case study

Center of the Storm

Port NOLA's new EOC will use GIS to increase weather awareness and maintain safe operations.

As the Port of New Orleans (Port NOLA) entered into the 2022 hurricane season, it did so with a new geographic information system (GIS)-based Emergency Operations Center (EOC) coming online.

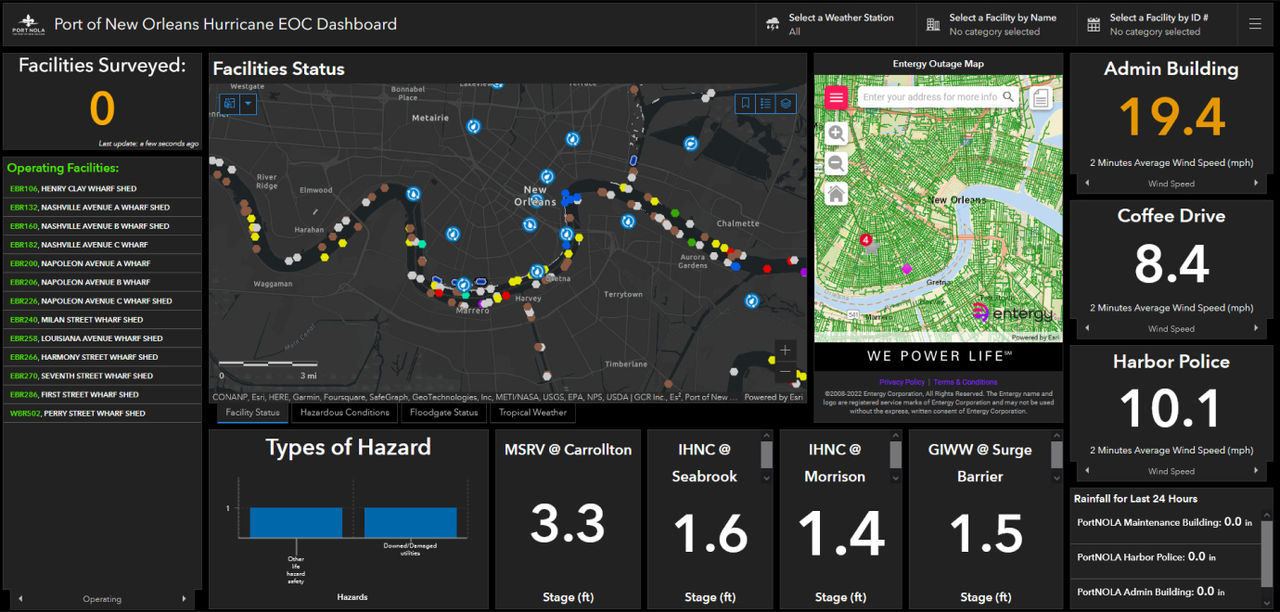

Intended to facilitate the protection of life, safety, and property during severe weather events and to resume operations as soon as possible, the EOC will see staff responsible for emergency management sheltering in place and continuing to operate. It uses ArcGIS GeoEvent Server to drive a series of dashboards, which facilitate real-time decision-making.

The work to create the center extends as far back as 2015, but it was 2021's Hurricane Ida—a Category 4 storm—that provided the biggest catalyst for the EOC's realization. In particular, says Port NOLA's GIS manager Maggie Cloos, the extended difficulties caused by mass power outages as a result of Ida underlined the need for better communication and information dissemination.

"The biggest use case for us is hurricane related. Our hurricane season lasts for half the year, but we also have to cope with lots of severe thunderstorms and, very occasionally, tornadoes," she says.

Deepwater Asset

Port NOLA is a multimodal cargo gateway and is Louisiana's only international container facility. It is also a year-round passenger cruise port. With seven active marine terminals, Port NOLA generates $100 million in revenue annually through its four lines of business: cargo (46 percent), rail (31 percent), cruise lines (16 percent), and industrial real estate (7 percent). With recent investments in the Napoleon Avenue Container Terminal, total annual capacity is one million TEU. The port handles principally containerized cargo such as plastic resins, food products, and consumer merchandise, as well as break-bulk cargo such as steel and nonferrous metals, rubber, wood, and paper. A second two million TEU container terminal is expected to open its first berth in 2028.

A number of unusual features drove many of the decisions relating to the creation of the EOC. Port NOLA sits below sea level and features a series of floodgates in the $14.5 billion federal flood protection system that was rebuilt after Hurricane Katrina. Since 2018, Port NOLA has also been aligned with the New Orleans Public Belt Railroad. This is a short-line railroad that serves the port and industry, providing switching and haulage services between local customers and the six Class I railroads that converge in New Orleans.

The port authority itself does not operate the terminals or carry out the cargo-handling function.

"Our operations are geared around being a landlord," explains Cloos. "We're lean staffed but have a lot of real estate set across three parishes, and a large number of different stakeholders."

Scaling into Real Time

Monitoring at-sea conditions and vessel movements is the responsibility of the US Coast Guard. Within the port, GeoEvent Server is used in conjunction with data from on-site, regional, and national monitoring assets to trigger alerts and actions when weather conditions hit certain thresholds. Locomotives need to be behind floodgates before they are closed, and gantry crane operations have to be curtailed or the cranes parked and secured as wind speeds increase. In addition, local businesses on the flood side need to be able to make timely decisions on evacuating staff and key assets.

Previously, stakeholder communication relating to extreme weather events was primarily telephone and email driven. This process had obvious limitations. Port NOLA has 70 industrial clients in addition to partner agencies such as flood protection authorities and multiple first- and second-responder organizations. With this sheer number of stakeholders, it makes for a complex environment.

"It's exciting to be moving to more hands-on and dynamic emergency management. The ability to give people a common operating picture with the same metrics in terms of actual weather and other on-the-ground conditions in and around port facilities is going to be transformative," Cloos states.

Developing the Solution

The initial scoping exercise for the EOC extended over two years, and Cloos describes stakeholder involvement as one of the major successes of the process. The scoping looked at what was needed locally and also harvested information about what other ports were doing. Given that location was central to much of what was being planned, GIS was a natural choice, and Esri assisted to stand up the enterprise environment.

Ahead of going live, Port NOLA followed an agile development approach, with five separate iterations for its real-time environment. Each iteration refined the look of the dashboard concept, as well as the data collected. The emphasis, in line with the requests of those stakeholders responsible for emergency management, was on a pared-down range of fields, giving only essential information.

This is still using a production system, according to Cloos. For further development of some of the applications desired in the future, a development environment that will allow more advanced configuration within GeoEvent Server will likely be needed. Nevertheless, she describes moving into the cloud as "Version 2.0," and she already sees several advantages.

"Having a dedicated technical team has been great for us. Being able to leverage the cloud will deliver great benefits and help us be more resilient and less susceptible to power disruptions outside our control. This will be a real game changer," says Cloos.

In prior hurricane seasons, Port NOLA utilized a dashboard solution to monitor data from the National Hurricane Center, which was combined with radar data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and local information such as river/canal levels and floodgate statuses.

The new system that was developed built upon that base and was able to demonstrate significant improvements through the use of the EOC dashboard. This was illustrated, according to Cloos, by the floodgate status reporting. The gates are coded using a two-letter/one number identifier. Before the dashboard, closures were communicated on a list via email, which gave no concept of geography. Placing that information on a map enables immediate identification of location and the tenants and stakeholders affected.

Access

Dashboard access will be restricted to essential personnel only. "We've given staff designations as to whether they're essential or needed in person. There's a subset that has access that is involved in planning, receiving briefings, and making decisions," Cloos says.

"Some information is sensitive and will remain restricted. An example is locomotive locations. Other information may be shared on a case-by-case basis. Floodgate closure status, for example, could be shared, as that would mean not having to rely on lots and lots of emails."

Field Apps

There are two field apps that feed into the EOC. The first provides a basic postevent "windshield" survey capability, documenting whether buildings have sustained damage or are without power. The second will map hazardous conditions and is for use by Harbor Police Department (HPD) officers and maintenance teams who need to respond to damage. This monitors flooding, debris, and down/damaged utilities.

"This is used to keep our first responders safe but also to share information with other responding agencies," explains Cloos. "For example, our on-site firefighting capability is limited to a fire boat, so we coordinate with the New Orleans Fire Department to respond to terminal incidents.

"We also coordinate with the New Orleans Police Department for the less restricted areas of our real estate—all of our maritime terminals are highly secure with very tightly controlled access, but much of our industrial real estate is simply fenced and publicly accessible. We would also coordinate with Louisiana State Police if there were a hazmat spillage."

A third field app, which sits outside the EOC proper, is being developed for the HPD. This will enable officers to report back in real time to a smaller set of key individuals with executive power in the case of emergencies.

Extending Capabilities

Much of the emergency management/preparedness work centers on building resilience and redundancy into workflows. Using pre- and post-Hurricane Ida as a benchmark, Port NOLA has been considering how to maintain information flows. If decision-makers no longer have cellular coverage, for instance, they may still be able to get online via nomadic devices and access dashboard information.

In addition, Cloos is looking ahead to "Version 3.0" of Port NOLA Maps and the incorporation of added functionality. This would include information provided by the terminal operators about the volumes of cargo being handled on-site or the numbers of vehicles entering their facilities. These data items can also influence emergency management, notes Cloos, by providing temporal decision points on allowing vehicular access.

Meanwhile, adding GPS devices to cranes' booms would result in the ability to track their movements in real time. This would be an additional step in providing the operators with warnings of predicted straight-line wind speeds on wharves and enable operations to be continued for as long as possible.

"I'd also really like closer coordination with HPD's operations," says Cloos. "They're in the process of choosing their next generation dispatch system, and it'd be great to make sure we can integrate further in the future and have better visibility of what they're doing in terms of responding to incidents.

"There's a lot of cool stuff we can expand into, but we're still at the pilot stage. Once we've proven the EOC's and GIS's efficacy, then hopefully we'll see buy-in and be able to really expand," adds Cloos. Given the frequency of hurricanes in the gulf, there will be plenty of opportunities to prove the value of the Port of NOLA's investment.