In the last post, I said we face four key challenges as we look to make strategic transportation investments. The first part of an investment strategy must focus on our core transportation systems and how rebuilding our core transportation infrastructure can be a critical component in the recovery from the current recession. Economic activity during this pandemic has fallen even more precipitously than it did in the crash of 1929. So there will be a strong need to recover lost jobs and rebuild the workforce, which has never fully recovered from the great recession of 2008. With interest rates at all-time lows, we should use the opportunity to rebuild our basic transportation infrastructure—roads, bridges, ports, airports, and rail systems—to provide the multimodal networks to support the supply chains of the future.

America’s transportation networks are really the connective tissue that physically unites the country, and they are central to the success of our economy. They serve to facilitate the movement of materials and manufactured products, moving roughly 55 million tons of goods—worth just under $50 billion—every day. And the magnitude of that trade is expected to grow considerably in the future, with freight volume increasing 62 percent by 2040, and the value of that freight increasing 134 percent during the same period.

We have already documented the decline in infrastructure spending in the US, and indeed, much of America’s transportation infrastructure is old, overburdened, and underserviced due to years of neglect and inadequate funding. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) released its 2017 report card for US infrastructure and assigned the country’s transportation networks an overall letter grade of D+. The ASCE estimated that the nation would need to invest $4.9 trillion over the next decade to restore infrastructure to relative health (a B+ grade)—up from $3.6 trillion in 2013, the year of ASCE’s previous report card. And if the infrastructure funding gap is not swiftly addressed, the US could suffer $7 trillion in lost business sales by 2025 and 2.5 million lost jobs.

Of the major roadways in the US, ASCE estimates that 32 percent are in poor or mediocre condition, costing every driver an estimated $324 a year in additional repair and operating costs. And it is not just poor roadways that are the problem: Americans lost an average of 97 hours a year due to congestion, costing them nearly $87 billion in 2018, an average of $1,348 per driver (https://inrix.com/press-releases/scorecard-2018-us/). For the trucking industry, the costs of congestion are equally staggering: nearly $50 billion annually. That’s equivalent to 264,500 truck drivers sitting still for an entire year.

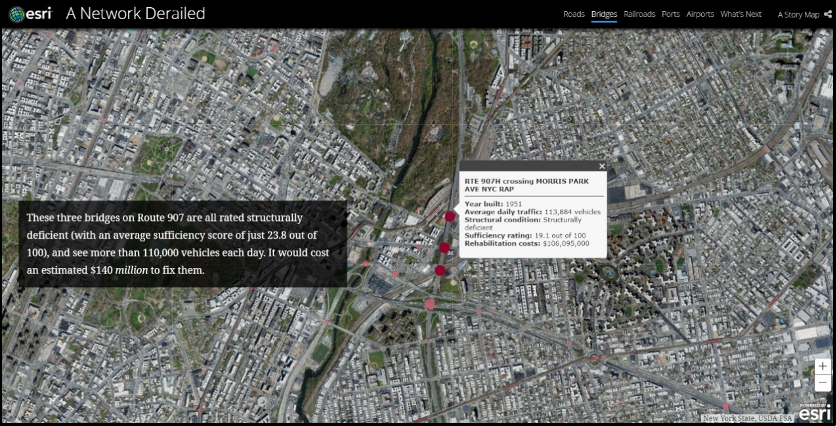

Bridges came out only slightly better, with an overall grade of C+. That said, almost 4 in 10 are 50 years of age or older, the expected life-span of most structures. The problem at heart is that the bulk of federal transportation funding relies on the Highway Trust Fund and is based on a fixed-rate gas tax, which has not been updated since 1993. The tax is not indexed to inflation, so it has lost 40 percent of its purchasing power over the last 24 years. Consequently, the fund has teetered on the brink of insolvency for many years.

The same level of underinvestment carries over to our ports; airports; public transit; and, to a lesser extent, rail, since many of our rail networks are privately owned. So we have the opportunity to reinvest and to rebuild our multimodal transportation networks but with greater integration and greater rationality from a goods movement and supply chain perspective. Because of the state-by-state development pattern of much of our infrastructure, there are gaps and inefficiencies in our current networks that could be fixed, and with the right type of expertise and national investment, we could create much more efficient and competitive transportation networks to serve a global economic market. Improvements to our intermodal infrastructure can pay big dividends. The inadequate connections from port terminals to the surrounding roads and rail lines is one of the biggest challenges, causing delays when moving goods from ports to market (and vice versa), as just one example. Better inland intermodal facilities could help us better leverage our vast rail networks, relieving congestion on the roads and reducing freight costs, thus keeping prices down.

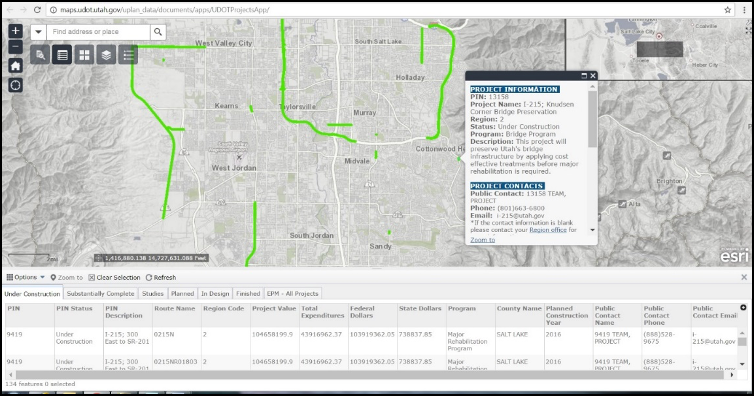

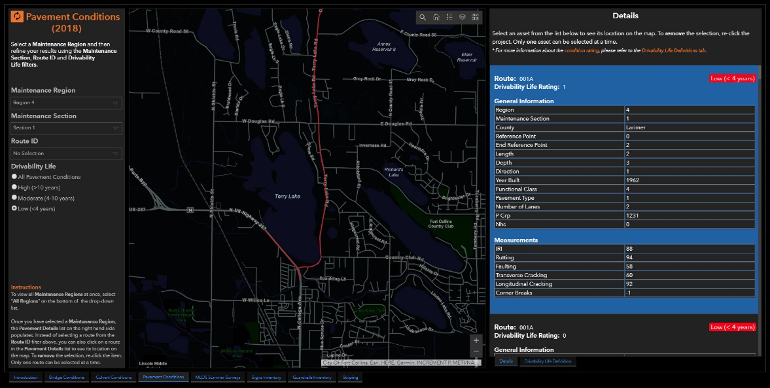

A final point: effectively addressing America’s infrastructure needs begins with knowing where to make the most strategic investments. And that is where geographic information system (GIS) technology and location intelligence can play an important role in helping us understand the condition of our infrastructure, where the largest bottlenecks occur, and where dollars should be targeted to make the greatest impact on the nation’s economy. Expert modeling combined with the analytic capabilities of GIS can tell us where the most strategic investments should be made and can facilitate the necessary collaboration between Congress, the US Department of Transportation (DOT), and the states to ensure that we are building the infrastructure of the future and not replicating the networks of the past. And with a bold investment plan, this would create a large number of well-paying jobs to help speed the economic recovery.