User Story

Exploring Infertility Insurance Mandates with Qualitative GIS

Key Takeaways

• Nate Stanley, who graduated with a PhD in public health from the University of South Florida in 2020, used quantitative spatial analysis and qualitative methods in his dissertation to study the impact of state-mandated infertility insurance on access to infertility services in the United States.

• Stanley used GIS software to analyze how infertility clinics clustered in the United States. He combined this spatial analysis with surveys and interviews to understand people’s accessibility to infertility treatment from both a location and policy perspective.

• By combining quantitative and qualitative methods, Stanley gained valuable insights into the challenges many endure while accessing infertility services.

• The product featured in this story was ArcGIS Pro.

For aspiring parents in the United States, navigating the complex landscape of infertility services—medical interventions to help conceive, including medications, surgeries, and advanced techniques like in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intrauterine insemination (IUI)—can be daunting. Insurance coverage for these services varies state by state, with some state governments requiring private insurers to cover some specific diagnostic services or treatments, while other states have no requirement to cover any type of infertility service. Some mandates include exclusions for religious groups and employers with less than 50 employees, allowing them to opt out of including infertility insurance coverage, further restricting access.

"Infertility affects many, but access to those treatments is uneven," said Nate Stanley, who earned his doctorate from the University of South Florida College of Public Health. Stanley, now an applied research scientist at Moffitt Cancer Center, continues his interest in policies on infertility services through involvement with Fertility Within Reach, a nationwide advocacy group that aims to increase access to fertility treatment and fertility preservation through policy advocacy. So far, they have supported 29 pieces of legislation in 20 states contributing towards increased access to fertility services and support for fertility healthcare.

Stanley, particularly interested in "the role of policy and politics on individuals' bodies," tackled the topic of infertility treatment access in his doctoral dissertation by leveraging his background in anthropology and GIS expertise. His research used both quantitative and qualitative methods to study how state infertility insurance mandates and clinic locations affect access to infertility treatments.

Contextualizing Infertility Treatment Challenges with Qualitative GIS

During his doctoral coursework at the University of South Florida, Stanley studied literature on health outcomes of births from infertility treatments. He focused on issues such as chronic illnesses and early mortality occurring in births from assisted reproductive technology (ART), finding some research pointed to the effect of maternal and paternal stress on ART birth outcomes, and how stress is passed down through generations, having a biological impact on children. It was during those studies that he discovered just how stressful it was for those individuals and couples to initially find and access infertility services, especially since the costs were high and insurance coverage was rare. Stanley's studies inspired him to focus his dissertation on exploring the legal stressor—the policies and insurance coverage for infertility services.

"Theoretically, the states with infertility [insurance] mandates have better access, but in practice the benefits of those mandates really aren't uniformly felt across populations and that discrepancy raises some important questions about the effectiveness of those policies," said Stanley.

There is no universal coverage across the nation, resulting in each state being able to create policies that may have exclusionary clauses. These clauses could create more obstacles for individuals trying to access certain services. For example, some limit coverage to only in vitro fertilization, exclude surrogacy, or only allow married heterosexual couples to benefit.

"This is a state-specific type of thing, so to tackle those discrepancies and those questions of whether a mandate worked for someone or why it didn't, I wanted to make spatial data out of this qualitative inquiry," said Stanley.

Qualitative data interpretation varies between GIS professionals and other researchers, impacting their analysis methods. GIS experts typically convert non-numerical data such as surveys into numerical formats that include geographic context. In contrast, sociologists and anthropologists often work with data from interviews, photos, and observations. Stanley stresses it was vital to integrate quantitative spatial analysis with qualitative methods to fully grasp the complexities of accessing infertility treatment. "You really need that next level of context [that comes from] a mixed-method design," explained Stanley.

At the time of Stanley’s research, much of the existing research on the topic focused on insurance claims data, comparing states with mandates to those without. However, these analyses often overlooked critical factors happening at the individual level, such as the outcomes of treatments, the number of treatments received, the use of a surrogate, or the necessity for patients to travel for treatment. Some people have even been willing to relocate to gain access to necessary treatment, Stanley said.

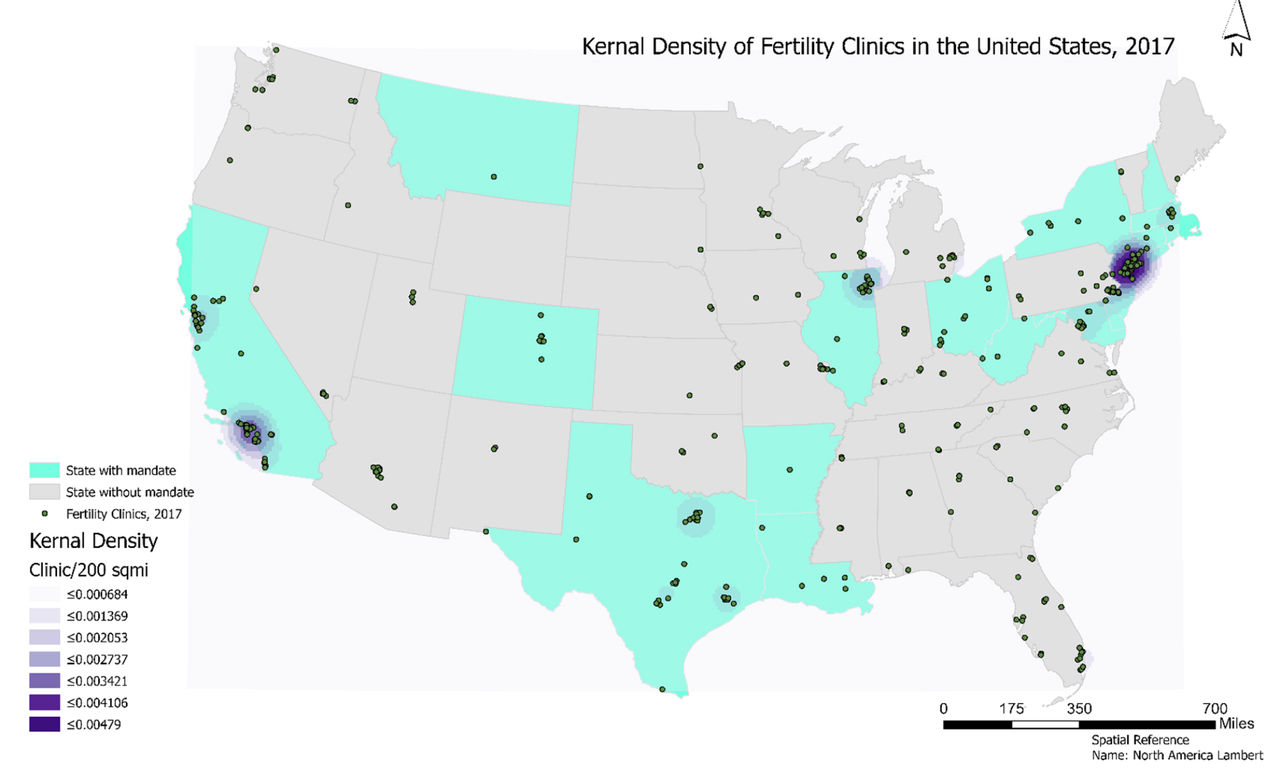

Stanley's mixed-methods approach allowed him to incorporate previously overlooked factors into his analysis, such as the role of location in accessibility to infertility treatment. Utilizing ArcGIS Pro, he analyzed the distribution of infertility clinics across the United States using a density analysis. The density analysis was compared to population density, and also compared between states with and without infertility insurance mandates. This analysis showed a national view of density of infertility clinics and identified areas with a shortage of clinics. To further support his investigation, Stanley conducted 134 surveys, 66 informal interviews, and eight expert interviews (organizations providing educational/financial assistance for infertility services). By using spatial data as the basis for his research and cross-referencing his qualitative findings with the spatial analyses, Stanley could draw more nuanced correlations that tied together the story of access to infertility services in states with and without an infertility insurance mandate.

To do so, he turned to Reddit, discovering an engaged infertility community. Aware that many Reddit boards have strict rules about conducting research, he worked closely with the moderators to get approval for his study. To his surprise, the moderators of the larger threads were very supportive of his research efforts. “They were like, 'finally somebody is looking [at this]’.”

The survey shared on Reddit explored a range of questions, asking participants if they lived in a state with an insurance coverage mandate, whether they had traveled for treatment, and how their insurance affected their access. Participants were also invited to indicate their interest in a follow-up interview. About 66 percent of those surveyed agreed to be interviewed, with an even split between those in states with insurance mandates and those without. "It was incredible. I couldn’t have planned for that, but it really helped the analysis and comparisons for those experiences because I had an almost even number of people telling me these things.”

Kernal density analysis using a defined search radius of 200 miles revealed some high-density clusters of ART clinics in metropolitan areas, such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago. This image indicates whether a state did or did not have an infertility mandate in 2020 based on the state's infertility insurance mandate status at the time.

Kernal density analysis using a defined search radius of 200 miles revealed some high-density clusters of ART clinics in metropolitan areas, such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago. This image indicates whether a state did or did not have an infertility mandate in 2020 based on the state's infertility insurance mandate status at the time.

Findings Shed Light on Infertility Treatment Access and Methodology Success

Stanley said using both quantitative and qualitative methods gave him key insights into access to infertility services—insights he couldn't have gained from using just one approach.

“You can ask spatial questions, or you can ask questions that you would want to confirm through a spatial analysis,” said Stanley. “Importantly, you can ask the questions that your spatial analysis can’t answer, too, especially with personal stories.”

For example, the spatial density analysis in ArcGIS Pro revealed that infertility clinics mainly cluster in urban areas across the country. Stanley’s density analysis supported the personal accounts he heard: most individuals could get to a fertility clinic because most people lived in or near a large urban area. But spatial access was different than financial access, and the lack of financial access led some people to travel long distances to find greater financial access.

Interviews revealed that a state’s infertility insurance coverage, if it existed, significantly influenced a person’s financial access to infertility treatments, and financial access influenced the spatial access of a fertility clinic. "If I had just done the cluster analysis and not had a qualitative component, I would have interpreted the results maybe a lot differently," said Stanley, adding that this method allowed him to look at all the dimensions surrounding access and without bias.

As a result of his efforts, Stanley advocates for a creative approach to social science research. He believes that integrating quantitative GIS data with qualitative data can yield deeper insights and more effective solutions, especially when tackling public health challenges.

“Having this framework that intrinsically connects all of these data points together and forces you to look at them as a whole, I think, makes it easier to find a tangible solution,” said Stanley.

Apply ArcGIS to Social Science

Read case studies and resources about how GIS tools can support mixed-methods research