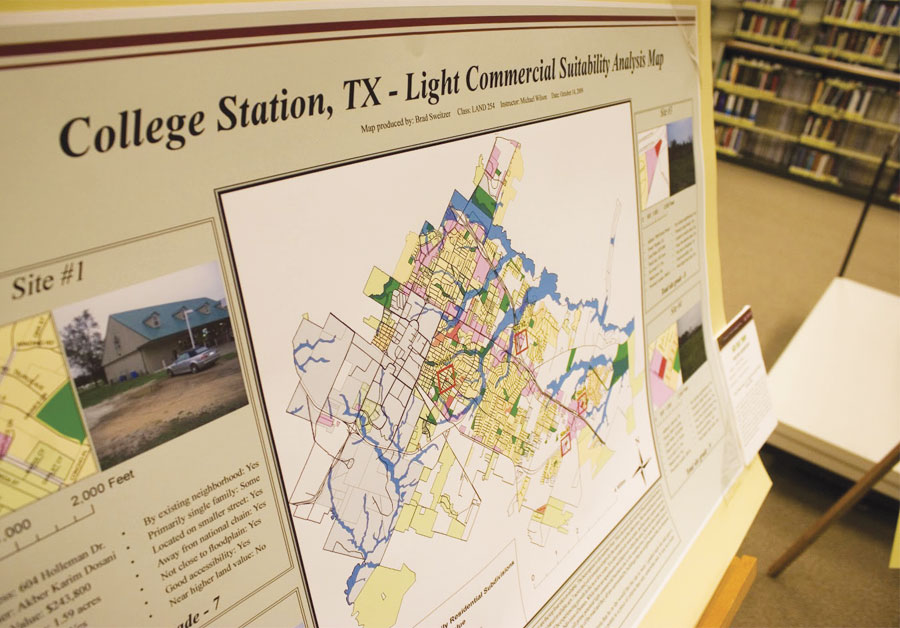

Finally, because of needs in landscape architecture, urban planning, architecture, and construction science, the College of Architecture became the third school to teach GIS in 1998. Based in the department of landscape architecture and urban planning, the GIS program has evolved greatly from “eight computers running off of a single extension cord,” as Wunneburger put it, to a lab that houses several research centers that allow students to collaborate with groups throughout the university, such as the Texas A&M Transportation Institute.

Three Decades of GIS-Based Facilities Management

At the same time that GIS research and instruction progressed at TAMU, the technology’s use in campus administration burgeoned, too.

As one of the nation’s largest universities, sprawling over 5,200 acres (21 square kilometers), GIS has been an important tool for managing TAMU’s infrastructure for almost three decades. In 1988, committees within the division of finance and administration met to discuss developing a campus GIS. Around the same time, TAMU joined a multi-agency partnership with the Texas Department of Transportation to take aerial photography of the main campus and its outlying properties. This enabled the university to digitize information on campus infrastructure and create computer-aided design (CAD) drawings of university buildings.

These initial projects have since evolved greatly, and facilities organizations continue to use GIS heavily today. Transportation services, for example, uses GIS to create specialized event maps, route buses, and help residents and visitors traverse campus and safely park. GIS is also critical for planning and communicating updates about various construction projects.

“GIS has…brought better information into decision making and in the campus master planning process,” said Jim Culver, assistant director of the office of facilities coordination. “At A&M, GIS has grown from an entity entirely unto itself to a tool used by many people across campus.”

Now, GIS Instruction for the Thousands

From its humble beginnings, GIS at TAMU has grown to support research in virtually every college and agency at the university.

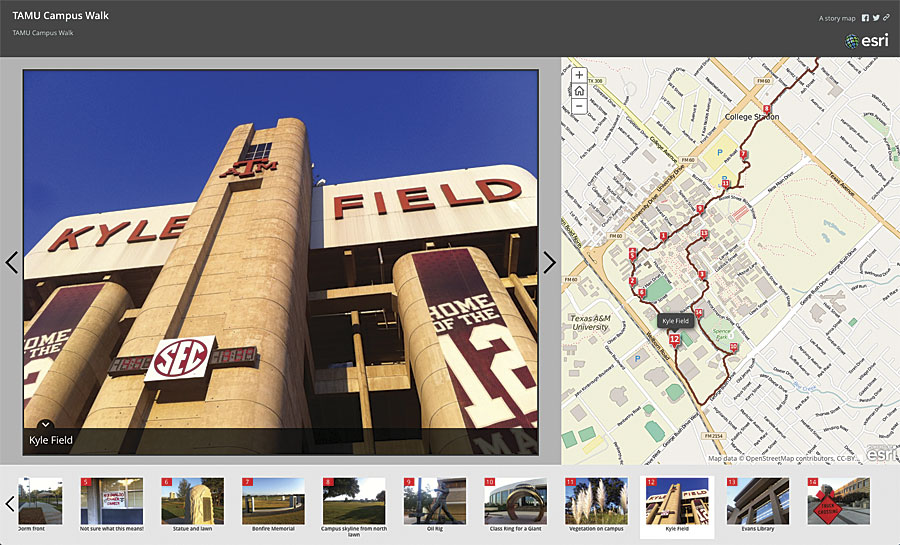

Eight departments now instruct thousands of students each semester in courses ranging from introductory GIS to highly specialized graduate classes. Students can select GIS-centric majors in three different colleges, leading them into a diverse choice of careers in fields that include natural resources, agriculture, urban planning, geodesign, oil and natural gas, and national security, to name a few. The university has a full-time GIS librarian who provides GIS research assistance and outreach and does data curation for the libraries’ large collection of local, state, national, and international data. TAMU has also been designated an Esri Development Center, which enables students to build software that extends the functionality of Esri products.

The university is also home to numerous federally and state-funded academic research centers that focus on using and developing GIS to solve wide-ranging social challenges. The College of Architecture contains the Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center and the Center for Housing and Urban Development, which focus on research and building applications for general and disaster planning. The Texas Research Data Center in the College of Liberal Arts conducts census research that serves the south-central region of the United States and is one of only eight secure census research facilities at US universities. The Dwight Look College of Engineering hosts the Center for Autonomous Vehicles and Sensor Systems, which houses one of six authorized drone test sites in the country. And the Texas A&M GeoInnovation Service Center in the College of Geosciences provides research and commercially applicable geoprocessing and data collection solutions for various industries; nonprofits; and local, state, and federal agencies.

A Bright Future for GIS

TAMU’s GIS enterprise reflects two of the university’s defining traits: its decentralized administration model and its friendliness.

Because of TAMU’s large size, individual colleges have a lot of independence. So GIS is also dispersed. But the numerous GIS entities across campus have long been friendly with one another, with faculty and staff recognizing contributions from educators and researchers around the school.

This sense of respect drove the TAMU GIS community to establish the Center for Geospatial Sciences, Applications, and Technology (GeoSAT) in 2014. Its core mission is to foster multidisciplinary collaboration among faculty, researchers, and students to advance geospatial knowledge and provide practical solutions for the development and use of geospatial technology in the realm of economic development.

GIS will continue to be carefully and innovatively cultivated at Aggieland, just as it has been for the past three decades. Here, the technology faces a bright future.

About the Authors

Daniel W. Goldberg is an assistant professor of geography in the departments of geography and computer science and engineering. Andrew G. Klein is a professor in the department of geography. Douglas Wunneburger is an instructional associate professor in the department of landscape architecture and urban planning. John R. (Rick) Giardino is a professor in the geology and geophysics department. Sierra Laddusaw is the maps and GIS library supervisor. Eric Irwin is a GIS specialist for the university’s transportation services. David M. Cairns is head of the department of geography.