case study

Mapping the Road to Efficient and Transparent Transportation Planning

Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT) is bringing greater efficiency, transparency, and accessibility to its capital investment planning process, using geographic information system (GIS) technology.

RIDOT is responsible for maintaining a surface transportation system composed of more than 1,000 bridges and nearly 3,000 lane miles of roadway. When the Rhode Island Division of Statewide Planning (RIDSP) began the process of drafting a 10-year plan in 2019, RIDOT and its partners faced some significant challenges. The State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) needed an update, and so did the technology that supported it.

Previously, solicitation for projects was largely paper based, resulting in considerable duplication of data entry. The process was further compounded by not having common naming conventions, geographic extents, or data models, resulting in costly and inefficient planning processes with the potential to create additional challenges in design and construction.

To address these issues, the division redesigned the project application and prioritization process to incorporate GIS, standardizing data and information management right from the start.

This approach has completely digitized the project planning process, consolidating all project information into a single GIS environment. It has transformed RIDOT's ability to anticipate project conflicts, design more efficient projects, generate cost savings, and improve transparency with a public-facing dashboard.

Bundling projects together electronically within off-the-shelf tools has already brought about greater efficiencies, and with a few final additions, it will evolve into the State-Wide Intake Framework for Transportation (SWIFT).

The Decision to Put Mapping First

When work began on the new STIP, RIDOT placed a high priority on creating a system to manage the planning process. "When we started to rewrite our 10-year plan, we decided to start with mapping and let everything else follow. That's a reversal of what had been happening for years,"explains Steve Kut, GIS data analyst at RIDOT. "It involved stepping back and thinking about how we develop projects, manage data, and deliver it in a useful way for multiple recipients. In the old days, we put project information into an Access spreadsheet and left the GIS guys to figure out what was happening and where. We ended up trying to paint a picture in GIS that was never finished or [made to look] as it should. So we said, 'Let's paint this from scratch in GIS.'"

The team placed a priority on efficiency and accessibility. Data needed to be delivered in a way that was useful for both expert staff members and external stakeholders seeing it for the first time. "What's cool about that is the clarity and efficiency of how projects can be communicated, and it enables more people to be able to step in and do that, as it reduces our work burden," Kut adds.

Vincent Flood, a data analyst with RIDSP (the metropolitan planning organization for the state), highlighted the benefits of that decision. "Now, there's a great opportunity for towns, cities, and the public to be more informed and invested in the STIP application process and in developing the STIP digitally—work that, 10 years ago, was largely paper based," he says. "Esri's GIS technology has been of great use in making the whole process more user-friendly."

Figure 1. RIDOT's STIP Programming Bundler, the COTS Tool Used to Develop the State's 10-Year Plan

Figure 1. RIDOT's STIP Programming Bundler, the COTS Tool Used to Develop the State's 10-Year Plan

New and Improved Processes

Rhode Island's first 10-year plan was completed in 2017 and covered fiscal years 2018–2027. Local stakeholders submitted project applications on paper; the projects were evaluated, and RIDSP entered them into a local database. Only then were they mapped. This resulted in significant issues with data duplication, consistency, and integrity.

"There are lots of problems with that old process. One is redundancy. Another is that, because mapping was the last step, conflicts and inefficiencies were figured out only after everything was already committed," explains Ken White, assistant director for administrative services in RIDSP. "We wanted to avoid a situation where folks would say, 'I'm repaving this road right now, but in less than a year, you're going to be rebuilding the bridge underneath it.'"

A lengthy STIP amendment requiring some $400 million in savings to be realized in 2019 underlined the need for an improved methodology. The team at RIDOT reevaluated its entire process and settled on the idea of a GIS-based program.

"As we moved to the new STIP, we sat down and asked, 'What's this thing going to look like?' One goal was to make the whole process more asset driven," says White. "We turned to bridges as an example case because our bridge team had a really good data model in place already. Also, we execute bridge contracts as groups—we'll pick several bridges close to each other with similar needs and put them out as one contract. We wanted to follow that example for the other asset types that we have to manage. Pavement is the largest one, plus safety systems, ITS [information technology services], stormwater management and facilities—everything that the state has to manage that has a locational footprint."

COTS Solution

The GIS-first approach has done much to address the opacity (and occasional contradictions) of the initial project review process, and significantly improved statewide interdepartmental communications. Rhode Island has done so by using standard solutions. "We started with a simple data model while using off-the-shelf Esri products within the web portal. [We] built around assets as the foundation for all projects, [used] project polygons to show projects' physical boundaries, and [created] a project information table.That three-part structure became the basis for everything we did," says Kut.

"We built an application, the STIP [Programming] Bundler, to capture all of the project information. Within the Bundler, we've mapped all the different projects we have. We've built in quite a lot of functionality, but the basic premise was to have people use a batch editor to select assets and assign a common STIP [project] ID. That creates the building blocks for projects which eventually wind up in the public dashboard."

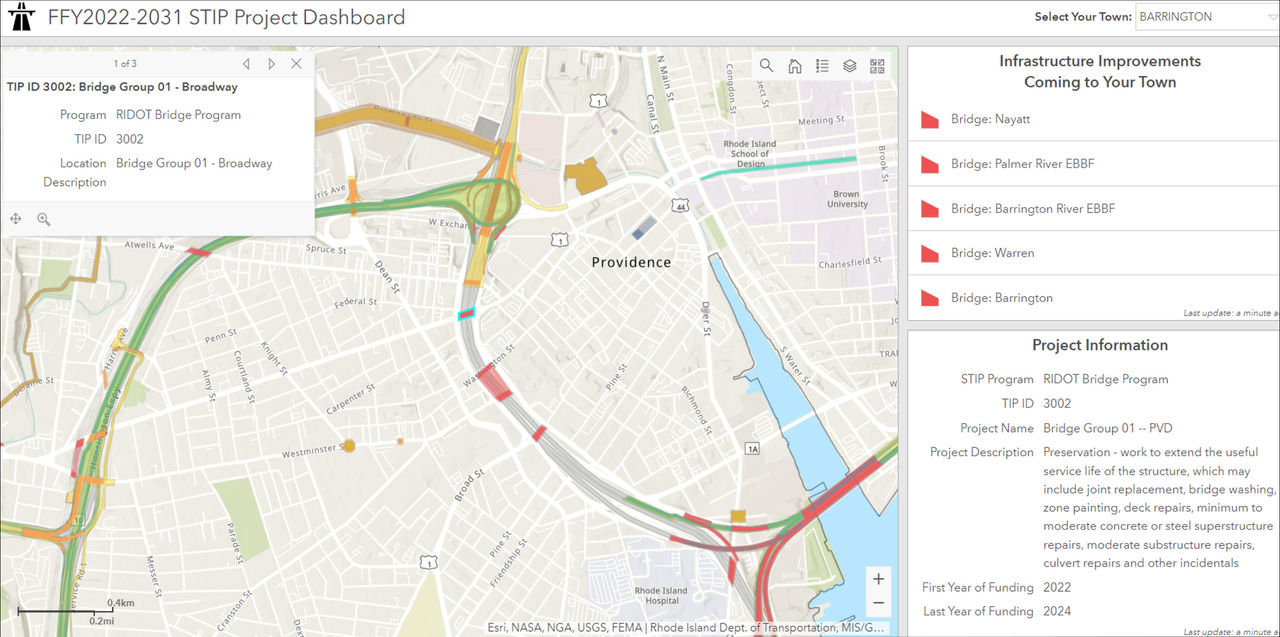

The dashboard was a popular and powerful tool throughout the STIP adoption process, and it's easy to see why. "Folks can come in; pull up their town; select different segments of road or bridges; and find out which project they're in, when it'll be executed, how much funding it has, et cetera," says Kut.

White emphasizes the power of off-the-shelf tools: "One thing that we really struggled with is what we affectionately call 'fire drills,' where we might have a tight deadline to answer, for example, how many miles of sidewalk we've replaced in a municipality in the last eight years. A few years ago, that was almost impossible to answer. It's still a difficult question, but at least we can now say, 'Here's what we're planning to do in the next 10 years,' and it's all mapped. I can give linear feet, total area, and estimated cost. I can even provide a map of exactly where everything's going to be. You can call everything up and run through each segment individually, all things that just weren't possible even three years ago."

Standards

"The most obvious thing that this has done is to force asset classes, other than bridge, to start to be classified in the same way," White states.

"It's given us a more authoritative data source for everything that we're planning on doing, in a format that's also accessible to us. We can work with the information in the GIS," he says. "And because it has a SQL back end, we can just extract information back out if we need to manipulate it in, say, a spreadsheet. We don't need to have an export file or do a special search for individual things, because the GIS tools can give us either a spatial query and let us look at the outputs, or just give us everything from the back end and let us do the slicing and dicing that we need. So it's given a lot of structure where really there was very little."

One of the biggest benefits RIDOT staff have realized is the ability to visually spot opportunities to combine projects, saving time and expense down the line.

Rhode Island's efforts to build the STIP Programming Bundler application have saved RIDOT countless staff hours by minimizing manual data input and eliminating redundancies. Time is saved on the planning side, resulting in cost savings on the project delivery side, all while using commercial off-the-shelf tools.

"There was very little customization other than using tools that Esri provides and building those into the workflow. We did some integration, using ETL [extract, transform, and load] tools to push data back and forth," says Kut.

"We always knew that we were going to move towards a more structured approach to capture project information," he continues. "Now, we're working on the things that we couldn't build [with COTS products], and bringing together the lessons learned over the last couple of years."

SWIFT

"The initial concept for SWIFT was that we needed something that's going to digitize project intake and somewhere we can send communities and outside stakeholders who want us to review something," says White.

While successful, a limitation of the STIP Programming Bundler was accessibility for external people looking to add new projects—it essentially externalized an internal process, failing to provide a sandbox to build potential projects that were not designed well. SWIFT will enable residents to identify a local area where they want changes, see the state of existing assets, and then apply for funding. Crucially, it will enable several different workflows to come together. SWIFT will support three unique, interconnected functions: processing applications for new projects; scoring, evaluating, and prioritizing those applications; and, finally, combining projects into bundles to achieve economies of scale and push a finished product out for public review.

SWIFT will also add a next level of dynamic capability. As projects evolve, there will be the ability to understand the implications of suggested changes very quickly.

"In short order," explains White, "we will be able to run some geoprocessing to see what the effects will be—are we in a historical area, for instance, or have we bled into a coastal area that requires additional permitting? With each project, we get to a geoprocessing step where we run the project parameters against a series of considerations that have permitting and readiness implications."

White continues, "On the one hand, it's about prioritizing projects [and] presenting things in a transparent way for the public. On the other, in three years' time when this project is going to a design consultant, we'll already know in advance we have a handful of things to worry about. It's every stage of the planning process in one application."

The RIDOT development team spent a lot of time looking at roles and responsibilities to ensure that each user and agency has the right permissions and duties.

All users will be able to contextualize information that would not be apparent without the advances in mapping tools developed over the last three years.

Social Setting

This development work has already proved valuable to RIDOT, particularly for stakeholder and public engagement and improved customer service. White reflects on these impacts: "The dashboard was a huge, huge benefit when we put the 10-year plan out for public comment. We actually received comments from people saying things like, 'This is really cool—I like that I can just see where my projects are.' It's had 6,000 views in a year, which is pretty significant."

For Rhode Island, GIS is now a cornerstone of a complete e-STIP to manage the future of transportation planning in the state. "Once we get to the point we're ready to launch SWIFT, that's going to add another group to the digital project pipeline even earlier in the process: our local stakeholders and counterparts," adds White. "And the best part is, all the work we do together will be entered into the same application from the very start."