case study

Wasatch Front Regional Council Accelerates Change with a GIS Approach

The Wasatch Front Regional Council is using GIS to support transportation planning and economic development across the Salt Lake–Ogden metro area in northern Utah.

Hive of Activity

Transportation planners in Utah, the fastest-growing state in the US, have to find ways to meet the demands of a population predicted to grow by just over half again by 2050. At the same time, economic growth, powered in part by dozens of tech start-up companies on the "Silicon Slopes" just south of Salt Lake City, will increase by a factor of 10 the numbers of vehicles passing through some existing traffic congestion choke points.

Deciding the "what" and "where" of land use—residential, commercial, retail, and social—and the transportation networks necessary to service these future developments, is driving the comprehensive planning process, which currently looks out through the year 2050. In support of this plan, the Wasatch Front Regional Council (WFRC), which serves as the Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) for the greater Salt Lake City area, has developed a series of online applications designed to help planners and the public better understand the future demographic and economic growth in the region, and the transportation infrastructure required to maintain regional mobility. The Wasatch Front Regional Council shares these applications with the neighboring Mountainland MPO (Provo-Orem), and together they cover approximately two million people—roughly 75–80 percent of the Utah population.

The applications (https://maps.wfrc.org/) are based on Esri's geographic information system (GIS) technology and have a number of aims. These include easy access to the data for internal planning staff, better communication with relevant stakeholders, and the ability to invite and incorporate comments and interaction from the public. A key outcome is that everyone shares the same baseline of information to help drive consensus around these longer-range growth issues.

Zone by Zone, Link by Link

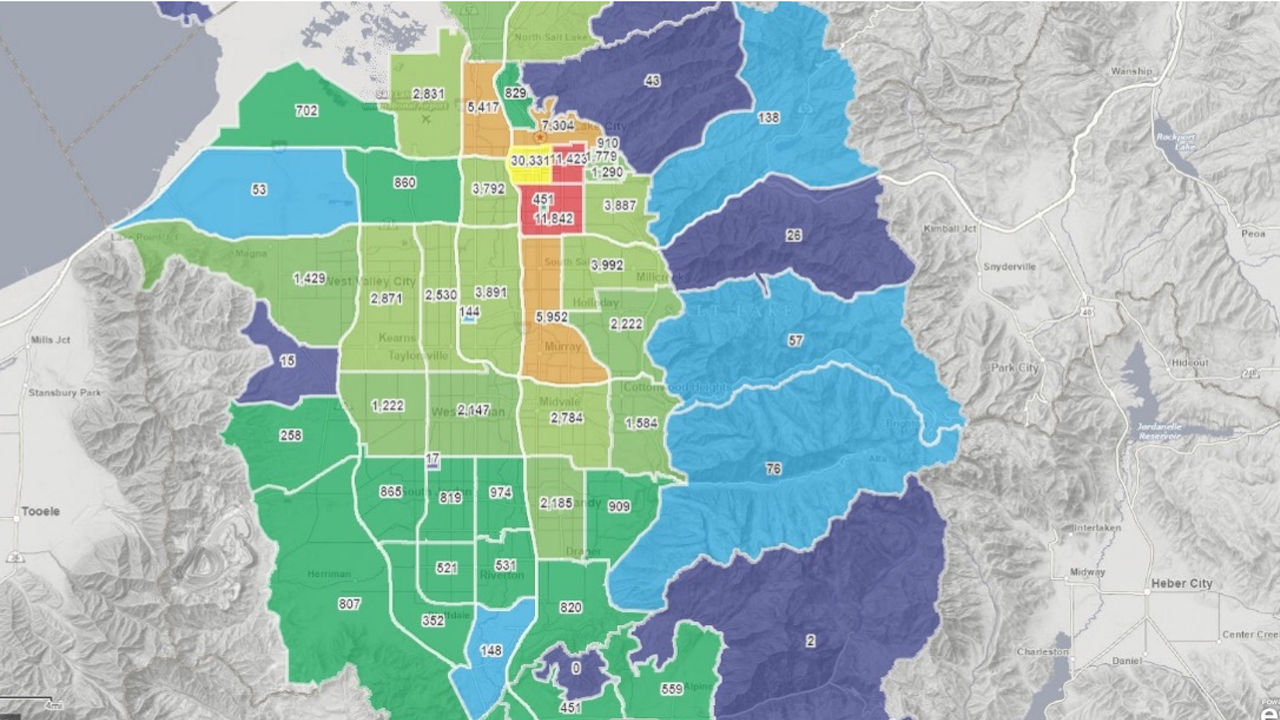

The applications present a wide variety of data at the Transportation Analysis Zone (TAZ) and individual road link levels.

Examples from a very comprehensive set include the following:

The Statewide Average Annual Daily Travel Map is the most popular. This enables users to see by year the traffic volumes down to the individual road segment level. They can also see traffic volume increases, as well as projected volume drops when completed projects displace travel on nearby roads. An advanced version of this map shows population and employment forecasts and planned projects by individual TAZ and aggregated across TAZs. It is also possible to view project stages by different transportation modes.

The Traffic Congestion Forecast Map uses volume-to-capacity ratios to show forecasted changes on road segments. Users can look at no-build, needs-based, and financially constrained scenarios. Time periods from three hours down to a peak of 15 minutes can be viewed, and all of the estimation and projections are informed by observed real-world data from the Utah Department of Transportation's (DOT) continuous vehicle count stations.

The Household and Job Forecast Viewer shows numbers of households, jobs, and job types (industrial, retail, and office) for each TAZ. Information can be combined to show these socioeconomic projections all the way out to 2050 for each TAZ or scaled to the district, city, or county levels. An advanced version shows the percentage of overall growth contributed by individual TAZs.

The Access to Opportunities Map shows, for each TAZ, the numbers of households and jobs reachable within typical auto or transit commute times in the region. Existing and future conditions as well as net gains can be viewed, as can 10-minute travel times from each specific TAZ.

The Residential Destination Accessibility Map enables users to select a community, choose from a range of destinations, and set priority weightings for each type of amenity. Access to jobs, transit, freeways, and community necessities, such as childcare/health care and groceries, can be seen and ranked. Selected criteria can also be grouped together—for example, transit and schools.

The Origin/Destination Map uses licensed location-based services data (aka big data) to convey travel connections made across the Wasatch Front urban region. Users can click individual districts and see the percentages of vehicles traveling to others. Data can be seen in time segments ranging from the annual down to individual times of day, filtered for specific seasons and months.

Easily Digestible

WFRC's web maps are designed to make complex data much more understandable. As Bill Hereth, a travel demand modeler and application developer with WFRC, explains:

"For each TAZ, our models look at variables such as population, employment, and other characteristics. They project where people will travel and assign [this] data to the roadways and networks. It's a complex environment—for example, our Traffic Volume app includes 3,000 different roadway segments, all the way up from collector roads to freeways—and outside of our travel demand modeling group, it's hard to really understand what's going on without these maps."

"The applications bring everything together in a more digestible format that's easier for all stakeholders to understand—previously, one barrier to accessing and using the data was that many people don't have GIS. Now, the information we produce can reach anyone with a browser."

Use Cases

Out in the community, potential users of the applications vary widely. Hereth gives the hypothetical example of a city council member in Cottonwood Heights who might want to establish a bus link between her community and the University of Utah.

"The origin-destination data in our StreetLight application shows how many people travel between very specific areas. The council member can zoom to her community, click on different areas, and see how many travelers there are, and where they go. Previously, to get that information, she'd have had to come to us with a specific question. We'd then have had to do the calculations and respond. Now, she can bypass us and get her answers more quickly and directly.

"This heightened information access extends to businesses as well as individuals. I have a neighbor who works for a billboard company. He can look at the numbers and types of vehicles on a particular road and use the information to set price points that will maximize revenue."

The ultimate goal of creating and sharing information via the applications, he continues, is to make things happen.

"We're simply not aware of all the potential external use cases, but for sure, these web maps help us internally. The long-range planning process involves quite a large group of people, but the supporting information often existed in silos. With these applications, we've opened those up—so, in our board meetings and other policy-making venues, staff now have the information they need at their fingertips. That makes providing good information straightforward, and getting decisions made, far easier."

That all happens even though more departments and agencies are involved.

"For example, we have a Bike Safe application. Active transportation is very much a hot topic at the moment, and our state governor has just announced an effort to connect all communities with paved routes. We coordinate with other agencies to get all bike facilities into one dataset. That's not just the on-the-road and grade-separated routes; it's all the off-road trails, too. And, at the same time, our Housing Transit Reinvestment Zone map enables communities to plan and lobby for cycling-related facilities around railway stations. The better coordination of all of this information has been very well received."

Better Engagement

The applications, which have now been available to the wider community for around three years, have been transformational in terms of the levels of stakeholder and public engagement.

"Our older communities are typically built on a gridded road network, while our newer ones are more suburban," Hereth continues. "We're trying to promote more connected streets, and, via our Regional Transportation Plan application, people can go in and submit comments. We'll receive over a thousand project-specific comments for our upcoming RTP.

"It's the same with the Household and Job Forecast map—we used to send stuff out to the cities and get next to little back, whereas now they can provide very specific feedback on our forecast within the maps. Many cities went TAZ by TAZ to review and submit comments."

The Household Planning app, by contrast, is mainly sent to a select list of community planning staff. Hereth notes that allowing for community-established priorities for this group is important, and the app easily facilitates that prioritization. Additionally, the app enables users to produce maps that can be included in other planning documents, such as housing elements of their community general plans.

Positive Attitudes

Appreciating that distinction between professional and nonprofessional users is important. Although it is now possible to more speedily communicate greater amounts of more accurate information to technical staff, without a significant training effort, the majority of the public would struggle to appreciate the applications' full capabilities.

This, however, does not mean that the public cannot appreciate their effects.

"Again, I'd come back to that ability to readily share information in public meetings," says Hereth.

"We removed some of the opacity of the transportation planning process, and the problem of poor attendance at public forums. In a way, we've democratized the planning model. That helps on so many levels.

"For instance, here in Utah, we have a travel pinch point at the confluence of two valleys. Salt Lake City sits in one valley, and the city of Lehi sits at the entrance to the other. Rapid tech industry development in the Silicon Slopes areas has left many residents very concerned about traffic levels. The timing of projects is also an issue; some of the development is preceding completion of necessary road projects.

"Some people don't want the development projects—the disruption, the change—but once you show them in meetings how the current 80,000 vehicle trips will increase tenfold by 2050 without mitigation, they start to say, 'Okay, how can we work to solve this?'

"If you don't understand the data, you often feel a victim to it. If you do understand it, then it enables you to be in a solution mindset."

Accelerating Change

GIS and the possibilities it opens up are transforming how things are done. These applications are now attracting transportation engineers, whose primary focus is often the Highway Capacity Manual, into a new and different world of information-sharing, Hereth feels.

"We now have big data and so many new technologies and information sources; on-demand transportation data from new and emerging platforms provides far greater insights into how people actually travel. So, instead of just responding to people's queries, there is a greater ability to pool knowledge and contextualize it. That, in turn, creates a wider range of possible solutions.

"The young professionals are coming into this space from school and easily plug into this more data-rich setting. The 'spreadsheet generation' produced some very good results, but it was a more siloed environment. The accessibility and ease of use of GIS-based applications is encouraging a more dynamic mindset and the speed of change in our field is increasing.

"At the same time, those same websites and apps are enabling the educated layperson to almost do their own transportation planning. The public's expectations are shifting, and they're better positioned to contribute to the process."